Magadhan Empire

Magadhan Empire | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 544 BC – 28 BC 320 AD – 550 AD | |||||||||||||

Expansion of the Magadhan Empire between 6th and 4th century BCE | |||||||||||||

The Magadha Empire under various dynasties | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Rajagriha (Girivraj) Later, Pataliputra (modern-day Patna) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Sanskrit[1] Magadhi Prakrit Ardhamagadhi Prakrit | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Brahmanism (later Hinduism) Buddhism Jainism | ||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Māgadhī | ||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy[a] | ||||||||||||

| Notable emperors | |||||||||||||

• c. 544 – c. 492 BCE | Bimbisara | ||||||||||||

• c. 492 – c. 460 BCE | Ajatashatru | ||||||||||||

• c. 413 – c. 395 BCE | Shishunaga | ||||||||||||

• c. 345 – c. 329 BCE | Mahapadma Nanda | ||||||||||||

• c. 329 – c. 321 BCE | Dhana Nanda | ||||||||||||

• c. 321 – c. 297 BCE | Chandragupta Maurya | ||||||||||||

• c. 268 – c. 232 BCE | Ashoka | ||||||||||||

• c. 185 – c. 149 BCE | Pushyamitra Shunga | ||||||||||||

• c. 319 – c. 335 CE | Chandragupta I | ||||||||||||

• c. 335 – c. 375 CE | Samudragupta | ||||||||||||

• c. 375 – c. 415 CE | Chandragupta II | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Panas | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||

The Magadhan Empire was an ancient Indian empire that succeeded the Magadha Mahajanapada. It was established by Bimbisara[2] in 544 BC. It was ruled by the Haryankas (544–413 BCE), the Shaishunagas (413–345 BCE), the Nandas (345–322 BCE), the Mauryas (322–184 BCE), the Śungas (184–73 BCE), the Kanvas (73–28 BCE) and the Guptas (320–550 CE).[3]

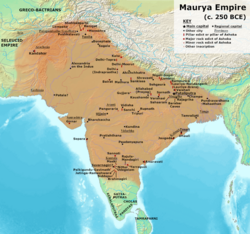

Under the Mauryas, Magadha became a pan-Indian empire, covering large swaths of the Indian subcontinent and Afghanistan. The Kanva dynasty lost much of its territory after being defeated by the Satavahanas of Deccan in 28 BCE and was reduced to a small principality around Pataliputra.[4][5] Under the Guptas, Magadha emerged once again as the preeminent power in India.

History

[edit]

The Haryanka dynasty was founded by Bimbisara. Bimbisara led an active and expansive policy, conquering the kingdom of Anga in what is now West Bengal. King Bimbisara was killed by his son, Ajatashatru. Pasenadi, king of neighbouring Kosala and brother-in-law of Bimbisara, promptly reconquered the Kashi province.

Accounts differ slightly as to the cause of King Ajatashatru's war with the Licchavi, a powerful tribe north of the river Ganges. It appears that Ajatashatru sent a minister to the area who worked for three years to undermine the unity of the Licchavis. To launch his attack across the Ganges River, Ajatashatru built a fort at the town of Pataliputra. Torn by disagreements, the Licchavis fought with Ajatashatru. It took fifteen years for Ajatashatru to defeat them. Jain texts tell how Ajatashatru used two new weapons: a catapult, and a covered chariot with swinging mace that has been compared to a modern tank. Pataliputra began to grow as a centre of commerce and became the capital of Magadha after Ajatashatru's death.

The Haryanka dynasty was overthrown by the Shishunaga dynasty. The last Shishunaga ruler, Mahanandin, was assassinated by Mahapadma Nanda in 345 BCE, the first of the so-called "Nine Nandas", i. e. Mahapadma and his eight sons, last being Dhana Nanda.

In 326 BCE, the army of Alexander approached the western boundaries of Magadha. The army, exhausted and frightened at the prospect of facing another giant Indian army at the Ganges, mutinied at the Hyphasis (the modern Beas River) and refused to march further east. Alexander, after the meeting with his officer Coenus, was persuaded that it was better to return and turned south, conquering his way down the Indus to the Ocean.

Around 321 BCE, the Nanda Dynasty ended with the defeat of Dhana Nanda at the hands of Chandragupta Maurya who became the first king of the Mauryan Empire with the help of his mentor Chanakya. The Empire later extended over most of India under King Ashoka The Great, who was at first known as 'Ashoka the Cruel' but later became a disciple of Buddhism and became known as 'Dharma Ashoka'.[6][7] Later, the Mauryan Empire ended, as did the Shunga and Khārabēḷa empires, to be replaced by the Gupta Empire. The capital of the Gupta Empire remained Pataliputra in Magadha.

