Casey Stengel

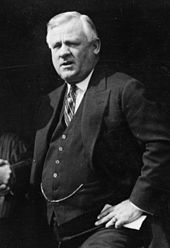

Charles Dillon "Casey" Stengel (/ˈstɛŋɡəl/; July 30, 1890 – September 29, 1975) was an American Major League Baseball right fielder and manager, best known as the manager of the championship New York Yankees of the 1950s and later, the expansion New York Mets. Nicknamed "the Ol' Perfessor", he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966.

Stengel was born in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1890. In 1910, he began a professional baseball career that would span over half a century. After almost three seasons in the minor leagues, Stengel reached the major leagues late in 1912, as an outfielder, for the Brooklyn Dodgers. His six seasons there saw some success, among them playing for Brooklyn's 1916 National League championship team, but he also developed a reputation as a clown. After repeated clashes over pay with the Dodgers owner, Charlie Ebbets, Stengel was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1918; however, he enlisted in the Navy that summer, for the remainder of World War I. After returning to baseball, he continued his pay disputes, resulting in trades to the Philadelphia Phillies (in 1919) and to the New York Giants (in 1921). There, he learned much about baseball from the manager, John McGraw, and had some of the glorious moments in his career, such as hitting an inside-the-park home run in Game 1 of the 1923 World Series to defeat the Yankees. His major league playing career ended with the Boston Braves in 1925, but he then began a career as a manager.

The first twenty years of Stengel's second career brought mostly poor finishes, especially during his MLB managerial stints with the Dodgers (1934–1936) and Braves (1938–1943). He thereafter enjoyed some success on the minor league level, and Yankee general manager George Weiss hired him as manager in October 1948. Stengel's Yankees won the World Series five consecutive times (1949–1953), the only time that has been achieved. Although the team won ten pennants in his twelve seasons, and won seven World Series, his final two years brought less success, with a third-place finish in 1959, and a loss in the 1960 World Series. By then aged 70, he was dismissed by the Yankees shortly after the defeat.

Stengel had become well known for his humorous and sometimes disjointed way of speech during his time with the Yankees, and these skills of showmanship served the expansion Mets well when they hired him in late 1961. He promoted the team tirelessly, as well as managing it to a 40–120 win–loss record, the most losses of any 20th century MLB team. The team finished last all four years he managed it, but was boosted by considerable support from fans. Stengel retired in 1965, and became a fixture at baseball events for the rest of his life. Although Stengel is sometimes described as one of the great managers in major league history, others have contrasted his success during the Yankee years with his lack of success at other times, and concluded he was a good manager only when given good players. Stengel is remembered as one of the great characters in baseball history.

Early life

[edit]Charles Dillon Stengel was born on July 30, 1890, in Kansas City, Missouri. His ancestry included German and Irish; his parents—Louis Stengel and Jennie (Jordan) Stengel—were from the Quad Cities area of Illinois and Iowa, and had moved to Kansas City soon after their 1886 wedding so Louis could take an insurance job. "Charlie" was the youngest of three children, and the second son. Charlie Stengel played sandlot baseball as a child, and also played baseball, football and basketball at Kansas City's Central High School. His basketball team won the city championship, while the baseball team won the state championship.[1][2][3]

As a teenager, Stengel played on a number of semipro baseball teams.[4] He played on the traveling team called the Kansas City Red Sox during the summers of 1908 and 1909, going as far west as Wyoming and earning a dollar a day. He was offered a contract by the minor league Kansas City Blues for $135 a month, more money than his father was making. Since young Stengel was underage, his father had to agree, which he did. Louis Stengel recalled, "So I put down my paper and signed. You could never change that boy's mind anyway".[5]

Playing career

[edit]Minor leagues

[edit]

Before reporting to spring training for the Blues in early 1910 at Excelsior Springs, Missouri, Stengel was approached by his neighbor, Kid Nichols, a former star pitcher, who advised him to listen to his manager and to the older players, and if he was minded to reject their advice, at least think it over for a month or so first.[6] Stengel failed to make the ball club, which was part of the American Association, considered one of the top minor leagues. Kansas City optioned Stengel to the Kankakee Kays of the Class D Northern Association, a lower-level minor league, to gain experience as an outfielder. He had a .251 batting average with Kankakee when the league folded in July. He found a place with the Shelbyville Grays, who moved mid-season and became the Maysville Rivermen, of the Class D Blue Grass League, batting .221.[1][7] He returned to the Blues for the final week of the season, with his combined batting average for 1910 at .237.[8]

I want to thank my parents for letting me play baseball, and I'm thankful I had baseball knuckles and couldn't become a dentist.

