Rest (music)

A rest is the absence of a sound for a defined period of time in music, or one of the musical notation signs used to indicate that.

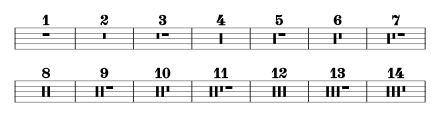

The length of a rest corresponds with that of a particular note value, thus indicating how long the silence should last. Each type of rest is named for the note value it corresponds with (e.g. quarter note and quarter rest, or quaver and quaver rest), and each of them has a distinctive sign.

Description

[edit]Rests are intervals of silence in pieces of music, marked by symbols indicating the length of the silence. Each rest symbol and name corresponds with a particular note value, indicating how long the silence should last, generally as a multiplier of a measure or whole note.

| American English | British English | Multiplier | Symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longa | Long rest | 4 | |

| Double whole rest | Breve rest | 2 | |

| Whole rest | Semibreve rest | 1 | |

| Half rest | Minim rest | 1⁄2 | |

| Quarter rest | Crotchet rest | 1⁄4 | |

| Eighth rest | Quaver rest | 1⁄8 | |

| Sixteenth rest | Semiquaver rest | 1⁄16 | |

| Thirty-second rest | Demisemiquaver rest | 1⁄32 | |

| Sixty-fourth rest | Hemidemisemiquaver rest | 1⁄64 |

- The quarter (crotchet) rest

(𝄽) may take a different form

(𝄽) may take a different form  in older music.[1][2][3]

in older music.[1][2][3] - The four-measure rest or longa rest are only used in long silent passages which are not divided into bars.[citation needed]

- The combination of rests used to mark a silence follows the same rules as for note values.[4]

One-bar rests

[edit]When an entire bar is devoid of notes, a whole (semibreve) rest is used, regardless of the actual time signature.[4] Historically exceptions were made for a 4

2 time signature (four half notes per bar), when a double whole (breve) rest was typically used for a bar's rest, and for time signatures shorter than 3

16, when a rest of the actual measure length would be used.[5] Some published (usually earlier) music places the numeral "1" above the rest to confirm the extent of the rest.

Occasionally in manuscripts and facsimiles of them, bars of rest are sometimes left completely empty and unmarked, possibly even without the staves.[6]

Multiple measure rests

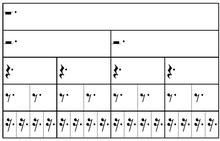

[edit] |

|

In instrumental parts, rests of more than one bar in the same meter and key may be indicated with a multimeasure rest (British English: multiple bar rest), showing the number of bars of rest, as shown. A multimeasure rest is usually drawn in one of two ways:

- As a thick horizontal line placed on the middle line of the staff, with serifs at both ends (see above middle picture),[1] or as thick diagonal lines placed between the second and fourth lines of the staff, resembling a large heavy minus sign or equals sign set at a slant (the diagonal style is much less common than the horizontal one; although a small number of publishers use it, it is more commonly found in modern manuscripts in a casual style).[5] Both variants of thick line rests are drawn in the same shape each time, regardless of how many bars' rest they represent.

- The older system of notating multirests (deriving from Baroque notation conventions that were adapted from the old mensural rest system dating from Medieval times) draws each multimeasure rest according to the picture above right unless it will exceed a certain number of bars; rests longer than that limit are drawn using the thick horizontal line mentioned above. How long a multimeasure rest must be before resorting to a horizontal line is a matter of personal taste or editorial policy; most publishers use ten bars as the changing point, however, larger and smaller changing points are used, especially in earlier music.[1]

The number of bars for which a horizontal line multimeasure rest lasts is indicated by a number printed above the musical staff (usually at the same size as the numerals in a time signature). If a change of meter or key occurs during a multimeasure rest, that rest must be divided into shorter sections for clarity, with the changes of key and/or meter indicated between the rests. Multimeasure rests must also be divided at double barlines, which demarcate musical phrases or sections, and at rehearsal letters.

Dotted rests

[edit]

A rest may also have a dot after it, increasing its duration by half, but this is less commonly used than with notes, except occasionally in modern music notated in compound meters such as 6

8 or 12

8. In these meters the long-standing convention has been to indicate one beat of rest as a quarter rest followed by an eighth rest (equivalent to three eighths). See: Anacrusis.

General pause

[edit]In a score for an ensemble piece, "G.P." (general pause) indicates silence for one bar or more for the entire ensemble.[7] Specifically marking general pauses each time they occur (rather than writing them as ordinary rests) is relevant for performers, as making any kind of noise should be avoided there—for instance, page turns in sheet music are not made during general pauses, as the sound of turning the page becomes noticeable when no one is playing.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c History of Music Notation (1937) by C. Gorden, p. 93.[full citation needed]

- ^ Examples of the older form are found in the work of English music publishers up to the 20th century, e.g., W. A. Mozart Requiem Mass, vocal score ed. W. T. Best, pub. London: Novello & Co. Ltd. 1879.

- ^ Rudiments and Theory of Music Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music, London 1958. I, 33 and III, 25. The former shows both forms without distinction, the latter the "old" form only. The book was the standard theory manual in the UK up until at least 1975. The "old" form was taught as a manuscript variant of the printed form.

- ^ a b AB guide to music theory by E. Taylor, chapter 13/1, ISBN 978-1-85472-446-5

- ^ a b Music Notation: A Manual of Modern Practice, second edition, by Gardner Read (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1969): 98. (Reprinted, New York: Taplinger Publishing Company, 1979).

- ^ "Aesthetic Functions of Silence and Rests in Music", by Zofia Lissa, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 22 (1964), no. 4: 443–54 doi:10.2307/427936.

- ^ Elaine Gould, Behind Bars – The Definitive Guide to Music Notation, p. 190. Faber Music (publisher), 2011.

- ^ Elaine Gould, Behind Bars – The Definitive Guide to Music Notation, p. 561. Faber Music (publisher), 2011.