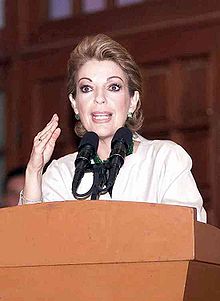

Marta Sahagún

Marta Sahagún | |

|---|---|

| |

| First Lady of Mexico | |

| In role 2 July 2001 – 30 November 2006 | |

| President | Vicente Fox |

| Preceded by | Nilda Patricia Velasco |

| Succeeded by | Margarita Zavala |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Marta María Sahagún Jiménez April 10, 1953 Zamora, Michoacán, Mexico |

| Political party | National Action Party |

| Spouses | |

| Children | Fernando Bribiesca Sahagún Jorge Alberto Godoy Manuel Godoy |

Marta Sahagún (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈmaɾta sa(a)ˈɣun]; born Marta María Sahagún Jiménez (10 April 1953) served as the First Lady of Mexico from 2 July 2001, when she married President Vicente Fox, until he left office on 30 November 2006. Her tenure was marked by her outspoken views and active role in her husband's administration, in contrast to previous First Ladies of Mexico, as well as several controversies regarding her nonprofit Vamos México foundation and her family's business dealings.[1][2]

Early life and teaching

[edit]Sahagún was born in Zamora, Michoacán, the second of six children, to Dr. Alberto Sahagún de la Parra, who founded Zamora’s San José Hospital and a nursing school, and Ana Teresa Jiménez Vargas. For some years she worked as an English teacher at the Universidad Lasallista Benavente. Her first marriage was to veterinarian Manuel Bribiesca Godoy, with whom she ran a veterinary wholesale supplies business in Celaya, Guanajuato.[3] They had three children: Manuel, Jorge Alberto and Fernando. They separated in 1998 and divorced in 2000.

Political career

[edit]Sahagún has been an active member of the National Action Party since 1988. She unsuccessfully ran for mayor of Celaya and met Vicente Fox, who named her as his spokeswoman for his government in Guanajuato. Sahagún continued to serve as his press secretary during his successful presidential campaign and for his first year in office. Sahagún married Fox in 2001.[4]

In September 2001, Sahagún created the Vamos México (Let’s Go Mexico) foundation, which allocates funds to help marginalized people of the country and other organizations such as the Legion of Christ. Vamos México was inaugurated with a concert by Elton John in Chapultepec Castle, which drew criticism for using a national monument for a private function.[5] The foundation came under national and international scrutiny after an investigation by The Financial Times found that less than half of the foundation's donations went toward charitable efforts. The Financial Times criticized the foundation's lack of transparency in the management of its resources, the source of its donations and its high overhead costs, despite its access to presidential staff, resources and donated office space.[6] The federal auditor also opened an investigation into whether the national lottery and the president's office had improperly channeled public funds into the foundation. The lottery's then-director, Laura Valdés, is the sister of a board member of Vamos México.[7]

In response, Vamos México bought full-page ads in Mexican newspapers with a pie chart breakdown of its expenses, which added up to 103.26 percent.[8]

Despite her popularity with the public, Sahagún was criticized by legislators and media for using her position as First Lady to set up a future run for the presidency.[9][10] She was also criticized for her spending habits, including her publicly funded staff of 38, with the top 11 employees costing a total of $782,000 a year.[11]

Despite admitting her interest in the presidency,[12] Sahagún confirmed in 2004 that she would not become a candidate for president and would retire to her and her husband's ranch, although she added, "Mexico is ready to be governed by a woman."[13]

Controversies

[edit]Conflict with Proceso and Olga Wornat

[edit]In 2003, Argentine journalist Olga Wornat published La Jefa: Vida pública y privada de Marta Sahagún de Fox ("The Chief: The Public and Private Life of Marta Sahagun de Fox"), a book about Marta Sahagún and her sons. Federal deputy Ricardo Sheffield Padilla asked the federal government to investigate the claims of corruption raised by Wornat. In 2005, Wornat published a second book about Sahagún and her sons, Crónicas Malditas ("Accursed Chronicles"), which investigated the sources of their immense fortune. The Mexican magazine Proceso also published an article the same year about the dissolution of Sahagún's first marriage (including claims of domestic violence against her then-husband) and about the "suspicious" businesses of Sahagún's sons.