During the Pala-period in Magadha from the 11th to 13th century CE, a local Buddhist dynasty known as the Pithipatis of Bodh Gaya ruled as tributaries to Pala Empire.[8]

Under Mauryan dynasty (322 BCE – 185 BCE)

[edit]Chandragupta Maurya

[edit]After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, Chandragupta led a series of campaigns in 305 BCE to take satrapies in the Indus Valley and northwest India.[9] When Alexander's remaining forces were routed, returning westwards, Seleucus I Nicator fought to defend these territories. Not many details of the campaigns are known from ancient sources. Seleucus was defeated and retreated into the mountainous region of Afghanistan.[10]

Chandragupta established a strong centralised state with an administration at Pataliputra, which, according to Megasthenes, was "surrounded by a wooden wall pierced by 64 gates and 570 towers". Aelian, although not expressly quoting Megasthenes nor mentioning Pataliputra, described Indian palaces as superior in splendor to Persia's Susa or Ecbatana.[11] The architecture of the city seems to have had many similarities with Persian cities of the period.[12]

Chandragupta renounced his throne and followed Jain teacher Bhadrabahu. He is said to have lived as an ascetic at Shravanabelagola for several years before fasting to death, as per the Jain practice of sallekhana.

Bindusara Maurya

[edit]Bindusara's life has not been documented as well as that of his father Chandragupta or of his son Ashoka. Chanakya continued to serve as prime minister during his reign. According to the medieval Tibetan scholar Taranatha who visited India, Chanakya helped Bindusara "to destroy the nobles and kings of the sixteen kingdoms and thus to become absolute master of the territory between the eastern and western oceans". During his rule, the citizens of Taxila revolted twice. The reason for the first revolt was the maladministration of Susima, his eldest son. The reason for the second revolt is unknown, but Bindusara could not suppress it in his lifetime. It was crushed by Ashoka after Bindusara's death.[13]

Bindusara maintained friendly diplomatic relations with the Hellenic world. Deimachus was the ambassador of Seleucid king Antiochus I at Bindusara's court.[14] Diodorus states that the king of Palibothra (Pataliputra, the Mauryan capital) welcomed a Greek author, Iambulus. This king is usually identified as Bindusara.[14] Pliny states that the Ptolemaic king Philadelphus sent an envoy named Dionysius to India.[15][16] According to Sailendra Nath Sen, this appears to have happened during Bindusara's reign.

Unlike his father Chandragupta (who at a later stage converted to Jainism), Bindusara believed in the Ajivika religion.

Ashoka Maurya

[edit]As emperor he was ambitious and aggressive, re-asserting the Empire's superiority in southern and western India. But it was his conquest of Kalinga (262–261 BCE) which proved to be the pivotal event of his life. Ashoka used Kalinga to project power over a large region by building a fortification there and securing it as a possession.[17] Although Ashoka's army succeeded in overwhelming Kalinga forces of royal soldiers and citizen militias, an estimated 100,000 soldiers and civilians were killed in the furious warfare, including over 10,000 of Imperial Mauryan soldiers. Hundreds of thousands of people were adversely affected by the destruction and fallout of war.

The Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, are found throughout the Subcontinent. Ranging from as far west as Afghanistan and as far south as Andhra (Nellore District), Ashoka's edicts state his policies and accomplishments. Although predominantly written in Prakrit, two of them were written in Greek, and one in both Greek and Aramaic. Ashoka's edicts refer to the Greeks, Kambojas, and Gandharas as peoples forming a frontier region of his empire. They also attest to Ashoka's having sent envoys to the Greek rulers in the West as far as the Mediterranean. The edicts precisely name each of the rulers of the Hellenistic world at the time such as Amtiyoko (Antiochus II Theos), Tulamaya (Ptolemy II), Amtikini (Antigonos II), Maka (Magas) and Alikasudaro (Alexander II of Epirus) as recipients of Ashoka's proselytism. The Edicts also accurately locate their territory "600 yojanas away" (1 yojana being about 7 miles), corresponding to the distance between the center of India and Greece (roughly 4,000 miles).[18]

Dynasties and rulers

[edit]There is much uncertainty about the succession of kings and the precise chronology of Magadha prior to Mahapadma Nanda; the accounts of various ancient texts (all of which were written many centuries later than the era in question) contradict each other on many points.