Uncertain of whether he would be successful as a baseball player, Stengel attended Western Dental College in the 1910–1911 offseason. He would later tell stories of his woes as a left-handed would-be dentist using right-handed equipment. The Blues sold Stengel to the Aurora Blues of the Class C Wisconsin–Illinois League. He led the league with a .352 batting average. Brooklyn Dodgers scout Larry Sutton took a trip from Chicago to nearby Aurora, noticed Stengel, and the Dodgers purchased his contract on September 1, 1911. Brooklyn outfielder Zach Wheat later claimed credit for tipping off Sutton that Stengel was worth signing. Stengel finished the season with Aurora and returned to dental school for the offseason.[1][10]

The Dodgers assigned Stengel to the Montgomery Rebels of the Class A Southern Association for the 1912 season. Playing for manager Kid Elberfeld, Stengel batted .290 and led the league in outfield assists. He also developed a reputation as an eccentric player. Scout Mike Kahoe referred to Stengel as a "dandy ballplayer, but it's all from the neck down".[1] After reporting to Brooklyn in September and getting a taste of the big leagues, he spent a third offseason at dental school in 1912–1913. He did not graduate, though whenever his baseball career hit a bad patch in the years to follow, his wife Edna would urge him to get his degree.[11]

Brooklyn years (1912–1917)

[edit]They brought me up to the Brooklyn Dodgers, which at that time was in Brooklyn.

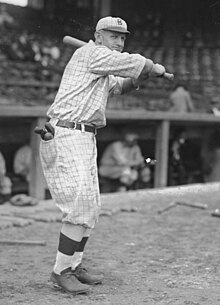

In later years, Casey Stengel told stories of his coming to Brooklyn to play for the Dodgers; most focused on his naïveté and were, at least, exaggerated.[13] Wheat was from the Kansas City area and watched over Stengel, getting the young player a locker next to his and working with him on outfield technique.[14] Stengel made his MLB debut at Brooklyn's Washington Park on September 17, 1912, as the starting center fielder,[1] and went 4–4 with a walk, two stolen bases and two tie-breaking runs batted in, leading seventh-place Brooklyn to a 7–3 win over the Pirates.[15][16] Stengel continued to play well, finishing the season with a .316 batting average, though hitting .351 when right-handers started against Brooklyn and only .250 when left-handers started.[17]

After holding out for better pay, Stengel signed with the Dodgers for 1913. He won the starting center fielder job. The Dodgers had a new ballpark, Ebbets Field, and Stengel became the first person to hit a home run there, first an inside-the-park home run against the New York Yankees in an exhibition game to open the stadium, and then in the regular season. During the 1913 season, Stengel acquired the nickname "Casey"; there are varying stories of how this came to be, though his home town of Kansas City likely played a prominent role—sportswriter Fred Lieb stated that the ballplayer had "Charles Stengel—K.C." stenciled on his bags. Although he missed 25 games with injuries, he hit .272 with seven official home runs in his first full season as a major leaguer. Prior to 1914 spring training, Stengel coached baseball at the University of Mississippi. Though the position was unpaid, he was designated an assistant professor for the time he was there, something that may have been the source of Stengel's nickname, "The Ol' Perfessor".[18][19]

The Dodgers were an improving team in Stengel's first years with them, and he was greatly influenced by the manager who joined the team in 1914, Wilbert Robinson.[20] Stengel also avoided a holdout in 1914; Dodgers owner Charlie Ebbets was anxious to put his players under contract lest they jump to the new Federal League, and nearly doubled Stengel's salary to $4,000 per year.[21] During spring training, the Dodgers faced the minor league Baltimore Orioles and their rookie, Babe Ruth, who pitched. Ruth hit a triple over Stengel's head but gave up two doubles to him, and Stengel chased down a long Ruth fly ball to right in the Dodgers' loss. Both Brooklyn and Stengel started the season slowly, but both recovered with a hot streak that left the Dodgers only 4 games under .500, their best record since 1903, and Stengel finished with a .316 batting average,[22] fifth best in the league. His on-base percentage led the league at .404, though this was not yet an official statistic.[23] With the Federal League still active, Stengel was rewarded with a two-year contract at $6,000 per year.[24]

Stengel reported to spring training ill and thin; he was unable to work out for much of the time the Dodgers spent in Florida. Although the team stated that he had typhoid fever, still common in 1915, Lieb wrote after Stengel's death in 1975 that the ballplayer had gonorrhea. Stengel may have been involved in a well-known incident during spring training when Robinson agreed to catch a baseball dropped from an airplane piloted by Ruth Law—except that it proved not to be a baseball, but a small grapefruit, much to the manager's shock, as he assumed the liquid on him was blood. Law stated that she dropped the grapefruit as she had forgotten the baseball, but Stengel retold the story, imitating Robinson, many times in his later years, with himself as grapefruit dropper, and is often given the credit for the stunt.[25] Stengel's batting average dipped as low as the .150s for part of the season; though he eventually recovered to .237, this was still the worst full season percentage of his major league career.[1]

Soon after the 1916 season started, it became clear that the Dodgers were one of the better teams in the league.[26] Robinson managed to squeeze one more year of productivity out of some older veterans such as Chief Meyers, who said of Stengel, "It was Casey who kept us on our toes. He was the life of the party and just kept all us old-timers pepped up all season."[27] Stengel, mostly playing right field, hit .279 with eight home runs, one less than the team leader in that category, Wheat. Stengel's home run off Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander, who won 33 games that year, in the second game of a doubleheader on September 30, provided the margin of victory as the Dodgers went into first place to stay, qualifying for their first World Series, against the Boston Red Sox.[27] Despite getting two hits in a Game 1 loss at Boston, Stengel was benched for Game 2 because the Red Sox were pitching a left-hander, Babe Ruth, and Stengel hit better against right-handers.[28] Stengel, back in the lineup for Game 3, got a hit in Brooklyn's only victory of the series. He was benched again in Game 4 against left-hander Dutch Leonard, though he was inserted as a pinch runner, and got another hit in the Game 5 loss, finishing 4 for 11, .364, the best Dodger batting average of the Series.[29]

