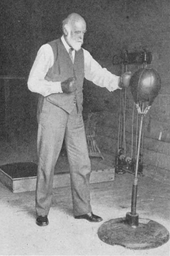

Oliver Lodge

Oliver Lodge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Oliver Joseph Lodge 12 June 1851 Penkhull, Stoke-on-Trent, England |

| Died | 22 August 1940 (aged 89) Wilsford cum Lake, Wiltshire, England |

| Alma mater | University of London (BSc, DSc) |

| Known for | |

| Spouse |

Mary Fanny Alexander Marshall

(m. 1877; died 1929) |

| Children | 12, including Oliver and Alexander |

| Relatives |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | University College Liverpool |

| Notable students | Charles Glover Barkla |

Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge (/ˈlɒdʒ/; 12 June 1851 – 22 August 1940) was an English physicist and inventor. He identified electromagnetic radiation independent of Hertz's proof and at his 1894 Royal Institution lectures ("The Work of Hertz and Some of His Successors"), Lodge demonstrated an early radio wave detector he named the coherer. In 1898 he was awarded the "syntonic" (or tuning) patent by the United States Patent Office. Lodge was Principal of the University of Birmingham from 1900 to 1920.

Lodge was also pioneer of spiritualism. His pseudoscientific research into life after death was a topic on which he wrote many books, including the best-selling Raymond; or, Life and Death (1916), which detailed messages he received from a medium, which he believed came from his son who was killed in the First World War.

Early life

[edit]Oliver Lodge was born in 1851 at 'The Views', Penkhull, a rural village near the Staffordshire Potteries in the northern part of Staffordshire[2] in what is now Stoke-on-Trent, and educated at Adams' Grammar School, Newport, Shropshire. His parents were Oliver Lodge (1826–1884) – later a ball clay merchant[note 1] at Wolstanton, Staffordshire – and his wife, Grace, née Heath (1826–1879).[citation needed] Lodge was their first child, and altogether they had eight sons and a daughter. Lodge's siblings included Sir Richard Lodge (1855–1936), historian; Eleanor Constance Lodge (1869–1936), historian and principal of Westfield College, London; and Alfred Lodge (1854–1937), mathematician.

When Lodge was 12, the family moved house to Wolstanton. At Moreton House on the southern tip of Wolstanton Marsh, he took over a large outbuilding for his first scientific experiments during the long school holidays.

In 1865, the 14-year-old Lodge left his schooling and joined his father's business (Oliver Lodge & Son) as an agent for B. Fayle & Co selling Purbeck blue clay to the pottery manufacturers. This work sometimes entailed him travelling as far as Scotland. He continued to assist his father until he reached the age of 22.

By the aged of 18, Lodge's father's growing wealth had enabled him to move his family to Chatterley House, Hanley. From there Lodge attended physics lectures in London, and also attended the Wedgwood Institute in nearby Burslem. At Chatterley House, just a mile south of Etruria Hall where Wedgwood had experimented, Lodge's Autobiography recalled that "something like real experimentation" began for him around 1869. His family moved again in 1875 – this time to the nearby Watlands Hall at the top of Porthill Bank between Middleport and Wolstanton (demolished 1951).

Academic research

[edit]Lodge obtained a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of London in 1875 and gained the title of Doctor of Science in 1877. At Wolstanton he experimented with producing a wholly new "electromagnetic light" in 1879 and 1880, paving the way for later experimental success. During this time, he also lectured at Bedford College, London.[3] Lodge left the Potteries in 1881 to up take the post of Professor of Physics and Mathematics at the newly founded University College, Liverpool.

In 1900 Lodge moved from Liverpool back to the Midlands and became the first principal of the new Birmingham University, remaining there until his retirement in 1919. He oversaw the start of the move of the university from Edmund Street in the city centre to its present Edgbaston campus. Lodge was awarded the Rumford Medal of the Royal Society in 1898, and was knighted in the 1902 Coronation Honours,[4] receiving the accolade from King Edward VII at Buckingham Palace on 24 October that year.[5] In 1928 he was made Freeman of his native city, Stoke-on-Trent.

