Churchill River (Atlantic)

| Churchill River | |

|---|---|

Churchill River and waterfalls, Labrador | |

| Native name | Mishtashipu (Innu) |

| Location | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Newfoundland and Labrador |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Smallwood Reservoir, Labrador |

| • elevation | 466 m (1,529 ft) |

| Mouth | |

• location | Atlantic Ocean |

| Length | 856 km (532 mi) |

| Basin size | 79,800 km2 (30,800 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 1,620 m3/s (57,210 cu ft/s)[citation needed] |

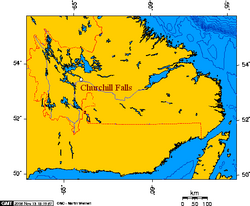

The Churchill River, formerly known by other names, is a river in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. It flows east from the Smallwood Reservoir into the Atlantic Ocean via Lake Melville. The river is 856 km (532 mi) long and drains an area of 79,800 km2 (30,800 sq mi), making it the longest river in Atlantic Canada.

Names

[edit]The Innu name of the river is Mishtashipu[1] or Mishta-shipu ("Grand River") among the Labrador Innu and Patshishetshuanau-shipu ("Churchill Falls River") among the Central Innu, the Labrador Métis (NunatuKavut), and Nunatsiavut.[citation needed] The latter name was formerly calqued into English as the Grand River, the name commonly used by locals.

In 1821, Captain William Martin of HM brig Clinker renamed the river the Hamilton River after the then-current commodore-governor of Newfoundland Charles Hamilton. The name gradually supplanted use of the Grand River before being replaced on 1 February 1965 by provincial premier Joey Smallwood. Smallwood renamed it the "Churchill River" after the former British prime minister Winston Churchill ahead of the beginning of construction on the river's major hydroelectric project.

In 2022, MHA Perry Trimper called for Churchill's name to be removed from the river in favour of either "Grand River" or its Innu name.[2]

Geography

[edit]

The river flows in an arc, first north from Ashuanipi Lake though the saucer-shaped Labrador Plateau,[3][4] and then mainly east through a series of lakes.[5] Several of these lakes have been flooded to create the Smallwood Reservoir.[6] The river then flows through a rocky canyon which is hundreds of feet deep, over Churchill Falls, and through a series of rapids below the falls.[7] The water flow in the canyon has been mainly diverted underground through a giant hydroelectric power generating plant.[8] The river continues eastward until it flows into Lake Melville.

Hydroelectric projects

[edit]Churchill Falls is the site of a major hydroelectric project, which diverted almost all of the stream that once fell over Churchill Falls. It presently has a capacity of 5,428 MW and other slated hydroelectric plants on the river will bring the total to over 9,200 MW. The Churchill Falls development has become a source of friction between two Canadian provinces, as Newfoundland and Labrador asserts that Quebec's Hydro-Québec (despite having provided a major part of the financing and access to the North American power grid) has taken a disproportionate share of the development's profits. Hydro-Québec still buys power from the dam at rates established in the 1969 power purchase agreement.[8]

U-boat

[edit]In 2012 divers using side scan sonar found what they believe is the wreck of a U-boat just downstream of Muskrat Falls, validating a local legend.[9] However, examination of historical records shows this to be unlikely, and the sonar images were quite grainy.[10]

See also

[edit]- Churchill River (Hudson Bay)

- List of longest rivers of Canada

- List of rivers of Newfoundland and Labrador

References

[edit]- ^ "Churchill River". Canadian Geographic. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

- ^ @MikeConnors (4 May 2022). "Perry Trimper is calling on the province to work with the Innu Nation to rename the Churchill River to its original…" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Andrew Hempstead (3 July 2017). Moon Newfoundland & Labrador. Avalon Publishing. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-63121-571-1.

- ^ Robert Bourassa (1985). Power from the North. Prentice-Hall Canada Incorporated. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-13-688367-8.

- ^ Fernando de Mello Vianna (17 June 1979). The International Geographic Encyclopedia and Atlas. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-349-05002-4.

- ^ María Jesús Hernáez Lerena (18 September 2015). Pathways of Creativity in Contemporary Newfoundland and Labrador. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-4438-8333-7.

- ^ J. Paxton (22 December 2016). The Statesman's Year-Book 1975-76. Springer. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-230-27104-3.

- ^ a b James R. Penn; Larry Allen (2001). Rivers of the World: A Social, Geographical, and Environmental Sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-57607-042-0.

- ^ Brennan, Richard J. (26 July 2012). "German U-boat wreck may be at bottom of Churchill River in Labrador". Toronto Star. Retrieved 31 March 2016.

- ^ "Group on mission to prove there is truth in legends that Nazi submarines went far inland from Canadian coast". National Post, Tristin Hopper, April 19, 2013

Further reading

[edit]

- Low, Albert Peter (1896), "Report on explorations in the Labrador peninsula along the East Main, Koksoak, Hamilton, Manicuagan and portions of other rivers in 1892-93-94-95", Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa: Queen's Printer, retrieved 2010-09-13

External links

[edit]- Canadian Council for Geographic Education page with a series of articles on the history of the Churchill River Archived 2013-09-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Churchill River (Labrador)". The Canadian Encyclopedia.