Despite the successful season, Ebbets was determined to cut his players' salaries, including Stengel, whom he considered overpaid. By then, the Federal League was defunct, and the reserve clause prevented players from jumping to other major league clubs. The owner sent Stengel a contract for $4,600, and when that was rejected, cut it by another $400. A holdout ensued, together with a war of words waged in the press. With little leverage, Stengel became willing to sign for the original contract, and did on March 27, 1917, but missed most of spring training.[30] Stengel's batting average dropped from .279 to .257 as the defending league champion Dodgers finished seventh in the eight-team league, but he led the team in games, hits, doubles, triples, home runs and runs batted in. After the season, Ebbets sent Stengel a contract for $4,100, and the outfielder eventually signed for that amount, but on January 9, 1918, Ebbets traded him along with George Cutshaw to the Pittsburgh Pirates for Burleigh Grimes, Al Mamaux and Chuck Ward.[1][31]

Pittsburgh and Philadelphia (1918–1921)

[edit]The Pirates had been the only National League team to do worse than the Dodgers in 1917, finishing last.[32] Stengel met with the Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss to seek a salary increase, but found Dreyfuss reluctant to deal until Stengel proved himself as a Pirate. On June 3, 1918, Stengel was ejected for arguing with the umpire, and was fined by the league office for taking off his shirt on the field. The U.S. had been fighting in World War I for a year, and Stengel enlisted in the Navy. His wartime service was playing for and managing the Brooklyn Navy Yard's baseball team, driving in the only run to beat Army, 1–0, before 5,000 spectators at the Polo Grounds. He also occasionally helped paint a ship—he later stated he had guarded the Gowanus Canal, and not a single submarine got into it.[33]

I had many years that I was not so successful as a ball player, as it is a game of skill.

The Armistice renewed the conflict between Stengel and Dreyfuss, and the outfielder held out again to begin the 1919 season. Both wanted to see Stengel traded, but no deal was immediately made.[35] By then, Stengel's position as regular right fielder had been taken by Billy Southworth, and he had difficulty breaking back into the lineup.[36] Stengel played better than he had before he enlisted, and by the time Dreyfuss traded him to the Philadelphia Phillies for Possum Whitted on August 9, he was batting .293 with four home runs.[1][37] But before being traded, Stengel pulled one of his most famous stunts, on May 25 at Ebbets Field, as a member of the visiting Pirates. It was not unusual at Ebbets Field for right fielders of either team, rather than go to the dugout after three were out, to go to the Dodgers' bullpen, in foul territory down the right field line, if they were not likely to bat in the upcoming inning. Stengel did so to visit old friends, and discovered that pitcher Leon Cadore had captured a sparrow. Stengel took it, and quietly placed it under his cap when called to bat in the sixth inning. He received mixed boos and cheers from the Brooklyn crowd as a former Dodger, took a deep bow at the plate, and doffed his cap, whereupon the bird flew away to great laughter from the crowd.[38]

The trade to the Phillies ended Stengel's major league season for 1919, as he refused to report unless he got a raise, and when one was not forthcoming, returned to Kansas City to raise a barnstorming team.[39] In the offseason, he came to terms with William Baker, the owner of the Phillies, and hit .292 in 1920 with nine home runs. However, racked by injuries and no longer young for a ballplayer, he did not play much in the early part of the 1921 season. On June 30, 1921, the Phillies traded Stengel, Red Causey and Johnny Rawlings to the New York Giants for Lee King, Goldie Rapp and Lance Richbourg.[40][41] The Giants were one of the dominant teams in the National League, and Stengel, who had feared being sent to the minor leagues, quietly placed a long-distance call once informed to ensure he was not the victim of a practical joke.[42]

New York Giants and Boston Braves (1921–1925)

[edit]I learned more from McGraw than anybody.

When Stengel reported to the Giants on July 1, 1921, they were managed, as they had been for almost 20 years, by John McGraw. Stengel biographer Robert W. Creamer said of McGraw, "his Giants were the most feared, the most respected, the most admired team in baseball".[44] Stengel biographer Marty Appel noted, "McGraw and Stengel. Teacher and student. Casey was about to learn a lot about managing".[45] Stengel had time to learn, playing in only 18 games for the Giants in 1921, mostly as a pinch hitter,[43] and watched from his place on the bench as McGraw led the Giants from a 71⁄2 game deficit on August 24 to the National League pennant.[46] Although he was on the 25-player postseason roster,[47] Stengel did not appear in the 1921 World Series against the Yankees, as McGraw used only 13 players (4 of them pitchers) in beating the Yankees, five games to three.[48] The only contribution Stengel made to the box score was being ejected from Game 5 for arguing.[49]