Electromagnetism and radio

[edit]In 1873 J. C. Maxwell published A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism, and by 1876 Lodge was studying it intently. But Lodge was fairly limited in mathematical physics both by aptitude and training, and his first two papers were a description of a mechanism (of beaded strings and pulleys) that could serve to illustrate electrical phenomena such as conduction and polarization. Indeed, Lodge is probably best known for his advocacy and elaboration of Maxwell's aether theory – a later deprecated model postulating a wave-bearing medium filling all space. He explained his views on the aether in "Modern Views of Electricity" (1889) and continued to defend those ideas well into the twentieth century ("Ether and Reality", 1925).

As early as 1879, Lodge became interested in generating (and detecting) electromagnetic waves, something Maxwell had never considered. This interest continued throughout the 1880s, but some obstacles slowed Lodge's progress. First, he thought in terms of generating light waves with very high frequencies rather than radio waves with their much lower frequencies. Second, his good friend George FitzGerald (on whom Lodge depended for theoretical guidance) assured him (incorrectly) that "ether waves could not be generated electromagnetically."[6] FitzGerald later corrected his error, but, by 1881, Lodge had assumed a teaching position at University College, Liverpool the demands of which limited his time and his energy for research.

In 1887 the Royal Society of Arts asked Lodge to give a series of lectures on lightning, including why lightning rods and their conducting copper cable sometimes do not work, with lightning strikes following alternate paths, going through (and damaging) structures, instead of being conducted by the cables. Lodge took the opportunity to carry out a scientific investigation, simulating lightning by discharging Leyden jars into a long length of copper wire. Lodge found the charge would take a shorter high resistance route jumping a spark gap, instead of taking a longer low resistance route through a loop of copper wire. Lodge presented these first results, showing what he thought was the effect of inductance on the path lightning would take, in his May 1888 lecture.[7]

In other experiments that spring and summer, Lodge put a series of spark gaps along two 29 meter (95') long wires and noticed he was getting a very large spark in the gap near the end of the wires, which seemed to be consistent with the oscillation wavelength produced by the Leyden jar meeting with the wave being reflected at the end of the wire. In a darkened room, he also noted a glow at intervals along the wire at one half wavelength intervals. He took this as evidence that he was generating and detecting Maxwell's electromagnetic waves. While traveling on a vacation to the Tyrolean Alps in July 1888, Lodge read in a copy of Annalen der Physik that Heinrich Hertz in Germany had been conducting his own electromagnetic research, and that he had published a series of papers proving the existence of electromagnetic waves and their propagation in free space.[8][9] Lodge presented his own paper on electromagnetic waves along wires in September 1888 at the British Science Association meeting in Bath, England, adding a postscript acknowledging Hertz's work and saying: "The whole subject of electrical radiation seems working itself out splendidly."[7][10]

On 1 June 1894, at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science at Oxford University, Lodge gave a memorial lecture on the work of Hertz (recently deceased) and the German physicist's proof of the existence of electromagnetic waves 6 years earlier. Lodge set up a demonstration on the quasi optical nature of "Hertzian waves" (radio waves) and demonstrated their similarity to light and vision including reflection and transmission.[11] Later in June and on 14 August 1894 he did similar experiments, increasing the distance of transmission up to 55 meters (180').[7] Lodge used a detector called a coherer (invented by Edouard Branly), a glass tube containing metal filings between two electrodes. When the small electrical charge from waves from an antenna were applied to the electrodes, the metal particles would cling together or "cohere" causing the device to become conductive allowing the current from a battery to pass through it. In Lodge's setup the slight impulses from the coherer were picked up by a mirror galvanometer which would deflect a beam of light being projected on it, giving a visual signal that the impulse was received. After receiving a signal the metal filings in the coherer were broken apart or "decohered" by a manually operated vibrator or by the vibrations of a bell placed on the table near by that rang every time a transmission was received.[11] Since this was one year before Marconi's 1895 demonstration of a system for radio wireless telegraphy and contained many of the basic elements that would be used in Marconi's later wireless systems, Lodge's lecture became the focus of priority disputes with the Marconi Company a little over a decade later over invention of wireless telegraphy (radio). At the time of the dispute some, including the physicist John Ambrose Fleming, pointed out that Lodge's lecture was a physics experiment, not a demonstration of telegraphic signaling.[12] Lodge would later work with Alexander Muirhead on the development of devices specifically for wireless telegraphy.