Two notable rulers of Magadha were Bimbisara (also known as Shrenika) and his son Ajatashatru (also known as Kunika), who are mentioned in Buddhist and Jain literature as contemporaries of the Buddha and Mahavira. Later, the throne of Magadha was usurped by Mahapadma Nanda, the founder of the Nanda Dynasty (c. 345 – c. 322 BCE), which conquered much of north India. The Nanda dynasty was overthrown by Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Maurya Empire (c. 322–185 BCE).

Furthermore, there is a "Long Chronology" and a contrasting "Short Chronology" preferred by some scholars, an issue that is inextricably linked to the uncertain chronology of the Buddha and Mahavira.[19] According to historian K. T. S. Sarao, a proponent of the Short Chronology wherein the Buddha's lifespan was c.477–397 BCE, it can be estimated that Bimbisara was reigning c.457–405 BCE, and Ajatashatru was reigning c.405–373 BCE.[20] According to historian John Keay, a proponent of the "Long Chronology," Bimbisara must have been reigning in the late 5th century BCE,[21] and Ajatashatru in the early 4th century BCE.[22] Keay states that there is great uncertainty about the royal succession after Ajatashatru's death, probably because there was a period of "court intrigues and murders," during which "evidently the throne changed hands frequently, perhaps with more than one incumbent claiming to occupy it at the same time" until Mahapadma Nanda was able to secure the throne.[22]

List of rulers

[edit]The following "Long Chronology" is according to the Buddhist Mahavamsa:[23]

- Haryanka dynasty (c. 544 – 413 BCE)

| Ruler | Reign (BCE) |

|---|---|

| Bimbisara | 544–491 BCE |

| Ajatashatru | 491–461 BCE |

| Udayin | 461–428 BCE |

| Anirudha | 428–419 BCE |

| Munda | 419–417 BCE |

| Darshaka | 417–415 BCE |

| Nāgadāsaka | 415–413 BCE |

- Shishunaga dynasty (c. 413 – 345 BCE)

| Ruler | Reign (BCE) |

|---|---|

| Shishunaga | 413–395 BCE |

| Kalashoka | 395–377 BCE |

| Kshemadharman | 377–365 BCE |

| Kshatraujas | 365–355 BCE |

| Nandivardhana | 355–349 BCE |

| Mahanandin | 349–345 BCE |

- Nanda Empire (c. 345 – c. 322 BCE)

| Ruler | Reign (BCE) |

|---|---|

| Mahapadma Nanda | 345–340 BCE |

| Pandhukananda | 340–339 BCE |

| Panghupatinanda | 339–338 BCE |

| Bhutapalananda | 338–337 BCE |

| Rashtrapalananada | 337–336 BCE |

| Govishanakananda | 336–335 BCE |

| Dashasidkhakananda | 335–334 BCE |

| Kaivartananda | 334–333 BCE |

| Karvinathanand | 333–330 BCE |

| Dhana Nanda | 330–322 BCE |

Other lists

[edit]The Hindu Literature mostly Puranas give a different sequence:[24]

- Shishunaga dynasty (360 years)

- Shishunaga (reigned for 40 years)

- Kakavarna (36 years)

- Kshemadharman (20 years)

- Kshatraujas (29 years)

- Bimbisara (28 years)

- Ajatashatru (25 years)

- Darbhaka or Darshaka or Harshaka (25 years)

- Udayin (33 years)

- Nandivardhana (42 years)

- Mahanandin (43 years)

- Nanda dynasty (100 years)

- List by Jain literature

A shorter list appears in the Jain tradition, which simply lists Shrenika (Bimbisara), Kunika (Ajatashatru), Udayin, followed by the Nanda dynasty.[24]

Notes

[edit]- ^ as described in the Arthashastra

References

[edit]- ^ Jain, Dhanesh (2007). "Sociolinguistics of the Indo-Aryan languages". In George Cardona; Dhanesh Jain (eds.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 47–66, 51. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- ^ Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. p. 114. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

Thus the foundation of the Magadhan empire laid by Bimbisara was now firmly established as a result of the subtle diplomacy of Ajatasatru .

- ^

- J. L. Jain (1994). Development and Structure of an Urban System. Mittal Publications. p. 28. ISBN 978-81-7099-552-4.

The sceptre of Magadhan empire was borne successively by the Sisunagas, the Nandas, the Mauryas, the Shungas and the Kanvas from early fifth century B.C. to the first century B.C.

- Narendra Krishna Sinha (1973). A History of India. Orient Longman. p. 107.

