Sausalito, California

Sausalito, California | |

|---|---|

Sausalito combines hillside with shoreline, as seen in this view from Bridgeway, the city's central street. | |

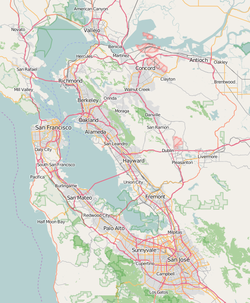

Location in Marin County and the state of California | |

Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 37°51′33″N 122°29′07″W / 37.85917°N 122.48528°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Marin |

| Incorporated | September 4, 1893[1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ian Sobieski[2] |

| • State Senator | Mike McGuire (D)[3] |

| • Assemblymember | Damon Connolly (D)[3] |

| • U. S. Rep. | Jared Huffman (D)[4] |

| • Supervisor | District 3 Kate Sears |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.26 sq mi (5.9 km2) |

| • Land | 1.76 sq mi (4.6 km2) |

| • Water | 0.49 sq mi (1.3 km2) 21.54% |

| Elevation | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 7,269 |

| • Density | 4,120.74/sq mi (1,591.03/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP codes | 94965, 94966 |

| Area codes | 415/628 |

| FIPS code | 06-70364 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 277597, 2411834 |

| Website | www |

Sausalito (Spanish for "small willow grove") is a city in Marin County, California, United States, located 1.5 miles (2.4 kilometers) southeast of Marin City, 8 miles (13 km) south-southeast of San Rafael,[8] and about 4 miles (6 km) north of San Francisco from the Golden Gate Bridge.[6]

Sausalito's population was 7,269 as of the 2020 census.[7] The community is situated near the northern end of the Golden Gate Bridge, and prior to the building of that bridge served as a terminus for rail, car, and ferry traffic.

Sausalito developed rapidly as a shipbuilding center in World War II, with its industrial character giving way in postwar years to a reputation as a wealthy and artistic enclave, a picturesque residential community (incorporating large numbers of houseboats), and a tourist destination. The city is adjacent to, and largely bounded by, the protected spaces of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area as well as the San Francisco Bay.

Etymology

[edit]The name of Sausalito comes from the Spanish sauzalito, meaning "small willow grove", from sauce "willow" + collective derivative -al meaning "place of abundance" + diminutive suffix -ito; with orthographic corruption from z to s due to seseo. Early variants of the name included Saucelito, San Salita, San Saulito, San Salito, Sancolito, Sancilito, Sousolito, Sousalita, Sousilito, Salcido, Sausilito, and Sauz Saulita.[8]

It is sometimes claimed[by whom?] that Sausalito was named for the district in Valparaíso, Chile, where the bandit Joaquín Murrieta was born. Murrieta was the leader of bandits who settled at the northern end of the future Golden Gate Bridge after being banned from San Francisco in the bandit wars. However, this theory is contradicted by sources which state Murrieta was from Mexico, not Chile, and because he did not arrive in California until the Gold Rush around 1849.[9] The Rancho Saucelito had already been granted to William Richardson in 1838.[10]

Geography

[edit]Located at 37°51′33″N 122°29′07″W / 37.85917°N 122.48528°W,[6] Sausalito encompasses both steep, wooded hillside and shoreline tidal flats. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 2.2 square miles (5.7 km2). Notably, only 1.8 square miles (4.7 km2) of it is land. A full 21.54% of the city (0.5 square miles, or 1.3 km2) is underwater, and has been so since its founding in 1868. Prominent geographic features associated with Sausalito include Richardson Bay and Pine Point.

When Sausalito was formally platted, it was anticipated that future development might extend the shoreline with landfill, as had been the practice in neighboring San Francisco. As a result, entire streets, demarcated and given names like Pescadero, Eureka and Teutonia, remain beneath the surface of Richardson Bay.[11] The legal, if not actual, presence of these streets has proved a contentious factor in public policy, because some houseboats float directly above them. According to the San Francisco Chronicle, "State agencies say privately owned houseboats can't be located above the underwater streets because the streets are public trust lands intended for public benefit." The California State Lands Commission is reportedly pursuing a compromise which would move not the houseboats, but the theoretical streets instead.[12]

Climate

[edit]Sausalito has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csb) with far lower temperatures than expected because of its adjacency to San Francisco Bay and the resultant onshore breezes.

| Climate data for Sausalito, California | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 57 (14) |

60 (16) |

62 (17) |

63 (17) |

64 (18) |

67 (19) |

67 (19) |

68 (20) |

70 (21) |

69 (21) |

63 (17) |

57 (14) |

64 (18) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 46 (8) |

48 (9) |

49 (9) |

49 (9) |

51 (11) |

53 (12) |

54 (12) |

55 (13) |

55 (13) |

54 (12) |

50 (10) |

46 (8) |

51 (11) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.50 (114) |

3.61 (92) |

3.26 (83) |

1.46 (37) |

.70 (18) |

.16 (4.1) |

0 (0) |

.06 (1.5) |

.21 (5.3) |

1.12 (28) |

3.16 (80) |

4.56 (116) |

22.80 (579) |

| Source: Weather Channel[13] | |||||||||||||

History

[edit]Indigenous culture

[edit]Sausalito was once the site of a Coast Miwok settlement known as Liwanelowa. The branch of the Coast Miwok living in this area were known as the Huimen (or as Nación de Uimen to the Spanish).[14][15] Early explorers of the area described them as friendly and hospitable. According to Juan de Ayala, "To all these advantages must be added the best of all, which is that the heathen Indians of the port are so faithful in their friendship and so docile in their disposition that I was greatly pleased to receive them on board." European settlers took advantage of the Huimen's kindness and hospitality,[citation needed] and completely massacred[citation needed] them within the span of a few generations. As historian Jack Tracy has observed, "Their dwellings on the site of Sausalito were explored and mapped in 1907, nearly a century and a half later, by an archaeological survey. By that time, nothing was left of the culture of those who had first enjoyed the natural treasures of the bay. The life of the Coastal Miwoks had been reduced to archaeological remnants, as though thousands of years had passed since their existence."