In January 1898 Lodge presented a paper on "syntonic" tuning[13][14] which he received a patent for that same year.[15] Syntonic tuning allowed specific frequencies to be used by the transmitter and receiver in a wireless communication system. The Marconi Company had a similar tuning system adding to the priority dispute over the invention of radio. When Lodge's syntonic patent was extended in 1911 for another 7 years Marconi agreed to settle the patent dispute, purchasing the syntonic patent in 1912 and giving Lodge an (honorific) position as "scientific adviser".[12]

Other works

[edit]

In 1886 Lodge developed the moving boundary method for the measurement in solution of an ion transport number, which is the fraction of electric current carried by a given ionic species.[16]

Lodge carried out scientific investigations on the source of the electromotive force in the Voltaic cell, electrolysis, and the application of electricity to the dispersal of fog and smoke. [citation needed] He also made a major contribution to motoring when he patented a form of electric spark ignition for the internal combustion engine (the Lodge Igniter).[citation needed] Later, two of his sons developed his ideas and in 1903 founded Lodge Bros, which eventually became known as Lodge Plugs Ltd. He also made discoveries in the field of wireless transmission.[17] In 1898, Lodge gained a patent on the moving-coil loudspeaker, utilizing a coil connected to a diaphragm, suspended in a strong magnetic field.[18]

In political life, Lodge was an active member of the Fabian Society, and published two Fabian Tracts: Socialism & Individualism (1905), and Public Service versus Private Expenditure, co-authored with Sidney Webb, George Bernard Shaw and Sidney Ball. They invited him several times to lecture at the London School of Economics.[19]

In 1889 Lodge was appointed President of the Liverpool Physical Society, a position he held until 1893.[20] The society still runs to this day, though under a student body. In 1901, he was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society.[21]

Lodge was President of the British Association in 1912–1913.[22] In his 1913 Presidential Address to the Association, he affirmed his belief in the persistence of the human personality after death, the possibility of communicating with disembodied intelligent beings, and the validity of the Aether theory.[23]

Paranormal investigations

[edit]

Lodge is remembered for his studies in psychical research and spiritualism. He began to study psychical phenomena (chiefly telepathy) in the late 1880s, was a member of The Ghost Club, and served as president of the London-based Society for Psychical Research from 1901 to 1903. After his son, Raymond, was killed in World War I in 1915, he visited several mediums and wrote about the experience in a number of books, including the best-selling Raymond; or, Life and Death (1916).[24] Lodge was a friend of Arthur Conan Doyle, who also lost a son in World War I and was a Spiritualist.

Lodge was a Christian Spiritualist. In 1909, he published the book Survival of Man which expressed his belief that life after death had been demonstrated by mediumship. His most controversial book was Raymond or Life and Death (1916). The book documented the séances that he and his wife had attended with the medium Gladys Osborne Leonard. Lodge was convinced that his son Raymond had communicated with him and the book is a description of his son's experiences in the spirit world.[25] According to the book Raymond had reported that those who had died were still the same people that they had been on earth before they "passed over". There were houses, trees and flowers in the Spirit world, which was similar to the earthly realm, although there was no disease. The book also claimed that when soldiers died in World War I they had smoked cigars and received whisky in the spirit world and because of such statements the book was criticised.[26] Walter Cook wrote a rebuttal to Lodge, titled Reflections on Raymond (1917), that directly challenged Lodge's beliefs in Spiritualism.[27]