McGraw brought several outfielders into spring training with the Giants. When Stengel was not included with the starters when the manager split the squad, some sportswriters assumed he would not be with the team when the regular season began. Stengel, at McGraw's request, acted as a coach to the young players on the "B" squad, and worked hard, getting key hits in spring training games, and making the Giants as a reserve outfielder. McGraw and Stengel sometimes stayed up all night, discussing baseball strategy. With two Giant outfielders injured by June, Stengel was put in center field, and hit .368 in 84 games, as McGraw platooned him against right-handers. If Stengel had enough plate appearances to qualify for the league batting championship, he would have finished second to Rogers Hornsby of the St. Louis Cardinals, who hit .401.[1][49][50] The Giants played the Yankees again in the 1922 World Series; Stengel went 1–4 in Game 1, nursing an injured right leg muscle, which he aggravated running out an infield single in his first at bat in Game 2. Stengel was obviously limping when he was advanced to second base on another single, and McGraw sent in a pinch runner. He did not use Stengel again in the Series, which the Giants won, four games to zero, with one tie. After the Series, Stengel and other major leaguers went on a barnstorming tour of Japan and the Far East.[51]

The year 1923 started much the same as the year before, with Stengel detailed to the "B" squad as player and coach in spring training, making the team as a reserve, and then inserted as center fielder when righties pitched. Similar also were Stengel's hot batting streaks, helping the Giants as they contended for their third straight pennant. Stengel was ejected several times for brawling or arguing with the umpire, and the league suspended him for ten games in one incident. McGraw continued to use him as a means of exerting some control over the younger players. During that summer, Stengel fell in love with Edna Lawson, a Californian who was running part of her father's building contracting business;[52] they were married the following year.[1] Near the end of the season, he sustained a mild foot injury, causing McGraw to rest him for a week, but he played the final two games of the regular season to finish at .339 as the Giants and Yankees each won their leagues.[53]

Until 1923, the Yankees had been tenants of the Giants at the Polo Grounds, but had opened Yankee Stadium that year, and this was the site for Game 1 of the 1923 World Series on October 10. Casey Stengel's at bat in the ninth inning with the score tied 4–4 was "the stuff of legend", as Appel put it in his history of the Yankees.[54] Before the largest crowd he had ever played before, Stengel lined a changeup from Joe Bush for a hit that went between the outfielders deep to left center. Hobbled by his injury and even more as a sponge inside his shoe flew out as he rounded second base, Stengel slowly circled the bases, and evaded the tag from catcher Wally Schang for an inside-the-park home run, providing the winning margin. Thus, the first World Series home run in old Yankee Stadium's history did not go to Babe Ruth, "that honor, with great irony, would fall to the aging reserve outfielder Casey Stengel".[54]

After the Yankees won Game 2 at the Polo Grounds, the Series returned to Yankee Stadium for Game 3. Stengel won it, 1–0, on a home run into the right field bleachers. As the Yankee fans booed Stengel, he thumbed his nose at the crowd and blew a kiss toward the Yankee players, outraging the team's principal owner, Jacob Ruppert, who demanded that Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis fine or suspend Stengel. Judge Landis declined, saying "a man who wins two games with home runs may feel a little playful, especially if he's a Stengel".[55] The Yankees won the next three games to take the Series; Stengel batted .417 in the six games, completing his World Series career as a player with a .393 batting average.[56]

It's lucky I didn't hit three home runs in three games, or McGraw would have traded me to the Three-I League.

On November 13, 1923, twenty-nine days after the World Series ended, Stengel was traded to the perennial second-division-dwelling Boston Braves with Dave Bancroft and Bill Cunningham for Joe Oeschger and Billy Southworth. Stengel had enjoyed his time in New York and was initially unhappy at the trade, especially since he had become close to McGraw. He soon cooled down, and later praised McGraw as "the greatest manager I ever played for".[56] Despite nagging pains in his legs, Stengel played in 134 games during the 1924 season, the most since his days with the Dodgers, and hit .280 with a team-leading 13 stolen bases, but the Braves finished last. After the season, Stengel joined a baseball tour of Europe organized by McGraw and Charles Comiskey, with Edna Stengel accompanying the team. Casey Stengel met King George V and the Duke of York, later to become King George VI; Edna sipped tea with Queen Mary, an experience that strained her nerves. That winter, the Stengels moved into a house built by Edna's father in Glendale, California, where they would live the rest of their lives.[57] The marriage produced no children.[58]

Early managerial career (1925–1948)

[edit]Minor leagues (1925–1931)

[edit]Never let a losing pitcher drive the bus—especially a left-hander. A guy who has just blown a tough one shouldn't be allowed behind the wheel.

