History of pseudoscience

The history of pseudoscience is the study of pseudoscientific theories over time. A pseudoscience is a set of ideas that presents itself as science, while it does not meet the criteria to properly be called such.[1][2]

Distinguishing between proper science and pseudoscience is sometimes difficult. One popular proposal for demarcation between the two is the falsification criterion, most notably contributed to by the philosopher Karl Popper. In the history of pseudoscience it can be especially hard to separate the two, because some sciences developed from pseudosciences. An example of this is the science chemistry, which traces its origins from the protoscience of alchemy.

The vast diversity in pseudosciences further complicates the history of pseudoscience. Some pseudosciences originated in the pre-scientific era, such as astrology and acupuncture. Others developed as part of an ideology, such as Lysenkoism, or as a response to perceived threats to an ideology. An example of this is creationism, which was developed as a response to the scientific theory of evolution.

Despite failing to meet proper scientific standards, many pseudosciences survive. This is usually due to a persistent core of devotees who refuse to accept scientific criticism of their beliefs, or due to popular misconceptions. Sheer popularity is also a factor, as is attested by astrology which remains popular despite being rejected by a large majority of scientists.[3][4][5][6]

19th century

[edit]

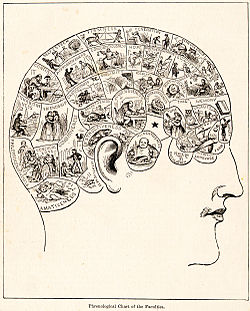

Among the most notable developments in the history of pseudoscience in the 19th century are the rise of Spiritualism (traced in America to 1848), homeopathy (first formulated in 1796), and phrenology (developed around 1800). Another popular pseudoscientific belief that arose during the 19th century was the idea that there were canals visible on Mars. A relatively mild Christian fundamentalist backlash against the scientific theory of evolution foreshadowed subsequent events in the 20th century.

The study of bumps and fissures in people's skulls to determine their character, phrenology, was originally considered a science. It influenced psychiatry and early studies into neuroscience.[7] As science advanced, phrenology was increasingly viewed as a pseudoscience. Halfway through the 19th century, the scientific community had prevailingly abandoned it,[8] although it was not comprehensively tested until much later.[9]

Halfway through the century, iridology was invented by the Hungarian physician Ignaz von Peczely.[10] The theory would remain popular throughout the 20th century as well.[11]

Spiritualism (sometimes referred to as "Modern Spiritualism" or "Spiritism")[12] or "Modern American Spiritualism"[13] grew phenomenally during the period. The American version of this movement has been traced to the Fox sisters who in 1848 began claiming the ability to communicate with the dead.[14] The religious movement would remain popular until the 1920s, when renowned magician Harry Houdini began exposing famous mediums and other performers as frauds (see also Harry Houdini#Debunking spiritualists). While the religious beliefs of Spiritualism are not presented as science, and thus are not properly considered pseudoscientific, the movement did spawn numerous pseudoscientific phenomena such as ectoplasm and spirit photography.

The principles of homeopathy were first formulated in 1796, by German physician Samuel Hahnemann. At the time, mainstream medicine was a primitive affair and still made use of techniques such as bloodletting. Homeopathic medicine by contrast consisted of extremely diluted substances, which meant that patients basically received water. Compared to the damage often caused by conventional medicine, this was an improvement.[15] During the 1830s homeopathic institutions and schools spread across the US and Europe.[16] Despite these early successes, homeopathy was not without its critics.[17] Its popularity was on the decline before the end of the 19th century, though it has been revived in the 20th century.

The supposed Martian canals were first reported in 1877, by the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli. The belief in them peaked in the late 19th century, but was widely discredited in the beginning of the 20th century.

The publication of Atlantis: The Antediluvian World by politician and author Ignatius L. Donnelly in 1882, renewed interest in the ancient idea of Atlantis. This highly advanced society supposedly existed several millennia before the rise of civilizations like Ancient Egypt. It was first mentioned by Plato, as a literary device in two of his dialogues. Other stories of lost continents, such as Mu and Lemuria also arose during the late 19th century.

In 1881 the Dutch Vereniging tegen de Kwakzalverij (English: Society against Quackery) was formed to oppose pseudoscientific trends in medicine. It is still active.

20th century

[edit]Among the most notable developments to pseudoscience in the 20th century are the rise of Creationism, the demise of Spiritualism, and the first formulation of ancient astronaut theories.

Reflexology, the idea that an undetectable life force connects various parts of the body to the feet and sometimes the hands and ears, was introduced in the US in 1913 as 'zone therapy'.[18][19]

Creationism arose during the 20th century as a result of various other historical developments. When the modern evolutionary synthesis overcame the eclipse of Darwinism in the first half of the 20th century, American fundamentalist Christians began opposing the teaching of the theory of evolution in public schools. They introduced numerous laws to this effect, one of which was notoriously upheld by the Scopes Trial. In the second half of the century the Space Race caused a renewed interest in science and worry that the USA was falling behind on the Soviet Union. Stricter science standards were adopted and led to the re-introduction of the theory of evolution in the curriculum. The laws against teaching evolution were now ruled unconstitutional, because they violated the separation of church and state. Attempting to evade this ruling, the Christian fundamentalists produced a supposedly secular alternative to evolution, Creationism. Perhaps the most influential publication of this new pseudoscience was The Genesis Flood by young earth creationists John C. Whitcomb and Henry M. Morris.

The dawn of the space age also inspired various versions of ancient astronaut theories. While differences between the specific theories exists, they share the idea that intelligent extraterrestrials visited Earth in the distant past and made contact with then living humans. Popular authors, such as Erich von Däniken and Zecharia Sitchin, began publishing in the 1960s. Among the most notable publications in the genre is Chariots of the Gods?, which appeared in 1968.