Although Lodge was convinced that Leonard's spirit control "Feda" had communicated with his son, he admitted a good deal of the information was nonsense and suggested that Feda picked it up from a séance sitter. Philosopher Paul Carus wrote that the "story of Raymond's communications rather excels all prior tales of mediumistic lore in the silliness of its revelations. But the saddest part of it consists in the fact that a great scientist, no less a one than Sir Oliver Lodge, has published the book and so stands sponsor for it."[28]

Scientific work on electromagnetic radiation convinced Lodge that an ether existed and that it filled the entire universe. Lodge came to believe that the spirit world existed in the ether. As a Christian Spiritualist, Lodge had written that the resurrection in the Bible referred to Christ's etheric body becoming visible to his disciples after the Crucifixion.[29] By the 1920s the physics of the ether had been undermined by the theory of relativity, however, Lodge still defended his ether theory arguing in "Ether and Reality" that it was not inconsistent with the theory of general relativity. Linked to his belief in Spiritualism, Lodge had also endorsed a theory of spiritual evolution which he promoted in Man and the Universe (1908) and Making of Man (1924).[30] He lectured on theistic evolution at the Charing Cross Hospital and at Christ Church, Westminster. His lectures were published in a book Evolution and Creation (1926).[31]

Historian Janet Oppenheim has noted that Lodge's interest in spiritualism "prompted some of his fellow scientists to wonder if his mind, too, had not been wrecked."[32] In 1913 the biologist Ray Lankester criticized the Spiritualist views of Lodge as unscientific and misleading the public.[33]

Edward Clodd criticized Lodge as being an incompetent researcher to detect fraud and claimed his Spiritualist beliefs were based on magical thinking and primitive superstition.[34] Charles Arthur Mercier (a leading British psychiatrist) wrote in his book Spiritualism and Sir Oliver Lodge (1917) that Lodge had been duped into believing mediumship by trickery and his Spiritualist views were based on assumptions and not scientific evidence.[35] Francis Jones in the American Journal of Psychology in a review for Lodge's The Survival of Man wrote that his psychical claims are not scientific and the book is one-sided as it does not contain research from experimental psychology.[36]

Magician John Booth noted that the stage mentalist David Devant managed to fool a number of people into believing he had genuine psychic ability who did not realize that his feats were magic tricks. At St. George's Hall, London he performed a fake "clairvoyant" act where he would read a message sealed inside an envelope. Lodge who was present in the audience was duped by the trick and claimed that Devant had used psychic powers. In 1936, Devant in his book Secrets of My Magic revealed the trick method he had used.[37]

Lodge had endorsed a clairvoyant medium known as "Annie Brittain". However, she made entirely incorrect guesses about a policeman who was disguised as a farmer. She was arrested and convicted for fraudulent fortune telling.[38] Joseph McCabe wrote a skeptical book on the Spiritualist beliefs of Lodge entitled The Religion of Sir Oliver Lodge (1914).[39]

Personal life

[edit]

Lodge married Mary Fanny Alexander Marshall at St George's Church, Newcastle-under-Lyme in 1877. They had twelve children, six boys and six girls, including Oliver William Foster, Alexander (Alec), Francis Brodie, Lionel and Noel. Four of his sons went into business using Lodge's inventions. Brodie and Alec created the Lodge Plug Company, which manufactured spark plugs for cars and aeroplanes. Lionel and Noel founded a company that produced an electrostatic device for cleaning factory and smelter smoke in 1913, called the Lodge Fume Deposit Company Limited (changed in 1919 to Lodge Fume Company Limited and in 1922, through agreement with the International Precipitation Corporation of California, to Lodge Cottrell Ltd). Oliver, the eldest son, became a poet and author.