Stengel started 1925 on the active roster of the Braves, but was used as a pinch hitter and started only once, in right field against the Pirates on May 14, a game in which he got his only MLB hit of 1925, the final one of his major league career, a single. His average sank to .077. Braves owner Emil Fuchs purchased the Worcester Panthers of the Eastern League, and hired Stengel as player-manager and team president.[60] Appel noted that in joining the Panthers, Stengel was "starting out on a managing career that would eventually take him to Cooperstown".[59] With fans enjoying Stengel's on-field antics and his World Series heroics still recent, he was the Eastern League's biggest attendance draw. Between run-ins with the umpires, Stengel hit .302 in 100 games as the Panthers finished third.[1][59]

The Panthers were not a box office success, and Fuchs planned to move the team to Providence, Rhode Island for the 1926 season, with Stengel to remain in his roles. McGraw, with whom Stengel had remained close, wanted him to take over as manager of the Giants' top affiliate, the Toledo Mud Hens of the American Association, at an increase in salary. Stengel was still under contract to the Braves, and Mud Hens president Joseph O'Brien was unwilling to send them money or players in order to get him. When Stengel asked Fuchs what to do if a higher-level club wanted to draft him, Fuchs half-heartedly suggested releasing himself as a player, which would automatically terminate his Braves contract. Stengel took up Fuchs on his suggestion, releasing himself as a player, then firing himself as manager and resigning as president, clearing the way for him to move to the Mud Hens. Fuchs was outraged, and went to Judge Landis, who advised him to let the matter go.[61][62]

People talk about all the money I've made. But they never talk about all the money I've lost.

Stengel's six years in Toledo would be as long as he would spend anywhere as manager, except his time with the Yankees of the 1950s.[64] McGraw sent talented players down to Toledo, and the Mud Hens threatened for the pennant in Stengel's first year before falling back to third. In 1927, the team won its first pennant and defeated the Buffalo Bisons, five games to one, in the Little World Series. Stengel missed part of the 1927 campaign, as he was suspended by the league for inciting the fans to attack the umpire after a close play during the first game of the Labor Day doubleheader.[65] Stengel continued as an occasional player as late as 1931 in addition to his managerial role, hitting a game-winning home run (the last of his professional career) in 1927 for the Mud Hens.[66] Since minor league clubs suffer large turnovers in their rosters, the team's success did not carry over to 1928, when it finished sixth, and then eighth in the eight-team league in 1929. The team recovered for third in 1930, but by then both Stengel and the team (in which he had invested) were having financial problems due to the start of the Great Depression. The team finished last again in 1931, and, after Landis was convinced no money had been skimmed off to benefit Stengel and other insiders, the team went into receivership, and Stengel was fired.[66]

Brooklyn and Boston (1932–1943)

[edit]

Stengel had approached the new manager of the Dodgers, Max Carey, an old teammate from his time with the Pirates, seeking a job, and was hired as first base coach. Stengel thus ended an exile of seven years from the major leagues: Appel suggested that Stengel's reputation as a clown inhibited owners from hiring him although he was known as knowledgeable and able to manage the press. Sportswriter Dan Daniel described Stengel's hiring as "the return of an ancient Flatbush landmark", which might satisfy old Dodger fans upset at Robinson's dismissal at the end of 1931.[67] Brooklyn finished third and then sixth with Stengel in the first base coaching box. Among the players was catcher Al Lopez; the two became close friends and would be managing rivals in the 1950s American League.[68]

The first thing I want to say is that the Dodgers are still in the National League. Tell that to Bill Terry.

During the winter following the 1933 season, the manager of the world champion Giants, Bill Terry was interviewed by the press about the other teams in the National League. When asked about the Dodgers, Terry responded, "Brooklyn? Gee, I haven't heard a peep out of there. Is Brooklyn still in the league?"[70] This angered Brooklyn's management, and they expected Carey to make a full-throated response. When he remained silent, he was fired. One sportswriter regarded the hiring of Stengel as too logical a thing to happen in Brooklyn, but on February 24, 1934, Stengel faced the press for the first time as the manager of a major league team.[69] McGraw, Stengel's mentor, was too ill to issue a statement on seeing him become a major league manager; he died the following day.[71]

Stengel, hired only days before spring training, had a limited opportunity to shape his new ballclub. The Dodgers quickly settled into sixth place, where they would end the season. Stengel, in later years, enjoyed discussing one 1934 game in Philadelphia's Baker Bowl: with Dodger pitcher Boom-Boom Beck ineffective, Stengel went out to the mound to take out the angry pitcher, who, instead of giving Stengel the baseball, threw it into right field, where it hit the metal wall with a loud noise. The right fielder, Hack Wilson, lost in thought, heard the boom, assumed the ball had been hit by a batter, and ran to retrieve it and throw it to the infield, to be met by general laughter.[72] Stengel got the last laughs on the Giants as well. The Giants, six games ahead of the Cardinals on Labor Day, squandered that lead, and with two games remaining in the season, were tied with St. Louis. The final two games were against Brooklyn at the Polo Grounds, games played in front of raucous crowds, who well remembered Terry's comments. Brooklyn won both games, while the Cardinals won their two games against the Cincinnati Reds, and won the pennant. Richard Bak, in his biography of Stengel, noted that the victories over the Terry-led Giants represented personal vindication for the Dodger manager.[73]

The Dodgers finished fifth in 1935 and seventh in 1936. Dodger management felt Stengel had not done enough with the talent he had been given, and he was fired during the 1936 World Series between the Yankees and Giants.[74] Stengel was paid for one year left on his contract, and he was not involved in baseball during the 1937 season. Stengel had invested in oil properties, as advised by one of his players, Randy Moore, a Texan; the investment helped make the Stengels well-to-do, and they put the profits in California real estate. Stengel considered going in the oil business full-time, but Braves president Bob Quinn offered him the Boston managerial job in late 1937, and he accepted.[75]

