Equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the planetary orbit. This planetary concept allowed Ptolemy to keep the theory of uniform circular motion alive by stating that the path of heavenly bodies was uniform around one point and circular around another point.

Ptolemy does not have a word for the equant – he used expressions such as "the eccentre producing the mean motion".[1]

Placement

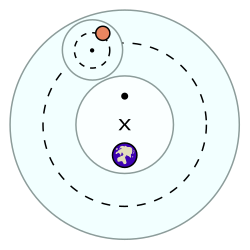

[edit]The equant point (shown in the diagram by the large • ), is placed so that it is directly opposite to Earth from the deferent's center, known as the eccentric (represented by the × ). A planet or the center of an epicycle (a smaller circle carrying the planet) was conceived to move at a constant angular speed with respect to the equant. To a hypothetical observer placed at the equant point, the epicycle's center (indicated by the small · ) would appear to move at a steady angular speed. However, the epicycle's center will not move at a constant speed along its deferent.[2]

Motivation

[edit]The reason for the implementation of the equant was to maintain a semblance of constant circular motion of celestial bodies, a long-standing article of faith originated by Aristotle for philosophical reasons, while also allowing for the best match of the computations of the observed movements of the bodies, particularly in the size of the apparent retrograde motion of all Solar System bodies except the Sun and the Moon.

The equant model has a body in motion on a circular path not centered on the Earth. The moving object's speed will vary during its orbit around the outer circle (dashed line), faster in the bottom half and slower in the top half, but the motion is considered uniform because the planet goes through equal angles in equal times from the perspective of the equant point. The angular speed of the object is non-uniform when viewed from any other point within the orbit.

Applied without an epicycle (as for the Sun), using an equant allows for the angular speed to be correct at perigee and apogee, with a ratio of (where is the orbital eccentricity). But compared with the Keplerian orbit, the equant method causes the body to spend too little time far from the Earth and too much close to the Earth. For example, when the eccentric anomaly is π/2, the Keplerian model says that an amount of time of will have elapsed since perigee (where the period is , see Kepler equation), whereas the equant model gives which is a little more. Furthermore, the true anomaly at this point, according to the equant model, will be only whereas in the Keplerian model it is which is more. However, for small eccentricity the error is very small, being asymptotic to the eccentricity to the third power.

Equation

[edit]The angle α whose vertex is at the center of the deferent, and whose sides intersect the planet and the equant, respectively, is a function of time t as follows:

where Ω is the constant angular speed seen from the equant which is situated at a distance E when the radius of the deferent is R.[3]

Discovery and use

[edit]Ptolemy introduced the equant in "Almagest".[4] The evidence that the equant was a required adjustment to Aristotelian physics relied on observations made by himself and a certain "Theon" (perhaps, Theon of Smyrna).[2]

Hipparchus

[edit]In models of planetary motion that precede Ptolemy, generally attributed to Hipparchus, the eccentric and epicycles were already a feature. The Roman writer Pliny in the 1st century CE, who apparently had access to writings of late Greek astronomers, and not being an astronomer himself, still correctly identified the lines of apsides for the five known planets and where they pointed in the zodiac.[5] Such data requires the concept of eccentric centers of motion.

Before around the year 430 BCE, Meton and Euktemon of Athens observed differences in the lengths of the seasons.[2] This can be observed in the lengths of seasons, given by equinoxes and solstices that indicate when the Sun traveled 90 degrees along its path. Though others tried, Hipparchos calculated and presented the most exact lengths of seasons around 130 BCE.

According to these calculations, Spring lasted about 94+1/ 2 days, Summer about 92+1/ 2 , Fall about 88+1/ 8 , and Winter about 90+1/ 8 , showing that seasons did indeed have differences in lengths. This was later used as evidence for the zodiacal inequality, or the appearance of the Sun to move at a rate that is not constant, with some parts of its orbit including it moving faster or slower. The Sun's annual motion as understood by Greek astronomy up to this point did not account for this, as it assumed the Sun had a perfectly circular orbit that was centered around the Earth that it traveled around at a constant speed. According to the astronomer Hipparchos, moving the center of the Sun's path slightly away from Earth would satisfy the observed motion of the Sun rather painlessly, thus making the Sun's orbit eccentric.[2]

Most of what we know about Hipparchus comes to us through citations of his works by Ptolemy.[4] Hipparchus' models' features explained differences in the length of the seasons on Earth (known as the "first anomaly"), and the appearance of retrograde motion in the planets (known as the "second anomaly"). But Hipparchus was unable to make the predictions about the location and duration of retrograde motions of the planets match observations; he could match location, or he could match duration, but not both simultaneously.[6]

Ptolemy

[edit]Between Hipparchus's model and Ptolemy's there was an intermediate model that was proposed to account for the motion of planets in general based on the observed motion of Mars. In this model, the deferent had a center that was also the equant, that could be moved along the deferent's line of symmetry in order to match to a planet's retrograde motion. This model, however, still did not align with the actual motion of planets, as noted by Hipparchos. This was true specifically regarding the actual spacing and widths of retrograde arcs, which could be seen later according to Ptolemy's model and compared.[2]