European arrival and settlement

[edit]

The first European known to visit the present-day location of Sausalito was Don José de Cañizares, on August 5, 1775. Cañizares was head of an advance party dispatched by longboat from the ship San Carlos, searching for a suitable anchorage for the larger vessel. The crew of the San Carlos came ashore soon after, reporting friendly natives and teeming populations of deer, elk, bear, sea lions, seals and otters. More significantly for maritime purposes, they reported an abundance of large, mature timber in the hills, a valuable commodity for shipwrights in need of raw materials for masts, braces and planking.

Despite these and later positive reports, the Spanish colonial government of Upper California did little to establish a presence in the area. When a military garrison (now the Presidio of San Francisco) and a Franciscan mission (Mission Dolores) were founded the following year, they were situated on the opposite, southern shore of the bay, where no portage was necessary for overland traffic to and from Monterey, the regional capitol. As a result, the far shore of the Golden Gate strait would remain largely wilderness for another half-century.

The development of the area began at the instigation of William A. Richardson, who arrived in Upper California in 1822, shortly after Mexico had won its independence from Spain. An English mariner who had picked up a fluency in Spanish during his travels, he quickly became an influential presence in the now-Mexican territory. By 1825, Richardson had assumed Mexican citizenship, converted to Catholicism and married the daughter of Don Ignacio Martínez, commandant of the Presidio and holder of a large land grant. His ambitions now expanding to land holdings of his own, Richardson submitted a petition to Governor Echienda for a rancho in the headlands across the water from the Presidio, to be called "Rancho Saucelito".[10] Sausalito is believed to refer to a small cluster of willows, a moist-soil tree, indicating the presence of a freshwater spring.[16]

Even before filing his claim, Richardson had used the spring as a watering station on the shores of what is now called Richardson Bay (an arm of the larger San Francisco Bay), selling fresh water to visiting vessels. However, his ownership of the land was legally tenuous: other claims had been submitted for the same region, and at any rate Mexican law reserved headlands for military uses, not private ownership. Richardson temporarily abandoned his claim and settled instead outside the Presidio, building the first permanent civilian home and laying out the street plan for the pueblo of Yerba Buena (present-day San Francisco). After years of lobbying and legal wrangling, Richardson was given clear title to all 19,751 acres (79.93 km2) of Rancho del Sausalito on February 11, 1838.

Fishing village and sybaritic enclave

[edit]In the post-Gold Rush era, Sausalito's unusual location became a key factor in its formation as a community. It was San Francisco's nearest neighbor, less than two miles (3 km) away at the nearest point and easily seen from city streets, yet transportation factors rendered it effectively isolated. A boat could sail there in under half an hour, but wagons and carriages required an arduous skirting of the entire bay, a journey that could well exceed a hundred miles. As a result, the region was largely dominated by two disparate classes of people, both with ready access to boats: commercial fishermen and wealthy yachting enthusiasts.

Mining town

[edit]In the 1870s, manganese was discovered in the hills west of Old Town that was rich enough to justify small-scale mining. Tunnels were dug near the springs between present-day Prospect Avenue and Sausalito Boulevard. Henry Eames, an opportunistic inventor, built an ore reduction plant at the foot of Main Street to process the manganese ore. This location would become the later site of Sally Stanford’s infamous bordello, Valhalla. However, by 1880 the Saucelito Smelting Works was producing only about fifty tons of black oxide annually, hardly enough to make Sausalito a true mining center.[17]

Transit hub

[edit]The first post office opened in 1870 as "Saucelito" and changed its name to the present spelling in 1887.[8]

In the 1870s, the North Pacific Coast Railroad (NPC) extended its tracks southward to a new terminus in Sausalito, where a rail yard and ferry to San Francisco were established. The NPC was acquired by the North Shore Railroad in 1902, which in turn was absorbed in 1907 by the Southern Pacific affiliate, the Northwestern Pacific.

By 1926, a major auto ferry across the Golden Gate was established from the Sausalito Ferry Terminal, running to the Hyde Street Pier in San Francisco.[18][better source needed] This ferry was an integral part of old U.S. Highway 101, and a large influx of automobile traffic, often parked or idling in long queues, became a dominant characteristic of the town. Northwestern Pacific commuter train service also expanded to serve the increased traffic volume, and Sausalito became known primarily as a transportation hub.

This era came to an end in May 1937 with the opening of the Golden Gate Bridge. The bridge made large-scale ferry operations redundant, and since the new route of Highway 101 bypassed Sausalito entirely, in-town traffic was quickly reduced to a trickle. Car ferry service ended in March 1941 (passenger ferry service, however, continues to this day, linking downtown Sausalito with both the San Francisco Ferry Building in the Embarcadero, and Pier 39 in at Fisherman's Wharf). Northwestern Pacific also closed its Sausalito terminal in March 1941, although some tracks remained in use as "spur tracks" for freight trains as late as 1971.[16]

Bootlegging and rum runners

[edit]Sausalito was a center for bootlegging during the era of Prohibition in the United States. Because of its location facing the Golden Gate and isolated from San Francisco by the same waterway, it was also a favorite landing spot for rum runners.[19] The 1942 film China Girl has some footage of Sally Stanford's Valhalla restaurant on the waterfront. The scene shows the docks and illustrates rum running.