After his retirement in 1920, Lodge and his wife settled in Normanton House, near Lake in Wiltshire, a few miles from Stonehenge.

Death

[edit]Lodge died, aged 89, died on 22 August. His wife Mary predeceased him in 1929. They are buried together at the local parish church, St. Michael's, Wilsford cum Lake.[40] Their eldest son Oliver and eldest daughter Violet are also buried at the church.

His obituary in The Times wrote:[41]

Always an impressive figure, tall and slender with a pleasing voice and charming manner, he enjoyed the affection and respect of a very large circle… Lodge's gifts as an expounder of knowledge were of a high order, and few scientific men have been able to set forth abstruse facts in a more lucid or engaging form… Those who heard him on a great occasion, as when he gave his Romanes lecture at Oxford or his British Association presidential address at Birmingham, were charmed by his alluring personality as well as impressed by the orderly development of his thesis. But he was even better in informal debate, and when he rose, the audience, however perplexed or jaded, settled down in a pleased expectation that was never disappointed.

Lodge archives

[edit]Lodge's letters and papers were divided after his death. Some were deposited at the University of Birmingham and University of Liverpool and others at the Society for Psychical Research and the University College London. Lodge was long-lived and a prolific letter writer and other letters of his survive in the personal papers of other individuals and several other universities and other institutions. Among the known collections of his papers are the following:

- The University of Birmingham Special Collections holds over 2000 items of Lodge's correspondence relating to family, co-workers at Birmingham and Liverpool Universities and also from numerous religious, political and literary figures. The collection also includes a number of Lodge's diaries, photographs and newscuttings relating to his scientific research and scripts of his published work. There are also an additional 212 letters of Lodge which have been acquired over the years (1881–1939).

- The University of Liverpool holds some notebooks and letters of Oliver Lodge and also has a laboratory named after him, the main administrative centre of the Physics Department where the majority of lecturers and researchers have their offices.

- University College London Special Collections hold 1991 items of Lodge's correspondence between 1871 and 1938.

- The Society for Psychical Research holds 2710 letters written to Oliver Lodge.

- Devon Record Office holds Lodge's letters to Sir Thomas Acland (1907–1908).

- The University of Glasgow Library holds Lodge's letters to William Macneile Dixon (1900–1938).

- The University of St Andrews has twenty-three letters from Lodge to Wilfrid Ward (1896–1908).

- Trinity College Dublin is custodian of Lodge's correspondence with John Joly.

- Imperial College, London Archives hold nineteen letters Lodge wrote to his fellow scientist, Silvanus Thompson.

- The London Science Museum holds an early notebook of Oliver Lodge's dated 1880, correspondence dating from 1894 to 1913 and a paper on atomic theory.

Published works

[edit]Lodge wrote more than 40 books, about the afterlife, aether, relativity, and electromagnetic theory.

- Modern Views of Electricity, 1889

- Pioneers of Science, 1893

- The Work of Hertz and Some of His Successors, 1894 (after Signalling Through Space Without Wires, 1900)

- Modern Views on Matter, 1903

- Electric Theory of Matter. Harper's Magazine. 1904. (O'Neill's Electronic Museum)

- "Mind and Matter": A Criticism of Professor Haeckel, 1904

- Life and Matter, 1905

- Public Service versus Private Expenditure, co-authored with Sidney Webb, 1905

- The Substance of Faith Allied With Science. A Catechism for Parents and Teachers, 1907

- Electrons, or The Nature and Properties of Negative Electricity, 1907

- Man and the Universe, Methuen, London, 1908

- Science and Immortality, New York, Moffat, Yard and Co., 1908.

