Bekonscot

View over site in 2008 | |

| Established | 1920s |

|---|---|

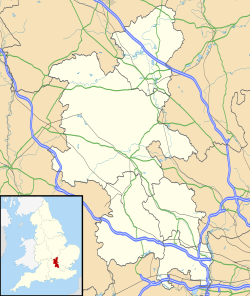

| Location | Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, UK |

| Coordinates | 51°36′49″N 0°38′41″W / 51.61361°N 0.64472°W |

| Type | Miniature park |

| Founder |

|

| Website | bekonscot |

Bekonscot Model Village and Railway is a model village built in the 1920s in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, UK at a scale of one inch to one foot. It portrays aspects of England mostly dating from the 1930s and contains several fictitious villages featuring replicas of notable local buildings. The model railway has almost 10 scale miles (400 m) of tracks and in 2001, a 7 1/4 in gauge railway was opened to transport visitors. Bekonscot has become both a popular tourist location and a part of English culture. It is commonly referred to as the oldest surviving model village in the UK and by 2020, had received over 14 million visitors. Authors such as Enid Blyton, Mary Norton and Will Self have been inspired by the village.

Creation

[edit]Bekonscot Model Village and Railway was created as a private miniature park in the 1920s by Roland Callingham and his gardener W. A. Berry.[1]: 661 [2][3] Callingham's wife had told him to take his model railway hobby outside their house, so he purchased four acres of land in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, and built an ideal English village with a church, railway and high street, illuminated by electric lights. Everything was constructed at a scale of one inch to one foot.[4][3] The railway was 1,200 feet (366 m) long and had stations including a London terminus called Maryloo (referencing real stations Marylebone and Waterloo). It was designed by Wenman Joseph Bassett-Lowke, who had also provided a train set made out of silver to the Maharaja of Gwalior.[5][1]: 652 It was opened to the general public in 1929 and three years later it had become a popular tourist attraction. By 1933, it was opened to the public every Sunday between April and September with the railway running and every Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday afternoon without the trains working. The entrance fee was donated to the Railway Benevolent Institution and the Queen's Institute of District Nursing.[6][3][4]

History

[edit]In 1934, Bekonscot was visited by the young Elizabeth II on her eighth birthday.[7][1]: 661 An article published in the National Geographic in 1937 praised the "flawless miniatures of wood and stone, metal, stucco, bright paint, and glass".[1]: 649 Bekonscot, alongside Pendon Museum in Oxfordshire and Bourton-on-the-Water in Gloucestershire, inspired a trend for model villages in British seaside resort towns such as Babbacombe, Southport and Southsea.[8] By the 1960s it was owned and run by the Bekonscot Model Railway and Charitable Association.[2] It is commonly referred to as the oldest surviving model village in the UK, although the eccentric Charles Paget Wade constructed a village called Fladbury at his home Snowshill Manor in 1907, which has been restored by National Trust volunteers.[9][10]

Bekonscot was updated with recent developments such as Concorde and office buildings until the 1990s, when it was returned to the 1930s. By 2020, it had incorporated a new town and added a replica of High and Over, a house designed by Amyas Connell in the nearby town of Amersham.[5] The project is now composed of the fictitious villages of Bekonscot, Evenlode new town and colliery, Epwood, Greenhaily, Hanton, Southpool and Splashyng, which are linked together by the model railway. It features replicas of some notable local buildings and contains features such as an airport, a cable car, a cathedral, a castle, a cricket match, pubs, windmills and a zoo.[1]: 652 [7][11][12][13] The zoo is named Chessnade after Chessington World of Adventures and Whipsnade Zoo; shops are titled with punning names, such as the butcher Sam and Ella, the dressmaker Miss A. Stitch, the florist Dan D. Lyon and the greengrocer Chris P. Lettis.[13]: 3 [12]

The model railway now has almost 10 scale miles (400 m) of tracks, with twelve stations and over 3,000 shrubs and trees. Trains run on a 1 gauge track and are powered by electricity.[13]: 9 [7] Visitors walk through the model village and can also look down on it from different viewing spots.[14]: 53 In 2001, the Bekonscot Light Railway (BLR) was opened as a 7 1/4 in gauge railway which moves visitors around the village. The entire project closes over winter; smaller models are taken indoors, whilst larger buildings and the railway are refurbished on site.[13]: 23, 25

In popular culture

[edit]