Industrialization during World War II

[edit]When the United States entered World War II, Fort Barry on Point Bonita was reoccupied. Fort Baker also hosted large numbers of troops. Barracks and other housing were constructed for soldiers. Few of these buildings remain.[20]

A major shipyard of the Bechtel Corporation called Marinship was sited along the shoreline of Sausalito. The thousands of laborers who worked here were largely housed in a nearby community constructed for them called Marin City. The soil which supports this area is dredgings from Richardson Bay that were placed during World War II as part of the Marin Liberty Ship shipyards for the United States Navy.[21] A total of 202 acres (0.8 km2) were condemned by the government. A portion of this total area was formed in the shape of a peninsula and this peninsula became known as Schoonmaker Point. In honor of the city's contribution to the war effort, a Tacoma-class frigate was christened the USS Sausalito (PF-4) in 1943. The ship Sausalito, however, was not built in Sausalito but at one of the Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond, California, also on the San Francisco Bay.

The Marinship Shipyards were the site of incidents that provided a key early milestone in the civil rights movement.[22] In 1944 in the case of James v. Marinship the California Supreme Court held that African Americans could not be excluded from jobs based on their race, even if the employer took no discriminatory actions. In the case of Joseph James, on whose behalf the suit was brought, the local Boilermakers Union excluded Blacks from membership and had a "closed shop" contract, forbidding the shipbuilder from employing anyone who was not a member of the union. African American workers could join an auxiliary of the union, which offered access to fewer jobs at lower pay. Future US Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall successfully argued the case, winning a ruling that the union be required to offer equal membership to African Americans. The court extended the ruling to apply explicitly to all unions and all workers in California.

Postwar years

[edit]

Following World War II, the Marinship Shipyards site owner,[23] Donlon Arques,[24][25] a wealthy inland cattle ranch owner, who preferred hanging out in the junkyard, did basically nothing with the property and let nature take its course.[26]

"People drifted in. The curious, the disenfranchised, bohemians... The shipyard was a treasure trove of junk, boats and barges in all possible conditions, a still-functioning marine ways. In the eyes of the square, "normal" Americans, it was a mess. To the creative, i.e., "abnormal" brain, it was a wonderland of seemingly unlimited potential."[26]

A lively waterfront community grew out of the abandoned shipyards. By the late 1960s at least three houseboat communities occupied the waterfront along and adjacent to Sausalito's shore. Beginning in the 1970s, an intense struggle erupted between houseboat residents and developers, dubbed the "Houseboat Wars".[27] Forced removals by county authorities and sabotage by some on the waterfront characterized this struggle. This long fight pitted the waterfront against the "Hill People" – the rich on the hill looking down on the waterfront. Today three houseboat communities still exist — Galilee Harbor in Sausalito, Waldo Point Harbor and the Gates Cooperative, just outside the city limit.

In 1965, the City of Sausalito sued the County of Marin and a developer from Bridgeport, Connecticut named Thomas Frouge[28] for illegally zoning 2,000 acres (809 ha) of land to build a city named Marincello adjacent to Sausalito.[29] The city won the lawsuit in 1970, and the land was transferred as open space to the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. In 1997, The New York Times compared Sausalito to Devonport in Auckland due to its setting and scenery.[30]

In 1972, restaurateur and former San Francisco madam Sally Stanford was elected mayor of the town.

Government

[edit]Federal and state

[edit]In the United States House of Representatives, Sausalito is in California's 2nd congressional district, represented by Democrat Jared Huffman.[31] From 2008 to 2012, Huffman represented Marin County in the California State Assembly.

In the California State Legislature, Sausalito is in:

- the 12th Assembly District, represented by Democrat Damon Connolly[32]

- the 2nd Senate District, represented by Democrat Mike McGuire.

According to the California Secretary of State, as of February 10, 2019, Sausalito has 5,430 registered voters. Of those, 2,905 (53.5%) are registered Democrats, 677 (12.5%) are registered Republicans, and 1,605 (30%) have declined to state a political party.[33]

| Year | Democratic | Republican |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 81.2% 3,824 | 13.5% 636 |

| 2012 | 76.1% 3,535 | 21.6% 1,001 |

| 2008 | 81.2% 4,031 | 17.1% 850 |

| 2004 | 77.0% 3,677 | 21.9% 1,046 |

| 2000 | 67.7% 2,945 | 24.5% 1,067 |

| 1996 | 61.7% 2,579 | 24.7% 1,034 |

| 1992 | 63.2% 3,125 | 19.3% 953 |

| 1988 | 63.4% 2,768 | 35.4% 1,548 |

| 1984 | 56.6% 2,071 | 42.2% 1,542 |

| 1980 | 39.6% 1,369 | 39.5% 1,367 |

| 1976 | 46.5% 1,571 | 49.9% 1,686 |

| 1972 | 58.4% 2,357 | 39.6% 1,600 |

| 1968 | 52.5% 1,638 | 42.4% 1,322 |

| 1964 | 65.7% 1,992 | 34.3% 1,040 |

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 476 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,334 | 180.3% | |

| 1900 | 1,628 | 22.0% | |

| 1910 | 2,383 | 46.4% | |

| 1920 | 2,790 | 17.1% | |

| 1930 | 3,667 | 31.4% | |

| 1940 | 3,540 | −3.5% | |

| 1950 | 4,828 | 36.4% | |

| 1960 | 5,331 | 10.4% | |

| 1970 | 6,158 | 15.5% | |

| 1980 | 7,338 | 19.2% | |

| 1990 | 7,152 | −2.5% | |

| 2000 | 7,330 | 2.5% | |

| 2010 | 7,061 | −3.7% | |

| 2020 | 7,269 | 2.9% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[34] | |||