- Survival of Man, 1909

- The Ether of Space, May, 1909.[42] ISBN 1-4021-8302-X (paperback), ISBN 1-4021-1766-3 (hardcover)

- Reason and Belief, 1910. Book Tree. February 2000. ISBN 1-58509-226-6

- Modern Problems, 1912

- Science and Religion, 1914

- The war and after; short chapters on subjects of serious practical import for the average citizen from A.D. 1915 onwards, 1915

- Raymond or Life and Death, 1916

- Christopher, 1918

- Raymond Revised, 1922

- The Making of Man, 1924

- Of Atoms and Rays, 1924

- Ether and Reality, 1925. ISBN 0-7661-7865-X

- Relativity – A very elementary exposition. Paperback. Methuen & Co. Ltd. London. 11 June 1925

- Talks About Wireless, 1925

- Ether, Encyclopædia Britannica, Thirteenth Edition, 1926

- Evolution and Creation, 1926

- Science and Human Progress, 1927

- Modern Scientific Ideas. Benn's Sixpenny Library No. 101, 1927

- Why I Believe in Personal Immortality, 1928

- Phantom Walls, 1929

- Beyond Physics, or The Idealization of Mechanism, 1930

- The Reality of a Spiritual World, 1930

- Conviction of Survival, 1930

- Advancing Science, 1931

- Past Years: An Autobiography. 1931 Hodder and Stoughton Ltd, London, 1930; Charles Scribner & Sons, 1932; Cambridge University Press, 2012

- Letters from Sir Oliver Lodge, psychical, religious, scientific and personal, London, Cassell and Company, Ltd

- My Philosophy, 1933

Legacy

[edit]

Lodge received the honorary Doctor of Laws (LL.D) from the University of Glasgow in June 1901.[43]

Oliver Lodge Primary School in Vanderbijlpark, South Africa is named in his honour.

Lodge is commemorated in Liverpool with a bronze figure entitled Education, at the base of the Queen Victoria Monument and the Oliver Lodge Building which houses the physics department of the University of Liverpool.[44][45]

See also

[edit]- Notable relatives of Oliver Lodge

- Samuel Lodge, clergyman & author (uncle)

- Alfred Lodge, mathematician (brother)

- Sir Richard Lodge, historian (brother)

- Eleanor Constance Lodge, historian (sister)

- Alexander Lodge, inventor (son)

- Oliver W F Lodge, poet and author (son)

- Percy John Heawood, mathematician (cousin)

- Carron O Lodge, artist (cousin)

- George Edward Lodge, artist (cousin)

- Francis Graham Lodge, artist (second cousin)

- Tom Lodge, author & radio broadcaster (grandson)

- Fiona Godlee, physician and editor (great-granddaughter)

- David Trotman, mathematician (great-grandson)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Purbeck Blue Clay, as it was then known, according to "History Page". Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 5 August 2008..

References

[edit]- ^ Gregory, R. A.; Ferguson, A. (1941). "Oliver Joseph Lodge. 1851-1940". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 3 (10): 550. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1941.0022. S2CID 154552517.

- ^ "Sir Oliver Lodge's Birthplace, Penkhull". Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ Lodge, Oliver. "Biography of Oliver Lodge". PSI Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "The Coronation Honours". The Times. No. 36804. London. 26 June 1902. p. 5.

- ^ "No. 27494". The London Gazette. 11 November 1902. p. 7165.

- ^ Hunt, Bruce J. (2005) The Maxwellians, Cornell University Press, page 37, ISBN 0801482348.

- ^ a b c James P. Rybak, Oliver Lodge: Almost the Father of Radio Archived 3 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, page 4, from Antique Wireless

- ^ Robert P. Crease, The Great Equations: Breakthroughs in Science from Pythagoras to Heisenberg, W. W. Norton & Company - 2008, page 146

- ^ Bruce J. Hunt, The Alternative Path: Lodge, Lightning, and Electromagnetic Waves, Making Waves: Oliver Lodge and the Cultures of Science, 1875-1940

- ^ Rowlands, Peter (1990) Oliver Lodge and the Liverpool Physics Society. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0853230277.