Bekonscot is the oldest participant in the International Association of Miniature Parks (IMAP).[14]: 36 By 2020, Bekonscot had received over 14 million visitors and had become part of English culture.[5][14]: 37 The village frequently appears on lists of recommended family days out.[4][15][16] It represents an idealised version of traditional English villages and its brochure states it is a "little piece of history that is forever England".[14]: 36 [17] Enid Blyton was a Beaconsfield resident and friend of Callingham; she set her short story "The Enchanted Village" in Bekonscot.[7][12] The Sunday Telegraph reported that Toyland, where her fictional character Noddy lives, was inspired by Bekonscot.[18] In tribute to Blyton, a replica of her now demolished house Green Hedges was installed in 1997.[7][12] Mary Norton was inspired by Bekonscot when she wrote The Borrowers Aloft and Will Self set his short story "Scale" in the model village.[5] Bekonscot also features in the non-fiction book Dreamstreets: A Journey Through Britain's Village Utopias.[19] Historian Tim Dunn grew up nearby and has written the official guidebook.[20]

See also

[edit]- Bollocks to Alton Towers - a book about alternative days out in the UK which features Bekonscot

- Madurodam - a Dutch model village

- Tucktonia - a model village in Christchurch, Dorset which closed down in 1986

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Brown, Andrew H.; Stewart, B. Anthony (May 1937). "Bekonscot, England's toy-sized town". National Geographic.

- ^ a b McFadden, Dorothy Loa (March 1969). "It's a small world". The Rotarian. Rotary International. p. 55. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ a b c "A dream village come true". Bucks Examiner. 14 April 1933. p. 6. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Swanborough, Nicola (7 September 2002). "Family outing to Bekonscot model village". The Times. "Gale IF0501536388.

- ^ a b c d Bratby, Richard (23 July 2020). "Model villages aren't just for kids". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ "Beaconsfield". Buckinghamshire Advertiser. 24 March 1933. p. 7. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Roy, Anita (September 2008). "Little Englander". Outlook Traveller. Outlook Publishing. pp. 65–66. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Matless, David; Short, Brian; Gilbert, David (1 January 2003). "Afterword: Emblematic Landscapes of the British Modern". Geographies of British Modernity: 250–257. doi:10.1002/9780470752258.after. ISBN 9780470752258.

- ^ Aling, Mike (2021). "Backgarden Worldbuilding: The Architecture of the Model Village" (PDF). Architectural Design. 91 (3): 112–119. doi:10.1002/ad.2700. S2CID 233545764. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ "Model village brought back to life in Cotswolds". BBC News. 15 April 2018. Archived from the original on 15 March 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ "Just for Fun – Bekonscot Model Village". BBC. Archived from the original on 18 September 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Walsh, Richard (2017). "Complexity, Scale, Story: Narrative Models in Will Self and Enid Blyton" (PDF). Insights. 10 (6). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Dunn, Tim (2009). Bekonscot – Historic Model Village & Railway. Norwich, UK: Jarrold Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85101-435-7.

- ^ a b c d Padan, Yael (2017). Modelscapes of nationalism: Collective memories and future visions. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789089649850.

- ^ "Family-Friendly Things To Do Within An Hour Of London". Londonist. 3 May 2022. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Richings, James (14 August 2021). "Beaconsfield's model village is named as one of the best attractions in the UK – Do you agree?". Bucks Free Press. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Froud, Daisy (November 2004). "Thinking Beyond the Homely: Countryside Properties and the Shape of Time". Home Cultures. 1 (3): 211–233. doi:10.2752/174063104778053473. S2CID 144797776.

- ^ Bray, Paul (22 February 2009). "A walker's paradise". Sunday Telegraph. p. 119. Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ Yallop, Jacqueline (23 February 2016). "Book Review: Dreamstreets: A Journey Through Britain's Village Utopias by Jacqueline Yallop". LSE Review of Books. LSE. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (3 August 2004). "Model village that is forever England". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 March 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

External links

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Bailey, Liam (2006). Forever England: Photographs from Bekonscot model village. Stockport, UK: Dewi Lewis. ISBN 9781904587309.

- Bekonscot Model Railway and Charitable Association (1972). Bekonscot model village. Norwich, UK: Jarrold. OCLC 497820473.

- Parfitt, Ida (1962). Bekonscot Model Village, Beaconsfield, Bucks. Beaconsfield, UK: Bekonscot Model Railway & General Charitable Association. OCLC 48678414.