2010

[edit]The 2010 United States Census[35] reported that Sausalito had a population of 7,061. The population density was 3,128.5 inhabitants per square mile (1,207.9/km2). The racial makeup of Sausalito was 6,400 (90.6%) White, 65 (0.9%) African Americans, 16 (0.2%) Native American, 342 (4.8%) Asian, 10 (0.1%) Pacific Islander, 53 (0.8%) from other races, and 175 (2.5%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 287 persons (4.1%).

The Census reported that 99.8% of the population lived in households and 0.2% lived in non-institutionalized group quarters.

There were 4,112 households, out of which 420 (10.2%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 1,443 (35.1%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 146 (3.6%) had a female householder with no husband present, 64 (1.6%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 313 (7.6%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 63 (1.5%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 1,927 households (46.9%) were made up of individuals, and 524 (12.7%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.71. There were 1,653 families (40.2% of all households); the average family size was 2.39.

The population was spread out, with 615 people (8.7%) under the age of 18, 159 people (2.3%) aged 18 to 24, 1,962 people (27.8%) aged 25 to 44, 2,830 people (40.1%) aged 45 to 64, and 1,495 people (21.2%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 51.1 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.2 males.

There were 4,536 housing units at an average density of 2,009.7 per square mile (775.9/km2), of which 2,088 (50.8%) were owner-occupied, and 2,024 (49.2%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.1%; the rental vacancy rate was 5.8%. 3,783 people (53.6% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 3,265 people (46.2%) lived in rental housing units.

2000

[edit]

As of the census[36] of 2000, there were 7,330 people, 4,254 households, and 1,663 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,852.9 inhabitants per square mile (1,487.6/km2). There were 4,511 housing units at an average density of 2,371.1 per square mile (915.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city in 2010 was 87.4% non-Hispanic White, 0.9% non-Hispanic African American, 0.2% Native American, 4.8% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.3% from other races, and 2.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.1% of the population.

There were 4,254 households, out of which 8.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 33.9% were married couples living together, 3.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 60.9% were non-families. 45.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.72 and the average family size was 2.34.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 7.4% under the age of 18, 2.4% from 18 to 24, 39.5% from 25 to 44, 38.5% from 45 to 64, and 12.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 45 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $87,469, and the median income for a family was $123,467. Males had a median income of $90,680 versus $56,576 for females. The per capita income for the city was $81,040. About 2.0% of families and 5.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 5.1% of those under age 18 and 5.5% of those age 65 or over.

Sister cities

[edit]Sausalito has three sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International:

Sakaide is near the Seto Ohashi Bridge on the north coast of the island of Shikoku in Japan (established in 1988). The primary program is a youth cultural exchange program.

Viña del Mar is located on the coast of Chile not far from Santiago (established 1960). The relationship features a Sausalito Stadium and a Sausalito Lagoon. Conversely, Sausalito's main plaza is named Viña del Mar in honor of the Chilean city. The primary program is 777 (7 women, 7 days, 7 dreams), an entrepreneurial training for Chilean Woman in Sausalito.

Cascais is the newest sister city. This relationship was established in 2013.

Media

[edit]For several decades Sausalito had a local newspaper called the MarinScope,[37] owned at times by Paul and Billy Anderson, and Vijay Mallya. However, as of 2018 the newspaper had ceased publication. Sausalito retains a small radio station founded by Jonathan Westerling, Radio Sausalito 1610 AM, which also serves as the city's Emergency Broadcasting System. The city's primary websites are the city's official site ci.Sausalito.ca.us,[38] the Chamber of Commerce sausalito.org,[39] a reference site oursausalito.com[40] and a guide for locals and visitors to the area Sausalito.com.[41]

Education

[edit]Sausalito is served by the Sausalito Marin City School District for primary school and the Tamalpais Union High School District for secondary school.[42] Effective 2021, the sole public school for the elementary district is Martin Luther King Jr. Academy,[43] with preschool and middle school in Marin City and elementary school in Sausalito.[44]

Previously residents had two public schools to choose from: the K-8 public school, then known as Bayside Martin Luther King Jr. Academy, or the K-8 charter school Willow Creek Academy in Sausalito.[45] Willow Creek occupied ground of the former Bayside School in Sausalito.

There are two private elementary schools: The K-12 Waldorf-style New Village School, and PreK - 5 campus of the Lycée Français de San Francisco. Headlands Preparatory School offers personalized education for middle and high school students. High schoolers in public school attend Tamalpais High School in Mill Valley.[42]

Sausalito City Hall houses the Sausalito Public Library.[46]

Parks and recreation

[edit]

The public parks in Sausalito include Cazneau Playground, Cloud View Park, Dunphy Park, Gabrielson Park, Harrison Playground, Martin Luther King Park and Dog Park, Langendorf Park, Marinship Park, South View Park, Robin Sweeny Park, Tiffany Park, Vina del Mar Plaza, and Yee Tock Chee Park. The public beaches include Schoonmaker Beach, Swede's Beach and Tiffany Beach. Sausalito also has a municipal fishing pier and the Turney Street Boat Ramp. A club house/game room and an exercise room are located in the city hall.[47]

Houseboats

[edit]

The Sausalito houseboat community consists of more than 400 houseboats of various shapes, sizes, and values, along the north end of town, approximately two miles from downtown.[48] While some of these are technically outside the Sausalito city limits, they are generally acknowledged as forming an integral part of the Sausalito community.