- ^ a b Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, MIT Press, 2001, pages 30–32

- ^ a b Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, MIT Press, 2001, page 48

- ^ summarized in "Dr. Lodge on wireless telegraphy". Electrical Review. 42 (1053). The Electrical Review, Ltd.: 103–104 28 January 1898. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ Sungook Hong, Wireless: From Marconi's Black-box to the Audion, page 92

- ^ British patent GB189711575 Lodge, O. J. Improvements in Syntonized Telegraphy without Line Wires filed: May 10, 1897, granted: August 10, 1898

- ^ Laidler K.J. and Meiser J.H., Physical Chemistry (Benjamin/Cummings 1982) p.276-280 ISBN 0-8053-5682-7

- ^ Regal, Brian. (2005). Radio: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood. p. 21. ISBN 0-313-33167-7

- ^ Lodge, (1898). British Patent 9,712/98.

- ^ Jolly, W. P. (1975). Sir Oliver Lodge. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0838617038

- ^ Peter Rowlands (1990). Oliver Lodge and the Liverpool Physical Society. Liverpool University Press. pp. 48–57. ISBN 978-0-85323-027-4.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ The Presidential Address to the British Association for 1913 by Oliver Lodge (at the meeting held in Birmingham, England)

- ^ "Address to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, delivered at Birmingham, 1913, by Principal Sir Oliver Lodge, F.R.S., President". The Athenaeum (4481): 257–258. 13 September 1913.

- ^ Brown, Callum G. (2006). Religion and Society in Twentieth-Century Britain. Longman. p. 104. ISBN 978-0582472891

- ^ Kollar, Rene (2000). Searching for Raymond. Lexington Books. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-0739101612

- ^ Byrne, Georgina (2010) Modern Spiritualism and the Church of England, 1850–1939. Boydell Press. pp. 75–79. ISBN 978-1843835899

- ^ Emden, Richard (2012). The Quick and the Dead. Bloomsbury Paperbacks. p. 201. ISBN 978-1408822456

- ^ Carus, Paul. (1917). Sir Oliver Lodge on Life After Death. The Monist, Vol. 27, No. 2. pp. 316–319.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J. (2001). Reconciling Science and Religion: The Debate in Early-Twentieth-Century Britain. University Of Chicago Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0226068589

- ^ Bowler, Peter J. (2009). Science For All: The Popularization of Science in Early Twentieth-Century. University Of Chicago Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0226068633

- ^ The Bookman: A Review of Books and Life. Volume 64. Dodd, Mead. 1926. p. 104.

- ^ Oppenheim, Janet (1988). The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850–1914. Cambridge University Press. p. 376. ISBN 978-0739101612.

- ^ Bowler, Peter J. (2001). Reconciling Science and Religion: The Debate in Early-Twentieth-Century Britain. University Of Chicago Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0226068589

- ^ The Question: A Brief History and Examination of Modern Spiritualism. Grant Richards, London. 1917. pp. 265–301.

- ^ Spiritualism and Sir Oliver Lodge. London: Mental Culture Enterprise. 1917.

- ^ Jones, Francis (1910). "The Survival of Man: A Study in Unrecognized Human Faculty by Oliver Lodge". The American Journal of Psychology. 21 (3): 505.

- ^ Booth, John. (1986). Psychic Paradoxes. Prometheus Books. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0879753580

- ^ Taylor, J. Danforth. (1920). Psychical Research and the Physician. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 182: 610–612.

- ^ McCabe, Joseph. (1914). The Religion of Sir Oliver Lodge. Watts & Co.

- ^ For a photo of his gravesite, see "Sir Oliver Joseph Lodge". Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2008.

- ^ Obituary in The Times, Friday 23 August 1940 (page 7, column 4)

- ^ "Review of The Ether of Space by Sir Oliver Lodge". Nature. 82 (2097): 271. 6 January 1910. Bibcode:1910Natur..82..271.. doi:10.1038/082271b0. hdl:2027/uc1.$c187656. S2CID 3965243.