Late in the 20th century several prominent skeptical foundations were formed to counter the growth of pseudosciences. In the US, the most notable of these are, in chronological order, the Center for Inquiry (1991), The Skeptics Society (1992), the James Randi Educational Foundation (1996), and the New England Skeptical Society (1996). The Committee for Skeptical Inquiry, which has similar goals, had already been founded in 1976. It became part of the Center for Inquiry as part of the foundation of the latter in 1991. In the Netherlands Stichting Skepsis was founded in 1987.

21st century

[edit]At the beginning of the 21st century, a variety of pseudoscientific theories remain popular and new ones continue to crop up.

The Flat Earth is the idea that the Earth is flat. It is believed to have existed for thousands of years, but studies show this is a relatively new theory that begun in the 1990s when the internet starting up allowed such ideas to spread much quicker.

Creationism, in the form of Intelligent Design, suffered a major legal defeat in the Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District trial. Judge John E. Jones III ruled that Intelligent Design is inseparable from Creationism, and its teaching in public schools violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. The trial sparked much interest, and was the subject of several documentaries including the award-winning NOVA production Judgment Day: Intelligent Design on Trial (2007).

The pseudoscientific idea that vaccines cause autism originated in the 1990s, but became prominent in the media during the first decade of the 21st century. Despite a broad scientific consensus against the idea that there is a link between vaccination and autism,[20][21][22][23][24] several celebrities have joined the debate. Most notable of these is Jenny McCarthy, whose son has autism. In February 2009, surgeon Andrew Wakefield, who published the original research supposedly indicating a link between vaccines and autism, was reported to have fixed the data by The Sunday Times.[25] A hearing by the General Medical Council began in March 2007, examining charges of professional misconduct. On 24 May 2010, he was struck off the United Kingdom medical register, effectively banning him from practicing medicine in Britain.

The most notable development in the ancient astronauts genre was the opening of Erich von Däniken's Mystery Park in 2003. While the park had a good first year, the number of visitors was much lower than the expected 500,000 a year. This caused financial difficulties, which led to the closure of the park in 2006.[26]

See also

[edit]Histories of specific pseudosciences

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Pseudoscientific - pretending to be scientific, falsely represented as being scientific", from the Oxford American Dictionary, published by the Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ The Skeptic's Dictionary entry on 'Pseudoscience'

- ^ Humphrey Taylor. "The Religious and Other Beliefs of Americans 2003". Archived from the original on 2007-01-11. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ "Science and Technology: Public Attitudes and Understanding". National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on 2015-08-18. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ^ "Astrology". Encarta. Microsoft. 2008. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

Scientists have long rejected the principles of astrology, but millions of people continue to believe in or practice it.

- ^ Astrology: Fraud or Superstition? by Chaz Bufe "Astrology Fraud or Superstition". See Sharp Press.

- ^ Simpson, D. (2005) "Phrenology and the neurosciences: contributions of F. J. Gall and J. G. Spurzheim" ANZ Journal of Surgery. Oxford. Vol. 75.6; p. 475

- ^ Phrenology: An Overview, by dr. John van Wyhe

- ^ Parker Jones, O., Alfaro-Almagro, F., & Jbabdi, S. (2018). "An empirical, 21st century evaluation of phrenology". Cortex. Volume 106. pp. 26–35. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2018.04.011

- ^ The Skeptic's Dictionary entry on 'Iridology'

- ^ Iridology Is Nonsense, by Stephen Barrett, M.D.

- ^ Podmore, Frank (1903). "Modern Spiritualism. A History and a Criticism". The American Journal of Psychology. 14 (1). University of Illinois Press: 116–117. doi:10.2307/1412224. hdl:2027/iau.31858027158827. JSTOR 1412224.

- ^ Britten, Emma Hardinge (1870). Modern American Spiritualism.

- ^ The Skeptic's Dictionary entry on 'Spiritualism'

- ^ Ernst E, Kaptchuk TJ (1996). "Homeopathy revisited". Arch. Intern. Med. 156 (19): 2162–64. doi:10.1001/archinte.156.19.2162. PMID 8885813.

- ^ Winston, Julian (2006). "Homeopathy Timeline". The Faces of Homoeopathy. Whole Health Now. Archived from the original on 2018-12-15. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ Example of a contemporary criticism of homeopathy: John Forbes (1846). Homeopathy, allopathy and young physic. London.

- ^ Reflexology: A Close Look, by Stephen Barrett, M.D.

- ^ The Skeptic's Dictionary entry on 'Reflexology'

- ^ European Medicines Agency (2004-03-24). "EMEA Public Statement on Thiomersal in Vaccines for Human Use" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2007-07-22.

- ^ National Advisory Committee on Immunization (2007). "Thimerosal: updated statement. An Advisory Committee Statement". Can Commun Dis Rep. 33 (ACS-6): 1–13. PMID 17663033.

- ^ American Medical Association (2004-05-18). "AMA Welcomes New IOM Report Rejecting Link Between Vaccines and Autism". Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ American Academy of Pediatrics (2004-05-18). "What Parents Should Know About Thimerosal". Archived from the original on 2007-07-08. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ Vaccines & Autism: Myths and Misconceptions Archived 2014-10-07 at the Wayback Machine by Steven Novella, M.D., for the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry

- ^ Deer, Brian (2009-02-08). "MMR doctor Andrew Wakefield fixed data on autism". London: The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 2010-05-25. Retrieved 2009-02-08.

- ^ Closure of Mystery Park in Interlaken is no mystery Archived 2008-12-12 at the Wayback Machine by swissinfo.ch