The roots of the houseboat community lie in the re-use of abandoned boats and material after the de-commissioning of the Marinship shipyards at the end of World War II. Many anchor-outs came to the area, which created problems with sanitation and other issues. After a series of tense confrontations in the 1970s and 1980s, additional regulations were applied to the area and the great majority of boats were relocated to approved docks. From 77 boats in the water in 1977, there were about 18 boats left in 2019.[citation needed] Several are architect-designed pieces that have been featured in major magazines. The Gates Co-op Houseboat Community remains to this day, although recent action has required them to fit city standards of sanitation and building codes.

The humming toadfish makes mating noises underwater, keeping some residents awake at night.[49][50][51][52][53][54]

Notable people

[edit]The following is a list of notable residents of Sausalito, past and present.

Past

[edit]- Leon Adams, wine writer and author of Wines of America, lived in Sausalito until his death.[55]

- Etel Adnan, Arab-American visual artist, poet, and writer (Also partner Simone Fattal)[56]

- Enid Foster, artist, sculptor, playwright, art community leader[57]

- Phil Frank, cartoonist of "Farley" comic strip in the San Francisco Chronicle. Headed up[clarification needed] placing the Marinship exhibit in the Bay Model and setting up the exhibits in the Ice House Visitor Center.

- Joanie Greggains, fitness influence and media figure, former KGO radio host

- Sterling Hayden, film actor and sailor

- William Randolph Hearst, newspaper publisher[58]

- Janis Joplin, singer (lived in house on 501 Bridgeway)[59]

- Tim Lincecum, San Francisco Giants pitcher[60]

- Baby Face Nelson, gangster of the 1920s[61]

- Frederick O'Brien, writer of travel books about Pacific islands[62]

- Frank Oppenheimer, particle physicist and founder of the Exploratorium in San Francisco

- Harry Partch, composer and creator of musical instruments; set up a studio in an abandoned Sausalito shipyard in 1953[63]

- Otis Redding, musician, wrote "(Sittin' On) The Dock of the Bay" while staying on a houseboat at Waldo Point in Sausalito in 1967.[64]

- Shel Silverstein, poet[58]

- Sally Stanford, former Sausalito City Council member and mayor, founder of the restaurant Valhalla; ran a well-known brothel at 1144 Pine Street in San Francisco[65]

- Alan Watts, 20th-century philosopher[66] (The Sausalito Library owns permanent collections of audio recordings of Watts' spoken words and other material.)[67]

Present-day

[edit]

- Isabelle Allende, author[68]

- Dave Eggers, author and philanthropist

- Neal Gottlieb, ice cream entrepreneur and Survivor: Kaoh Rong contestant[69]

- Isabella Kirkland, visual artist and biodiversity researcher[70][71]

- Vijay Mallya, Indian liquor magnate[72]

- Jason Roberts, author and technologist[73]

- Amy Tan, author[74]

- Chase Utley, Major League Baseball player

Industry

[edit]

- Heath Ceramics, founded by mid-century modern ceramicist Edith Heath, has been operating in Sausalito since 1948.

- From 1972 to 2008, the Record Plant recording studio operated from a 10,000 square foot complex on the Sausalito waterfront. The hundreds of albums recorded there include Fleetwood Mac's Rumours, Stevie Wonder's Songs in the Key of Life, and Heart's eponymous debut.

- In addition to Marinship, which built ships during World War II, Sausalito has a long history of boatbuilding. These boatyards specialized in a variety of vessels, including fishing and other work boats, government-contract vessels and recreational yachts. Many boatyards came and went in Sausalito in the late 19th century and early 20th century, including G. Smith, Brixen and Manfrey, the California Launch Building Company, the Reliance Boat Company, Nunes Brothers (Manuel and Antonio), Atlantic Boatbuilding Plant, Crichton and Arques, Sausalito Shipbuilding, Madden and Lewis Company, Menotti Pasquinucci and Bob's Boatyard. After World War II, the best known yards are, or were, Spaulding Boatworks, Bob's Boatyard, Easom Boatworks, Sausalito Marine, Bayside Boatworks, Richardson Bay Boat, the Boatbuilders Co-op and Anderson's Boat Yard.[75]

- The Spaulding Boatworks was founded in 1951 by Myron Spaulding and has been in continuous operation since then. It is one of the last remaining wooden boat yards on the West Coast. Today, the Spaulding Wooden Boat Center is a working and living museum, with a mission to restore and return to active use significant, historic wooden sailing vessels; preserve and enhance its working boatyard; create a place where people can gather to use, enjoy, and learn about wooden boats; and educate others about wooden boat building skills, traditions and values.

- Mason's Distillery,[76] acquired by the American Distilling Company in 1933, manufactured and distributed various brands of whiskey, including "Bourbon Supreme". The distillery was destroyed by fire on May 4, 1963; the site is now the location of "Whiskey Springs" condominiums.

