Carvetii

| Carvetii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Geography | |

| Capital | Clifton Dykes or Carlisle (Luguvalium) |

| Location | Cumbria North Lancashire |

| Rulers | Venutius? |

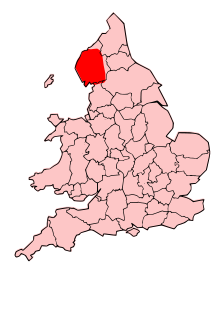

The Carvetii (Common Brittonic: *Carwetī) were a Brittonic Celtic tribe living in what is now Cumbria, in North-West England during the Iron Age, and were subsequently identified as a civitas (canton) of Roman Britain.

Etymology

[edit]The suffix carv- is related to Welsh carw, Breton karv and Irish carow ('deer'). Richard von Kienle has proposed the translation "those who belong to the deer".[1]

Location

[edit]Historical speculation has the Carvetii occupying the Solway Plain, the area immediately south of Hadrian's Wall, the Eden Valley, and possibly the Lune Valley.

The Setantii may have occupied North Lancashire and south Cumbria.[citation needed]

Evidence of existence

[edit]The Carvetii are not mentioned in Ptolemy's Geography, nor in any other classical text, and are known only from three Roman (third and fourth century AD) inscriptions, one of which is now lost. One was in Old Penrith, (the Voreda Roman fort) north of the present Penrith, on a tombstone. The others were on two milestones: one at Frenchfield (north of Brocavum), and the other at Langwathby in Cumbria, both also near Penrith.[2][3] Higham and Jones, in 1985, suggested that the combination of the first two inscriptions mentioned above "allows us to infer the existence of the 'civitas Carvetiorum', or canton of the Carvetii, and the existence of its own council or governing body."[4]

Capital or centre

[edit]The capital of the Carvetii is presumed to have been Luguvalium (Carlisle), the only walled town known in the region. Higham and Jones suggest, given the location of the inscriptions, and given that the best land in the area was nearby, and also given the existence of a large (7 acres, 3 ha.) enclosed settlement site a couple of miles south-east of Penrith in the Eden Valley, that Clifton Dykes was the "logical location for the 'caput Carvetiorum' " ('the centre of the Carvetii').[5] In other words, despite the later importance of Carlisle as the centre of activity once the Romans had invaded (and the likely place where tribal councils would take place), the Eden Valley "was the heartland of the area concerned."[4] The Brougham area, with its seeming importance in the cult of Belatucadrus, its strategic position in the Eden Valley with its route to the east across Stainmore, its nearby history as a meeting place with three henges, as well as with "the presumed pre-Roman tribal capital at Clifton Dykes",[6] may have been the settlement focus of the Carvetii, at least before the Roman military campaigns in the AD 70s. Indeed, this might account for the building of the Roman fort at Brocavum. Rivet and Smith suggest that the name 'Carvetii' may refer to the British word 'carvos', meaning 'deer' or 'stag', and that this could have associations with the horned god Belatucadrus mentioned above.[7]

The Roman fort at Stanwix, on the north side of the River Eden, was one component of what was to become Carlisle. The other seems to have been a major settlement of people south of the river, with an Agricolan fort (A.D.78-79), re-built in the second century, roughly where the present Carlisle Castle now is. A stone fort was built on the site around 200 A.D. The excavations in the Blackfriars and Lanes areas indicate a substantial vicus, or civilian settlement, associated with the several stages of this fort.[8]

Links with the Brigantes and Venutius

[edit]The Carvetii may have been part of the neighbouring Brigantes confederation, and some, including Higham and Jones, have speculated that Venutius, first husband of the Brigantian queen Cartimandua and later (69 A.D.) an important British resistance leader in the 1st century, may have been a Carvetian. The series of marching camps set up by the Roman governor Quintus Petillius Cerialis, in his campaign in the early 70s, stretched away from Stanwick, across the Stainmore Pass towards the Eden Valley, suggesting that the Carvetii were the "centre of Venutius' power base and the prime objective of the ... campaigns".[6]

Ross, however, challenges these assumptions. She argues that the very notion of 'tribe', in the sense of a geographically-defined unit, probably did not exist in the north; that there is no evidence either of the Brigantes holding power over the northern 'tribes', or of a Brigantian 'confederacy' of tribes;[9] that there is no certain interpretation of the three inscriptions;[10] that there is no written evidence of Venutius being of the Carvetii; and that the archaeological evidence and the persistence of the name 'Luguvalos' at what was to become 'Carlisle', may point to the Carvetii being a pro-Roman tribe based in the Solway Plain with a centre at Carlisle, while Venutius may have led an anti-Roman, non-Carvetiian, tribe elsewhere, probably in the upper-Eden valley south of Penrith.[11]

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Sergent 1991, p. 11.

- ^ Ross 2012, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Edwards & Shotter 2005, pp. 79–87.

- ^ a b Higham & Jones 1985, p. 9.

- ^ Higham & Jones 1985, p. 10.

- ^ a b Higham & Jones 1985, p. 11.

- ^ Rivet & Smith 1979, p. 301.

- ^ Higham & Jones 1985, pp. 55–57.

- ^ Ross 2012, pp. 55–58.

- ^ Ross 2012, p. 59.

- ^ Ross 2012, p. 65.

Bibliography

[edit]- Edwards, B.J.N. & Shotter, David C.A. (2005). "Two Roman milestones from the Penrith area". Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society. 3. 5: 79–87. doi:10.5284/1064554.

- Higham, N.J. & Jones, G.D.B. (1985). The Carvetii. Peoples of Roman Britain. Stroud: Alan Sutton. pp. ix, 158. ISBN 0862990882.

- Rivet, A.L.F. & Smith, Colin (1979). The place-names of Roman Britain. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. pp. xviii, 526. ISBN 9780691039534.

- Ross, Catherine (2012). "The Carvetii – a pro-Roman community?". Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society. 3. 12: 55–68. doi:10.5284/1063921.

- Sergent, Bernard (1991). "Ethnozoonymes indo-européens". Dialogues d'histoire ancienne (in French). 17 (2): 9–55. doi:10.3406/dha.1991.1932.