- ^ "Glasgow University Jubilee". The Times. No. 36481. London. 14 June 1901. p. 10. Retrieved 5 January 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Queen Victoria Monument The Victorian Web

- ^ AccessAble The Oliver Lodge Building

Further reading

[edit]- Walter Cook. (1917). Reflections on "Raymond". London: Grant Richards.

- Edward Clodd, Arthur Conan Doyle. (1917). Is Sir Oliver Lodge Right? Yes. By A. Conan Doyle. No. By Edward Clodd. The Strand Magazine. Volume 54, July to December. pp. 49–54.

- J. Arthur Hill. (1932). Letters from Sir Oliver Lodge: Psychical, Religious, Scientific and Personal. Cassell and Company.

- Steve Hoffmaster. (1986). Sir Oliver Lodge and the Spiritualists. In Kendrick Frazier. Science Confronts the Paranormal. Prometheus Books. pp. 79–87.

- Paul Hookham. (1917). Raymond: A Rejoinder Questioning The Validity of Certain Evidence and of Sir Oliver Lodge's Conclusions Regarding It. B. H. Blackwell.

- W. P. Jolly. (1974). Sir Oliver Lodge: Psychical Researcher and Scientist. London: Constable.

- Alfred W. Martin. (1918). Psychic Tendencies of To-Day, An Exposition and Critique of New Thought, Christian Science, Spiritualism, Psychical Research (Sir Oliver Lodge) and Modern Materialism in Relation to Immortality. D. Appleton and Company.

- Walter Mann. (1919). The Follies and Frauds of Spiritualism. Rationalist Association. London: Watts & Co.

- Joseph McCabe. (1914). The Religion of Sir Oliver Lodge. London: Watts & Co.

- Joseph McCabe. (1905). Sir Oliver Lodge on Haeckel. The Hibbert Journal 3: 741–755.

- Charles Arthur Mercier. (1917). Spiritualism and Sir Oliver Lodge. London: Mental Culture Enterprise.

- James Mussell & Graeme Gooday (Eds) A Pioneer of Connection: Recovering the Life and Work of Oliver Lodge (University of Pittsburgh, 2020)

- Frank Podmore. (1910). The Survival of Man by Sir Oliver Lodge. The Hibbert Journal 8: 669–672.

External links

[edit]- Works by Oliver Lodge at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Oliver Lodge at the Internet Archive

- Works by Oliver Lodge at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Painted portrait of Sir Oliver Lodge by Sir George Reid at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Interactive Java Tutorial – Lodge's experiment demonstrating the first tunable radio receiver National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

- U.S. patent 609,154, "Electric Telegraphy" (wireless telegraphy using Ruhmkorff coil for transmitter and Branly coherer for detector, the "syntonic" tuning patent) August 1898. Sold to Marconi in 1912.

- "Oliver Joseph Lodge, Sir: 1851 – 1940". Adventures in CyberSound.

- Death of Sir Oliver Lodge – Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Vol. 34, pages 435 – 436.

- "Sir Oliver Lodge Archived 29 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine 1851–1940". First Spiritual Temple. 2001.

- University of Birmingham Staff Papers: Papers of Sir Oliver Lodge

- The Potteries Museum & Art Gallery, in Stoke-on-Trent, UK, features a display about local hero Oliver Lodge and his pioneering 1907 igniter, forerunner of the spark plug.

- A collection of portraits of Sir Oliver Lodge at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Lodge-Cottrell Ltd

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- 1851 births

- 1940 deaths

- Alumni of the University of London

- Academics of the University of Liverpool

- British acoustical engineers

- English inventors

- English physicists

- English spiritualists

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- History of radio technology

- Knights Bachelor

- Members of the Fabian Society

- British parapsychologists

- People educated at Adams' Grammar School

- People from Penkhull

- Presidents of the Physical Society

- Vice-chancellors of the University of Birmingham

- Burials in Wiltshire