- The Southern Pacific ferryboat Berkeley was docked in Sausalito for several years during the 1960s after being taken out of service. It was subsequently towed to San Diego where it was restored and is a tourist attraction.

- The bakery Pepperidge Farm, which markets The American Collection line of cookies named after various notable locales (Chesapeake, Nantucket, Tahoe), has given the name Sausalito to their milk chocolate/macadamia-nut combo. It is not manufactured in the city. As of 2011, the company maintains a registered trademark on the name Sausalito.[77]

In popular culture

[edit]Books, film, television, and video games

[edit]- A section of the 1892 novel The Wrecker, by Robert Louis Stevenson and Lloyd Osborn, is set in Sausalito.

- The opening of The Sea-Wolf by Jack London is set on a ferryboat travelling from Sausalito to San Francisco. It is believed that London stayed for a time in Sausalito while he was writing the novel.

- Scenes in the 1947 film The Lady from Shanghai, directed by Orson Welles, take place on the Sausalito waterfront with Rita Hayworth.

- The 1949 film Impact, directed by Arthur Lubin, features downtown Sausalito in its opening scenes.

- In Jack Kerouac's 1957 novel On the Road, Sausalito is mentioned as "a little fishing village" and a joke is made about it being "filled with Italians".

- Many scenes in the 1965 film Dear Brigitte with James Stewart, Glynis Johns, Ed Wynn, Bill Mumy, and Fabian Forte were filmed on the Sausalito shores of Richardson Bay.

- The 1968 film Petulia has Richard Chamberlain fishing Julie Christie out of the water at the foot of Johnson Street. Potted trees and other shrubbery, situated as set decorations on the adjacent docks, were left in place after filming had ended.

- M*A*S*H fictional character B. J. Hunnicutt was portrayed as having completed his medical residency in Sausalito (an impossibility, as the town has never had a hospital). His peacetime address is in Mill Valley, the town adjacent to Sausalito. He also mentions several times going to "a nice restaurant in Sausalito with his wife, Peg".

- A scene from the 1972 movie Play It Again, Sam was shot using interiors of the Trident restaurant and exteriors of the Spinnaker restaurant in Sausalito. In the film, actors Woody Allen and Tony Roberts are seen entering the Spinnaker restaurant with the ferryboat Berkeley, then tied up in Sausalito with the retail emporium Trade Fair in the background. The scene then cuts to the interior of the Trident.

- In The Second Coming of Suzanne (1974), Paul Sand and Sondra Locke's characters reside on a houseboat in Sausalito. The historic No Name Bar was among the locations used for the movie.

- In the 1978 comic farce mystery detective thriller Foul Play, Gloria Mundy (played by Goldie Hawn) comes under the protection of San Francisco detective Lt. Tony Carlson (played by Chevy Chase), who brings her to his houseboat in Sausalito.

- The Sally Stanford biopic Lady of the House (1978), starring Dyan Cannon, was filmed primarily in Sausalito.

- The 1978 film Invasion of the Body Snatchers by Philip Kaufman has a scene in front of the Health Department of San Francisco where alien pods are distributed. A speaker says: "You are in the right place for Sausalito. Please keep moving right along. Sausalito only, please."

- The 1978 film The Manitou by William Girdler mentions doctor of anthropology, Dr. Snow played by Burgess Meredith as living in Sausalito, where main characters meet him.

- In the 1978 novel The House of God, the intern Hooper hails from Sausalito.

- Parts of the 1980 satire Serial were filmed in the Sausalito ferry parking lot.

- In Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home, the fictional Cetacean Institute is in Sausalito. Although several scenes took place there, no filming was done in Sausalito itself. The actual filming location for the fictional institute was the Monterey Bay Aquarium in Monterey, California.

- Craig Thomas set the home of Alan Aubrey in Sausalito in his 1990 thriller The Last Raven.

- Albert Brooks' Mother (1996) employs the town as the setting for its story, which features several shots of Sausalito throughout.

- In David Fincher's 1997 film The Game, set in San Francisco, Nicholas Van Orton's (Michael Douglas) ex-wife lives in Sausalito.

- Sausalito is the English title of a 2000 Hong Kong film directed by Lau Wai Keung, starring Maggie Cheung.

- In the television series Star Trek: Enterprise, a Vulcan "compound" is based in Sausalito, although it is not depicted; Fort Baker, which borders Sausalito is shown, and has become the site of Starfleet Headquarters. In Rise of the Federation - Uncertain Logic, set in 2165, Admiral Jonathan Archer lives in a houseboat in Sausalito.

- In Sofia Coppola's 2003 film Lost in Translation, a jazz band called Sausalito performs at the Park Hyatt Bar.

- In the 2005 video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, there is a town based on Sausalito, named Bayside.

- Judd Apatow's 2009 dramedy Funny People uses Sausalito as the backdrop for the film's third act where Leslie Mann and Eric Bana's characters live with their family.

- 2010 racing video game Blur featured a track ostensibly set in Sausalito, although the game track does not resemble the actual landscape.

- The 2012 ABC series Red Widow was based in Sausalito. However, it was actually filmed in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. The series' main stars were Radha Mitchell and Goran Visnjic.

- The 2014-2016 TNT series, Murder in the First, the main detective character lives on a Sausalito houseboat.

- Sausalito is one of the cities featured in the 2016 video game Watch Dogs 2, alongside San Francisco and Oakland.

- In the 2021 film The Addams Family 2, the family visits Sausalito.