On May 3, 2005, Marta Sahagún filed a civil lawsuit before the Tribunal Superior de Justicia del Distrito Federal (Supreme Tribunal of Justice of the Federal District) against Wornat and Proceso for "moral damages" and breach of privacy. Sahagún’s son Manuel Bibriesca Sahagún filed a separate lawsuit against Wornat, who had received death threats since her books were published and had been placed under house arrest by a federal judge.[14]

On November 27, 2005, Proceso published an article titled "Amistades Peligrosas" ("Dangerous Friendships"), wherein Raquenel Villanueva, a prominent lawyer for drug kingpins, said she had met Fernando Bribiesca Sahagún with her client Jaime Valdez Martínez in 2003.[15] The Procuraduría General de la República considers Valdez a representative of drug cartel leader Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán.[citation needed]

The Bribiesca sons

[edit]Sahagún and her sons have been repeatedly accused of using her influence to promote their business interests.[16] Partly as a result of the revelations of journalist Olga Wornat, the Mexican Chamber of Deputies launched investigations into the activities of Sahagun’s sons. In mid-2006, a commission of the Chamber of Deputies, chaired by Deputy Jesús González Schmal, allegedly found evidence that would prove multiple shady dealings in the affairs of Sahagun’s children and decided to raise a complaint with the Attorney General's Office. Upon hearing the report, Sahagún held a press conference at the official residence of Los Pinos to harshly criticize the commission and González Schmal, claiming that it was lies and a publicity stunt against her.[17]

Mexican journalist Anabel Hernández, in her books Fin de fiesta en Los Pinos (2006) and Narcoland (2012) contributed to increasing criticism of Sahagún and her sons by investigating the Bribiescas’ alleged influence peddling and their links to drug cartels.

Manuel and Jorge Bribiesca Sahagún reportedly played a key role in facilitating multimillion-dollar contracts with state-owned Pemex on behalf of Oceanografia, an oil services company that was later accused of defrauding Citigroup and Banamex of at least $400 million.[18]

In 2012, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation issued an arrest warrant for Manuel Bribiesca on charges of fraud in relation to the Oceanografia case.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Castillo, E. Eduardo (19 June 2006). "Mexican Candidates' Wives Seek Low Profile". The Associated Press. The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Scott C. (19 July 2004). "Worst Lady? President Vicente Fox Is Losing His Grip on His Party and His Government, and His Wife May Be to Blame". Newsweek. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Kraul, Chris (5 July 2001). "Fox's First Lady Sizing Up Her New Shoes". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ Kraul, Chris (5 July 2001). "Fox's First Lady Sizing Up Her New Shoes". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ Tuckman, Jo (9 November 2001). "Images of Evita and Elton trouble Mexican first lady". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Silver, Sara (15 June 2004). "First lady's foundation that finds itself on shaky ground". The Financial Times. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ Silver, Sara; Authers, John (1 July 2004). "Mexico to probe lottery donations". The Financial Times. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ "Numbers game". The Financial Times. 29 June 2004. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ Sullivan, Kevin (8 July 2004). "Mexico's First Lady: Asset or Liability?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Kraul, Chris (5 July 2001). "Fox's First Lady Sizing Up Her New Shoes". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ Silver, Sara (13 May 2005). "Mexico to limit First Lady's public spending". The Financial Times. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Cevallos, Diego (13 February 2004). "First Lady's Political Ambitions Draw Fire". Inter Press Service News Agency. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Reed (13 July 2004). "Mexican First Lady Rules Out a Presidential Bid". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "Son of president's wife sues journalist". en.rsf.org. Reporters Without Borders. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ "Amistades Peligrosas". Proceso. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Tuckman, Jo (2012). Mexico: Democracy Interrupted. Yale University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-300-16031-4. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Alcántara, Liliana (29 July 2006). "Marta Sahagún descalifica acusación por caso Bribiesca". El Universal. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ Estevez, Dolia (24 March 2014). "Oceanografía's Mexican CEO Turns Himself In For Questioning On Alleged Massive Fraud Against Citigroup". Forbes. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ "FBI looking for the stepson of Mexico's Ex-President". San Diego Red. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

External links

[edit]- Mexico's first lady eyes following Fox to presidency

- El Balero: Marta Sahagún de Fox

- (in Spanish) Univisión: Primera dama mexicana quiere presidencia

- Presidencia de la República: Marta de Fox (official bio)

- (in Spanish) Vamos Mexico response to the Financial Times

- Sahagún sues journalist and Mexican magazine

- Reporters Without Borders articles about the Sahagún family relations with Olga Wornat