Stengel was both manager and an investor in the Braves. In his six years there, 1938 to 1943, his team never finished in the top half of the league standings, and the Boston club finished seventh four straight years between 1939 and 1942, saved from last place by the fact that the Phillies were even worse. The entry of the United States in World War II meant that many top players went into the service, but for the Braves, the changeover made little difference in the standings. Among the young players to join the Braves was pitcher Warren Spahn, who was sent down to the minor leagues by the manager for having "no heart".[76] Spahn, who would go on to a Hall of Fame career, much of it with the Braves, would play again for Stengel on the woeful New York Mets in 1965, and joke that he was the only person to play for Stengel both before and after he was a genius.[1][76]

A few days before the opening of the 1943 season, Stengel was hit by a vehicle while crossing Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, and he severely fractured a leg. He missed the first two months of the season, receiving many well-wishers, and reading get-well cards jokingly misaddressed to the hospital's psychiatric ward. For the rest of his life, Stengel walked with a limp. At the end of the season, Braves management, tired of minimal progress, fired Stengel, and he received no immediate job offers.[77] Stengel testified about this part of his career before a Senate subcommittee fifteen years later, "I became a major league manager in several cities and was discharged. We call it discharged because there is no question I had to leave".[78]

Return to the minors (1944–1948)

[edit]

Stengel thought the 1943 season would be his last in baseball; Edna urged him to look after the family business interests full-time, and Casey, who had always been an athlete, was reluctant to show himself at a baseball stadium with the imperfectly healed injury. But early in the 1944 season, the minor-league Milwaukee Brewers had a managing vacancy to fill, as the Chicago Cubs had hired away the Brewer manager, Charlie Grimm, who had played with Stengel on the 1919 Pirates. Grimm told the Cubs he was obliged to see the Brewers had a competent replacement, and urged the Brewers to hire Stengel. The team owner, Bill Veeck, stationed as a Marine on Guadalcanal, thought ill of Stengel as a manager, and was very reluctant in his consent when reached by cable. Stengel was adept at fostering good relations with reporters, and the very talented team continued to win; by the end of May, Veeck had withdrawn his objections. The team won the American Association pennant, but lost in the playoffs to Louisville. Veeck, having returned to the United States, offered to rehire Stengel for 1945, but Stengel preferred another offer he received.[79] This was from George Weiss of the New York Yankees, to manage the team Stengel had begun with, the Kansas City Blues, by then a Yankee farm club. Kansas City had finished last in the American Association as Milwaukee won the pennant, making it something of a comedown for Stengel, who hoped to return to the major leagues. Nevertheless, it was in his old home town, allowing him to see friends and relations, and he took the job. The Blues finished seventh in the eight-team league in 1945.[80]

Every manager wants to throw himself off a bridge sooner or later, and it's very nice for an old man to know he doesn't have to walk fifty miles to find one.

Although there was no major league managing vacancy Stengel could aspire to, the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League had fired their manager, and approached Stengel. The baseball played in the PCL was close to major league level, and the league featured many aging big leaguers finishing their careers. Also attractive to Stengel was that the league had three teams in Southern California, allowing him to spend more time at his home in Glendale. To that time, the club had won only one pennant, and was something of a weak sister to its crossbay rivals, the San Francisco Seals, but owner Brick Laws believed Stengel could mold the players into a winning team.[82]

The Oaks finished second in the league behind the Seals in 1946, winning the first round of the playoffs against Los Angeles before losing to San Francisco in the finals. They finished fourth in 1947, beating San Francisco in the first round before losing to Los Angeles. Stengel managed the Oaks for a third year in 1948, with the roster heavy with former major leaguers. Among the younger players on the team was 20-year-old shortstop Billy Martin. Stengel was impressed by Martin's fielding, baseball acuity, and, when there were brawls on the field, fighting ability. The Oaks clinched the pennant on September 26, and defeated Los Angeles and the Seattle Rainiers to win the Governors' Cup. The Sporting News named Stengel the Minor League Manager of the Year.[83]

Glory days: Yankee dynasty (1949–1960)

[edit]Hiring and 1949 season

[edit]"So what if he doesn't talk to me? I'll get by and so will he. DiMaggio doesn't get paid to talk to me and I don't either.

Stengel had been talked about as a possible Yankee manager in the early 1940s, but longtime team boss Ed Barrow (who retired in 1945) refused to consider it.[85] Yankee manager Joe McCarthy retired during the 1946 season, and after the interim appointment of catcher Bill Dickey as player-manager, Bucky Harris was given the job in 1947.[86] Stengel's name was mentioned for the job before Harris got it; he was backed by Weiss, but Larry MacPhail, then in charge of the franchise, was opposed.[87] Harris and the Yankees won the World Series that year, but finished third in 1948, though they were not eliminated until the penultimate day. Harris was fired, allegedly because he would not give Weiss his home telephone number.[86] MacPhail could no longer block Stengel's hiring, as he had sold his interest in the Yankees after the 1947 season. Weiss, who became general manager after MacPhail's departure, urged his partners in the Yankees to allow the appointment of Stengel, who aided his own cause by winning the championship with Oakland during the time the Yankee job stood open. Del Webb, who owned part of the Yankees, had initial concerns but went along.[88] Yankee scouts on the West Coast recommended Stengel, and Webb's support helped bring around co-owner Dan Topping.[89]