Music

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2007) |

- "(Sittin' On) The Dock of the Bay" by Otis Redding was written by the R&B singer in 1967 as he sat on a rented houseboat docked at Commodore Seaplane Base in Sausalito.[78] Though it may be the most famous musical reference to Sausalito's geography, it remains an oblique one as the city is not specifically named.

- "Sausilito", a top ten hit for Netherlands duo Rosy & Andres in 1975

- "Sausalito", Dead Fish (band), Vitória, 2015

- "Head Like a Rock", Ian McNabb, 1994

- "Postcard", Roddy Frame, Seven Dials, 2014

- "Jack Kerouac", Brooke Fraser, Flags, 2010

- "Sausalito", George Duke, Duke, 2005

- "Sausalito (The Governor's Song)", Bobby Darin, 1969

- "Sausalito Summernight", Diesel, 1980-1981 (#25 - Billboard,[79] #1 in Canada[80])

- "Samba de Sausalito", Santana, Welcome, 1973 album

- "Mr. Don", The Disco Biscuits

- "Sausalito", Grover Washington, Jr., Grover Washington Live in Concert, 1977

- "Sausalito (is the Place to Go)", Ohio Express "Best of Ohio Express"

- "Sausalito", Conor Oberst, "Conor Oberst" 2008

- "One Way Ticket" by Mimi and Richard Fariña in Celebrations for a Grey Day

- "Sausalito", Los Abatidos, Los Abatidos, 1999.

- "Let It Flow (Sausalito Calling)", Camelle Hinds, "Soul Degrees", 1996

- "Sausalito in the Summertime" Benita Hill[81]

- "Real Emotional Trash", Stephen Malkmus and the Jicks, Real Emotional Trash, 2008.

- "Don't Let Up", Night Ranger, Don't Let Up, 2017

- ”Sausalito”, Larry June, Very Peaceful, 2017

- ”6am in Sausalito”, Larry June, Orange Print, 2021

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "City Council". Sausalito, CA. Retrieved March 27, 2024.

- ^ a b "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ "California's 2nd Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ "2021 U.S. Gazetteer Files: California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Sausalito". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ a b "P1. Race – Sausalito city, California: 2020 DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c Durham, David L. (1998). California's Geographic Names: A Gazetteer of Historic and Modern Names of the State. Clovis, Calif.: Word Dancer Press. p. 699. ISBN 1-884995-14-4.

- ^ *"Review: Roaring Camp: The Social World of the California Gold Rush", American Scholar, January 1, 2000, p. 142 Vol. 69 No. 1 ISSN 0003-0937

- ^ a b Robert Ryal Miller, Captain Richardson, Mariner, Ranchero, and Founder of San Francisco Berkeley: La Loma Press, 1995 [Call number at SSU: Regional Room F869 .S353 R546] 1995

- ^ Greg Lucas, Chronicle Sacramento Bureau (June 15, 2006). ""Now, houseboats not really sunk: Assembly bill seeks to legalize mooring on public property", San Francisco Chronicle, June 15, 2006". Sfgate.com. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ Greg Lucas, Chronicle Sacramento Bureau (June 15, 2006). "op. cit., San Francisco Chronicle, June 15, 2006". Sfgate.com. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ Average weather for Sausalito Weather Channel Retrieved December 22, 2012

- ^ Peterson, Bonnie J. (1976). Dawn of the World: Coast Miwok Myths. ISBN 0-912908-04-1

- ^ National Park Service. (2005). Cultural Landscape Report for Fort Baker, Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

- ^ a b Tracy, Jack. Sausalito Moments in Time: A Pictorial History of Sausalito 1850-1950. Sausalito:Windgate Press 1983. ISBN 0-915269-00-7

- ^ Tracy, Jack."Sausalito Moments in Time."Sausalito, California: Windgate Press, 1983.

- ^ http://webbie1.sfpl.org/multimedia/sfphotos/AAC-2256.jpg [bare URL image file]

- ^ SF Chronicle, December 5, 2008, pp. A1, A20.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Historic California Posts: Fort Barry". Militarymuseum.org. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ Soils testing results for the Liberty Ship building site, Sausalito California, EMI report 7291W2, City of Sausalito Community Development Department, November 1989

- ^ ""The decision was an important victory in the fight to end segregation in the work place and the fight for civil rights for all workers regardless of color.", BlackPast.org, accessed April 29, 2010". Blackpast.org. January 24, 2007. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ "Godfather of the Waterfront". The Sausalito Historical Society. December 1, 2021. Retrieved August 11, 2024.

- ^ "Conversations with Donlon Arques". The Sausalito Historical Society. March 8, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2024.

- ^ "THE DONLON ARQUES HISTORICAL RESEARCH PROJECT". Arques School of Traditional Boatbuilding. Retrieved August 11, 2024.

- ^ a b Costello, Jeff (August 21, 2013). "Sausalito Houseboat War, 1971". Anderson Valley Advertiser. Retrieved August 11, 2024.

- ^ Larry Clinton (August 2001). "A Short History of Liveaboards on the Bay". Bay Crossings. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018.

- ^ "Casa Frouge, Bridgeport's First Luxury Apartment Building". Bridgeport History Center. Retrieved August 11, 2024.

- ^ Olsen, Lauren. "From dream development to sunset scope: The story of Marincello's abandoned dream". Redwood Bark. Retrieved August 11, 2024.

- ^ In Auckland, Life Is Alfresco – The New York Times, October 5, 1997

- ^ "California's 2nd Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ "Members Assembly".

