Thomas Davenport (inventor)

Thomas Davenport | |

|---|---|

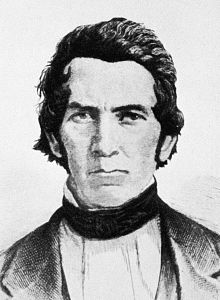

Davenport c. 1850 | |

| Born | July 9, 1802 Williamstown, Vermont, United States |

| Died | July 6, 1851 (aged 48) |

| Resting place | Pine Hill Cemetery, Brandon, Vermont |

| Occupation(s) | Blacksmith Inventor |

| Employer | Orange Smalley |

| Known for | inventing the electric motor |

| Spouse | Emily (Goss) Davenport (m. 1827-1851, his death) |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

Thomas Davenport (July 9, 1802 – July 6, 1851) was a Vermont blacksmith who, with his wife Emily, constructed the first American DC electric motor in 1834.[1]

Biography

[edit]Davenport was born in Williamstown, Vermont. He lived in Forest Dale, a village in the town of Brandon.

As early as 1834, he developed a battery-powered electric motor, along with his wife Emily Davenport. They used it to operate a small model car on a short section of track, paving the way for the later electrification of streetcars.[2] It is the first attempt to apply electrification to locomotion.[3]

Davenport's 1833 visit to the Penfield and Taft iron works at Crown Point, New York, where an electromagnet was operating, based on the design of Joseph Henry, was an impetus for his electromagnetic undertakings. Davenport bought an electromagnet from the Crown Point factory and took it apart to see how it worked. Then he forged a better iron core and redid the wiring, using silk from his wife's wedding gown.[4]

With his wife Emily and colleague Orange Smalley, Davenport received the first American patent on an electric machine in 1837, U. S. Patent No. 132.[5] In 1840, he printed The Electro-Magnetic and Mechanics Intelligencer, making it the first magazine to be printed with electricity.[6]

In 1849, Charles Grafton Page, the Washington scientist and inventor, commenced a project to build an electromagnetically powered locomotive, with substantial funds appropriated by the US Senate. Davenport challenged the expenditure of public funds, arguing for the motors he had already invented. In 1851, Page's full sized electromagnetically operated locomotive was put to a calamity-laden test on the rail line between Washington and Baltimore.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Thomas Davenport Archived October 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Electrifying America by David E. Nye, p. 86, from Google Books. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ Leuzzi, Vincenzo (1947). Tecnica ed economia dei trasporti (in Italian). Rome: Edizioni moderne. p. 3.

- ^ Schiffer, 2008, pp. 65-66.

- ^ "Improvement in propelling machinery by magnetism and electro-magnetism". Retrieved February 27, 2011.

- ^ The Electrical Journal. D. B. Adams. September 9, 1882. p. 399. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ^ Post,(1976), pp. 89-90.

Further reading

[edit]- Post, R. C. (1976). Physics, Patents, and Politics: A Biography of Charles Grafton Page. New York: Science History Publications.

- Michael Brian Schiffer, 2008. Power Struggles: Scientific Authority and the Creation of Practical Electricity Before Edison, Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

- Frank Wicks. "The Blacksmith's Motor. Electricity, magnetism, and motion: A self-taught Vermonter pointed the direction for lighting the world." Mechanical Engineering, July 1999.

- Davenport's patent for the electric motor, issued in early 1837, Today in Technology History February 25 (direct link)

- Smalley and Davenport's shop

- The invention of the electric motor 1800–1854: Thomas Davenport