Stengel was introduced as Yankee manager on October 12, 1948, the 25th anniversary of his second World Series home run to beat the Yankees. Joe DiMaggio attended the press conference as a sign of team support. Stengel faced obstacles to being accepted—Harris had been popular with the press and public, and the businesslike Yankee corporate culture and successful tradition were thought to be ill matched with a manager who had the reputation of a clown and who had never had a major league team finish in the top half of the standings. Stengel's MLB involvement had been in the National League, and there were several American League parks in which he had neither managed nor played.[89][90][91]

Stengel tried to keep a low profile during the 1949 Yankee spring training at St. Petersburg, Florida,[1] but there was considerable media attention as Stengel shuttled rookies from one position on the field to another, and endlessly shuffled his lineup. He had the advantage of diminished expectations, as DiMaggio, the Yankee superstar, was injured with a bone spur in his heel, and few picked New York to win the pennant. There were other injuries once the season began, and Stengel, who had initially planned a conservative, stable lineup in his first American League season, was forced to improvise.[92] Although platooning, playing right-handed batters against left-handed pitchers and the reverse, against whom they are on average more able to hit, had been known for some years, Stengel popularized it, and his use gave the practice its name, coined by a sportswriter and borrowed from football. For example, in the early part of the 1949 season, Stengel might play Bobby Brown at third base and Cliff Mapes and Gene Woodling in the outfield against right-handers. Against left-handers, Stengel might play Billy Johnson at third with Johnny Lindell and Hank Bauer in the outfield.[93]

After the team blew leads and lost both ends of a doubleheader in Philadelphia on May 15, Stengel called a team meeting in which he criticized the players responsible for the two losses, but also predicted greatness for them, and told the team it was going to win. The team then won 13 of its next 14 games. Yankee sportscaster Curt Gowdy, who was present, later stated, "that speech in Philadelphia was the turning point of the season".[94]

DiMaggio returned from injury on June 28 after missing 65 games. He hit four home runs in three games to help sweep Boston and extend the Yankees' league lead. Despite DiMaggio's return, the lineup remained plagued with injuries. After consulting with Stengel, Weiss obtained Johnny Mize from the Giants, but he was soon sidelined with a separated shoulder. Twelve games behind on the Fourth of July, the Red Sox steadily gained ground on the Yankees, and tied them by sweeping a two-game set at Fenway September 24 and 25, the first time the Yankees had not been in sole possession of first place since the third game of the season. The Red Sox took the lead the following day with a comeback win in a makeup game, as Stengel lost his temper at the umpire for the first time in Yankee uniform; although he was not ejected, he was fined by the league.[95]

The season came down to a two-game set with the Red Sox at Yankee Stadium, with the home team one game behind and needing to win both. Stengel, during the 1949 season, had shown himself more apt than his peers to bring in a relief pitcher, and when during the first game, starter Allie Reynolds gave up the first two runs in the third inning, the manager brought in Joe Page. Though Page walked in two more runs, he shut out the Red Sox the rest of the way as the Yankees came back to win, 5–4. This set up a winner-take-all game for the league title. The Yankees took a 5–0 lead before Boston scored three in the ninth, but Vic Raschi was able to prevent further damage, giving the Yankees the pennant, Stengel's first as a major league manager.[96]

In the 1949 World Series, Stengel's first as a participant since 1923, the Yankees faced the Brooklyn Dodgers, who were assembling the team that would challenge the Yankees through much of his time in New York. The teams split the first two games, at Yankee Stadium. Before Game 3 at Ebbets Field, Stengel was called upon to introduce his surviving teammates from the 1916 pennant-winning Brooklyn club, which he did emotionally. The Yankees won Game 3, and during Game 4, a Yankee victory, Stengel left the dugout to shout to catcher Yogi Berra to throw the ball to second base, which Berra did to catch Pee Wee Reese trying to take an extra base. For this breach of baseball's rules, Stengel was reprimanded after the game by Commissioner Happy Chandler. The Yankees won Game 5 as well to take the Series, and during the celebration after the game, Del Webb said of Stengel to the press, "I knew he would win, whether we got some more players for him or not".[97]

Repeating success (1950–1953)

[edit]

During the 1949 season, Stengel had been more subdued than he usually was, but being the manager of the defending world champions and the Major League Manager of the Year relieved his inhibitions, and he was thereafter his talkative self. He also was more forceful in running the team, not always to the liking of veteran players such as DiMaggio and Phil Rizzuto. As part of his incessant shuffling of the lineup, Stengel had DiMaggio play first base, a position to which he was unaccustomed and refused to play after the first game. Stengel considered DiMaggio's decline in play as he neared the end of his stellar career more important than his resentment. In August, with the slugger in the middle of a batting slump, Stengel benched him, stating he needed a rest. DiMaggio returned after six games, and hit .370 for the rest of the season, winning the slugging percentage title. Other young players on the 1950 team were Billy Martin and Whitey Ford. The ascendence of these rookies meant more of the Yankees accepted Stengel's techniques, and diminished the number of those from the McCarthy era who resented their new manager. The Detroit Tigers were the Yankees' main competition, leading for much of the summer, but the Yankees passed them in the middle of September to win the pennant by three games. In the 1950 World Series, the Yankees played the Phillies, another of Stengel's old teams. The Yankees won in four games.[1][98]

He's just a green pea out there. But he'll be back soon, and you'll see something.