Later in the fourth century A.D., with the rise of the second Magadhan Empire under the Guptas,

- J. L. Jain (1994). Development and Structure of an Urban System. Mittal Publications. p. 28. ISBN 978-81-7099-552-4.

- ^ Keny, Liladhar (1943). ""THE SUPPOSED IDENTIFICATION OF UDAYANA OF KAUŚĀMBI WITH UDAYIN OF MAGADHA"". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 24 (1/2): 60–66. JSTOR 41784405.

- ^ Roy, Daya (1986). "SOME ASPECTS OF THE RELATION BETWEEN ANGA AND MAGADHA (600 B.C.—323 B.C.)". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 47: 108–112. JSTOR 44141530.

- ^ Tenzin Tharpa, Tibetan Buddhist Essentials: A Study Guide for the 21st Century: Volume 1: Introduction, Origin, and Adaptation, p.31

- ^ Sanjeev Sanyal (2016), The Ocean of Churn: How the Indian Ocean Shaped Human History, section "Ashoka, the not so great"

- ^ Balogh, Daniel (2021). Pithipati Puzzles: Custodians of the Diamond Throne. British Museum Research Publications. pp. 40–58. ISBN 9780861592289.

- ^ From Polis to Empire, the Ancient World, C. 800 B.C.-A.D. 500. Greenwood Publishing. 2002. ISBN 0313309426. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Kistler, John M. (2007). War Elephants. University of Nebraska Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0803260047. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "In the royal residences in India where the greatest of the kings of that country live, there are so many objects for admiration that neither Memnon's city of Susa with all its extravagance, nor the magnificence of Ectabana is to be compared with them. ... In the parks, tame peacocks and pheasants are kept." Aelian, Characteristics of animals book XIII, Chapter 18, also quoted in The Cambridge History of India, Volume 1, p411

- ^ Romila Thapar (1961), Aśoka and the decline of the Mauryas, Volume 5, p.129, Oxford University Press. "The architectural closeness of certain buildings in Achaemenid Iran and Mauryan India have raised much comment. The royal palace at Pataliputra is the most striking example and has been compared with the palaces at Susa, Ecbatana, and Persepolis."

- ^ Eugène Burnouf (1911). Legends of Indian Buddhism. New York: E. P. Dutton. p. 59.

- ^ a b S. N. Sen 1999, p. 142.

- ^ "Three Greek ambassadors are known by name: Megasthenes, ambassador to Chandragupta; Deimachus, ambassador to Chandragupta's son Bindusara; and Dyonisius, whom Ptolemy Philadelphus sent to the court of Ashoka, Bindusara's son", McEvilley, p.367

- ^ India, the Ancient Past, Burjor Avari, pp. 108–109

- ^ Allchin, F. R.; Erdosy, George (1995). The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 306.

- ^ Edicts of Ashoka, 13th Rock Edict, translation S. Dhammika.

- ^ Bechert, Heinz (1995). When Did the Buddha Live?: The Controversy on the Dating of the Historical Buddha. Sri Satguru Publications. p. 129. ISBN 978-81-7030-469-2.

- ^ Sarao, K. T. S. (2003), "The Ācariyaparamparā and Date of the Buddha.", Indian Historical Review, 30 (1–2): 1–12, doi:10.1177/037698360303000201, S2CID 141897826

- ^ Keay, John (2011). India: A History. Open Road + Grove/Atlantic. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-8021-9550-0.

- ^ a b Keay, John (2011). India: A History. Open Road + Grove/Atlantic. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8021-9550-0.

- ^ Bechert, Heinz (1995). When Did the Buddha Live?: The Controversy on the Dating of the Historical Buddha. Sri Satguru Publications. ISBN 978-81-7030-469-2.

- ^ a b Geiger, Wilhelm; Bode, Mabel Haynes (25 August 1912). "Mahavamsa : the great chronicle of Ceylon". London : Pub. for the Pali Text Society by Oxford Univ. Pr. – via Internet Archive.

Sources

[edit]- Raychaudhuri, H.C. (1972). Political History of Ancient India. Calcutta: University of Calcutta.

- Law, Bimala Churn (1926). "4. The Magadhas". Ancient Indian Tribes. Lahore: Motilal Banarsidas.

- Bronkhorst, Johannes (2007). Greater Magadha: studies in the culture of early India (PDF). Handbook of oriental studies. Section two, India. Vol. 19. Leiden; Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15719-4. ISSN 0169-9377. OCLC 608455986. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 September 2015.

- Singh, Upinder (2016), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson, ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9