Ptolemy himself rectified this contradiction by introducing the equant in his writing[4] when he separated it from the center of the deferent, making both it and the deferent's center their own distinct parts of the model and making the deferent's center stationary throughout the motion of a planet.[2] The location was determined by the deferent and epicycle, while the duration was determined by uniform motion around the equant. He did this without much explanation or justification for how he arrived at the point of its creation, deciding only to present it formally and concisely with proofs as with any scientific publication. Even in his later works where he recognized the lack of explanation, he made no effort to explain further.[2]

Ptolemy's model of astronomy was used as a technical method that could answer questions regarding astrology and predicting planets positions for almost 1,500 years, even though the equant and eccentric were regarded by many later astronomers as violations of pure Aristotelian physics which presumed all motion to be centered on the Earth. It has been reported that Ptolemy's model of the cosmos was so popular and revolutionary, in fact, that it is usually very difficult to find any details of previously used models, except from writings by Ptolemy himself.[2]

From Copernicus to Kepler

[edit]For many centuries rectifying these violations was a preoccupation among scholars, culminating in the solutions of Ibn al-Shatir and Copernicus. Ptolemy's predictions, which required constant review and corrections by concerned scholars over those centuries, culminated in the observations of Tycho Brahe at Uraniborg.

It was not until Johannes Kepler published his Astronomia Nova, based on the data he and Tycho collected at Uraniborg, that Ptolemy's model of the heavens was entirely supplanted by a new geometrical model.[7][8]

Critics

[edit]The equant solved the last major problem of accounting for the anomalistic motion of the planets but was believed by some to compromise the principles of the ancient Greek philosophers, namely uniform circular motion about the Earth.[9] The uniformity was generally assumed to be observed from the center of the deferent, and since that happens at only one point, only non-uniform motion is observed from any other point. Ptolemy displaced the observation point from the center of the deferent to the equant point. This can be seen as violating the axiom of uniform circular motion.

Noted critics of the equant include the Persian astronomer Nasir al-Din Tusi who developed the Tusi couple as an alternative explanation,[10] and Nicolaus Copernicus, whose alternative was a new pair of small epicycles for each deferent. Dislike of the equant was a major motivation for Copernicus to construct his heliocentric system.[11][12]

The violation of uniform circular motion around the center of the deferent bothered many thinkers, especially Copernicus, who mentions the equant as a "monstrous construction" in De Revolutionibus. Copernicus' displacement of the Earth from the center of the cosmos obviated the primary need for Ptolemy's epicycles: It explained retrograde movement as an effect of perspective, due to the relative motion of the earth and the planets. However, it did not explain non-uniform motion of the Sun and Moon, whose relative motions Copernicus did not change (even though he did recast the Sun orbiting the Earth as the Earth orbiting the Sun, the two are geometrically equivalent). Moving the center of planetary motion from the Earth to the Sun did not remove the need for something to explain the non-uniform motion of the Sun, for which Copernicus substituted two (or several) smaller epicycles instead of an equant.

See also

[edit]- Equidimensional: This is a synonym for equant when it is used as an adjective.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ Claudius Ptolemy. The Almagest (PDF). Translated by G.J. Toomer.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Evans, James (April 18, 1984). "On the function and probable origin of Ptolemy's equant" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 52 (12): 1080–89. Bibcode:1984AmJPh..52.1080E. doi:10.1119/1.13764. Retrieved August 29, 2014.

- ^ See equation 8 in "Eccentrics, deferents, epicycles and equants". Mathpages. The quthor derives this in a complicated way using derivatives and integrals, but in fact it follows directly from equation 3.

- ^ a b c Ptolemy, Claudius. Μαθηματικὴ Σύνταξις (Mathēmatikē Syntaxis) [Mathematical Treatise ("Almagest")]. IX, 5.

- ^ Gaius Plinius Secundus. "An account of the world and the elements: Why the same stars appear at some times more lofty and some times more near". Naturalis Historia [Natural History]. Book 2, Chapter 13. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ Equants, from Part 1 of Kepler's Astronomia Nova. The New Astronomy. science.larouchepac.com. Retrieved 1 August 2014. — An excellent video on the effects of the equant

- ^ Perryman, Michael (2012-09-17). "History of Astrometry". European Physical Journal H. 37 (5): 745–792. arXiv:1209.3563. Bibcode:2012EPJH...37..745P. doi:10.1140/epjh/e2012-30039-4. S2CID 119111979.

- ^ Bracco, C.; Provost, J.-P. (24 July 2009). "Had the planet Mars not existed: Kepler's equant model and its physical consequences". European Journal of Physics. 30 (5): 1085–1092. arXiv:0906.0484. Bibcode:2009EJPh...30.1085B. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/30/5/015. S2CID 46989038.

- ^ Van Helden. "Ptolemaic System". Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ^ Craig G. Fraser (2006). The Cosmos: A Historical Perspective. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-313-33218-0.

- ^ Kuhn, Thomas (1957). The Copernican Revolution. Harvard University Press. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-674-17103-9. (copyright renewed 1985)

- ^ Koestler, A. (1959). The Sleepwalkers: A history of man's changing vision of the universe. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. p. 322; see also p. 206 and refs there. "The Sleepwalkers" (archived copy) – via The Internet Archive (archive.org).

External links

[edit]- Ptolemaic System – at Rice University's Galileo Project

- Java simulation of the Ptolemaic System – at Paul Stoddard's Animated Virtual Planetarium, Northern Illinois University.