- ^ "CA Secretary of State – Report of Registration – February 10, 2019" (PDF). ca.gov. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Sausalito city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Marinscope Newspapers > Front". Marinscope.com. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ "City of Sausalito : Home". Ci.sausalito.ca.us. May 18, 2012. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ "Visit Sausalito, CA | Sausalito Chamber of Commerce". Sausalito.org. May 11, 2012. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ "Our Sausalito.com". Our Sausalito.com. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ "Sausalito California Hotels, Restaurants, Real Estate, Shopping". Sausalito.com. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ a b "SCHOOLS in the Tamalpais Union High School District and communities served Archived August 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine." Tamalpais Union High School District. Retrieved on April 1, 2010.

- ^ Brenner, Keri (June 7, 2021). "Sausalito Marin City School District gears for desegregation". Marin Independent Journal. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ Brenner, Keri (March 20, 2021). "Sausalito Marin City School District sets unification date". Marin Independent Journal. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "K-8 Comprehensive Education Program." School(Archive) Sausalito Marin City School District. Retrieved on February 3, 2013.

- ^ "Hours and Directions." Sausalito Public Library. Retrieved on January 26, 2017. ""

- ^ "Parks & Facilities." City of Sausalito. Retrieved on February 4, 2013.

- ^ Kristine M. Carber (October 4, 2003). "Floating Through Life, Sausalito houseboat community will show off its one-of-a-kind dwellings on Sunday". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ Hum along with male plainfin midshipman fish. Morning Edition. National Public Radio. July 29, 2009.

- ^ Bishop, K. Sausalito Journal; Voice of the turtle? No, toadfish love song. The New York Times. June 26, 1989.

- ^ Sounds of the Plainfin Midshipman. Underwater Sound from the RTC Pier. Underwater Acoustics Research Group. San Francisco State University.

- ^ Perlman, D. Hormones fine-tune the humming toadfish: High levels of estrogen found in the most responsive females. San Francisco Chronicle. July 19, 2004.

- ^ Toadfish's steamy love life is revealed / Singing fish sometimes let meek males join a ménage à trois San Francisco Chronicle

- ^ The humming toadfish story

- ^ Goldberg, Howard G. (September 16, 1995). "Leon Adams, Wine Expert And Writer, 90". Obituaries. The New York Times. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- ^ "The Luminous Abstractions of Etel Adnan". The New Yorker. October 1, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ Hayes, Allan and Carol (2019). Enid Foster, 1895-1979: Artist, Sculptor, Poet, Playwright, Creative Force, Ringleader, Cultural Icon. Petaluma, CA: Roundtree Press. ISBN 9781949480023.

- ^ a b "Sausalito - Beat Bossart". www.beatbossart.com. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ Bulwa, Demian (April 20, 2009). "Sausalito woman found dead, boyfriend arrested". SFGATE. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- ^ Lee, Henry K.; Wildermuth, John (October 7, 2011). "Lincecum trashed S.F. townhouse, suit claims". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ San Francisco Chronicle, Dec.5, 2008, p. A20.[full citation needed]

- ^ Geiger, Jeffrey (2007), Facing the Pacific, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp 74-117

- ^ Partch, Harry (2000). McGeary, Thomas (ed.). Bitter Music: Collected Journals, Essays, Introductions, and Librettos. University of Illinois Press. p. xxi. ISBN 978-0-252-06913-0.

- ^ San Francisco Chronicle, February 4, 2009, p. E3.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Profile of life history of Sally Stanford". Mistersf.com. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ^ Charters, Ann (ed.). The Portable Beat Reader. Penguin Books. New York. 1992. ISBN 0-670-83885-3

- ^ "Alan Watts Collections". sausalitolibrary.org/. July 26, 2022. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ "Isabel Allende". Fanmail.biz. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- ^ Neal Gottlieb - Survivor Cast Member, retrieved July 27, 2020

- ^ Surtees, Joshua. "If you're going to San Francisco – stay on a stylish Sausalito houseboat," The Guardian, June 28, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Larson, Vicki. "Isabella Kirkland paints disappearing species—and newfound ones—with scientific detail," Marin Independent Journal, October 15, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Fost, Dan (June 24, 2011). "Vijay Mallya is not your typical brewer / Owner of Mendocino Brewing Co. is a member of India's Parliament - and more". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "Brief Bio". Jason Roberts. Archived from the original on February 6, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- ^ "Amy Tan on Joy and Luck at Home". Wall Street Journal. July 30, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- ^ Sausalito Historical Society. Sausalito (Images of America). San Francisco: Arcadia Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-7385-3036-0

- ^ "Mason Distillery". Search Term Record. Sausalito Historical Society.

- ^ "Sausalito® Milk Chocolate Macadamia". Our products. Pepperidge Farm. Archived from the original on June 1, 2012.

- ^ Bowman, Rob (2007). Liner Notes for Dreams to Remember: The Otis Redding Story [DVD]. Beverly Hills, CA: Reelin' in the Years Productions/Concord Music Group.

- ^ "Diesel - Billboard Hot 100 History". Billboard.com. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ "RPM Weekly - Week of September 5, 1981 - RPM Top 50 Singles". bac-lac.gc.ca. July 17, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ "Sausalito in the Summertime: Benita Hill: MP3 Downloads". Amazon. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Tracy, Jack. Sausalito Moments in Time: A Pictorial History of Sausalito 1850–1950. Sausalito:Windgate Press 1983. ISBN 0-915269-00-7.

- Sausalito Historical Society. Sausalito (Images of America). San Francisco: Arcadia Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0-7385-3036-0.