Before spring training in 1950, the Yankees had pioneered the idea of an instructional school for rookies and other young players. This was the brainchild of Stengel and Weiss. Complaints from other teams that the Yankees were violating time limits on spring training and were using their money for competitive advantage led to modifications, but the concept survived and was eventually broadly adopted.[100] Among those invited to the 1951 early camp was 19-year-old Mickey Mantle, whose speed and talent awed Stengel, and who had spent the previous year in the minor leagues.[101] Stengel moved Mantle from shortstop to the outfield, reasoning that Rizzuto, the shortstop, was likely to play several more years. Both Mantle and the Yankees started the 1951 season slowly,[1] and on July 14, Mantle was sent to Kansas City to regain his confidence at the plate. He was soon recalled to the Yankees; although he hit only .267 for the season, this was four points better than DiMaggio, in his final season. Much of the burden of winning a third consecutive pennant fell on Berra, who put together an MVP season.[102] The White Sox and then the Indians led the league for much of the summer, but the Yankees, never far behind, put together a torrid final month of the season to win the pennant by five games.[1]

The Yankee opponent in the 1951 World Series was the Giants, with Game 1 played the day after they won the National League pennant in the Miracle of Coogan's Bluff. On an emotional high,[103] the Giants beat the Yankees in Game 1 at Yankee Stadium. Game 2 was a Yankee victory, but Mantle suffered a knee injury and was out for the Series,[104] the start of knee problems that would darken Mantle's career.[105] The Giants won Game 3, but DiMaggio stepped to the fore, with six hits in the following three games, including a home run to crown his career. The Yankees won Games 4 and 5,[104] and staked Raschi to a 4–1 lead in Game 6 before Stengel had Johnny Sain pitch in relief. When Sain loaded the bases with none out in the ninth, Stengel brought in Bob Kuzava, a left-hander, to pitch against the Giants, even though right-handers Monte Irvin and Bobby Thomson were due to bat. The Giants scored twice, but Kuzava hung on. The Yankees and Stengel had their third straight World Series championship.[106]

DiMaggio's retirement after the 1951 season gave Stengel greater control over the players, as the relationship between superstar and manager had sometimes been fraught. Stengel moved Mantle from right to center field in DiMaggio's place.[107] The Yankees were not the favorites to win the pennant again in 1952, with DiMaggio retired, Mantle still recovering from his injury and several Yankees in military service, deployed in the Korean War. Sportswriters favored the Indians. Younger players, some of whom Stengel had developed, came to the fore, with Martin the regular second baseman for the first time. Mantle proved slow to develop, but hit well towards the end of the season to finish at .311.[108] The Yankee season was also slow to get on track; the team had a record of 18–17 on May 30, but they improved thereafter. Stengel prepared nearly 100 different lineup cards for the 1952 season. The race was still tight in early September, and on September 5, Stengel lectured the team for excessive levity on the train after the Yankees lost two of three to Philadelphia. Embarrassed by the episode, which made its way into print, the Yankees responded by winning 15 of their next 19, clinching the pennant on September 27.[109]

The 1952 World Series was against the Brooklyn Dodgers, who by then had their stars of the 1950s such as Jackie Robinson, Gil Hodges and Duke Snider, with the team later nicknamed "The Boys of Summer".[110] The teams split the first four games. With his pitching staff tired, Stengel gave the start to late-season acquisition Ewell Blackwell, who surrendered four runs in five innings, and the Yankees lost the game in 11 innings to the Dodgers behind Carl Erskine's complete game.[111] Needing to win two in a row at Ebbets Field, Stengel pitched Raschi in Game 6, who won it with a save from Reynolds. With no tomorrow in Game 7, Stengel sent four pitchers to the mound. Mantle hit a home run to break a 2–2 tie, Martin preserved the lead by making a difficult catch off a Robinson popup, and Kuzava again secured the final outs for a Series victory, as the Yankees won 4–2 for their fourth straight World Series victory, matching the record set in 1936–1939, also by the Yankees.[110]

The sportswriters had picked other teams to win the pennant in Stengel's first four years as Yankee manager; in 1953 they picked the Yankees, and this time they were proven correct. An 18-game winning streak in June placed them well in front, and they coasted to their fifth consecutive league championship, the first time a team had won five straight pennants.[108] The Yankees played the Dodgers again in the World Series, which was less dramatic than the previous year's, as the Yankees won in six games, with Mantle, Martin, Berra and Gil McDougald—players developed under Stengel—taking the fore. The Yankees and Stengel won the World Series for the fifth consecutive year, the only team to accomplish that feat. Stengel, having taken the managerial record for consecutive pennants from McGraw (1921–1924) and McCarthy (1936–1939) and for consecutive titles from the latter, would say, "You know, John McGraw was a great man in New York and he won a lot of pennants. But Stengel is in town now, and he's won a lot of pennants too".[112]

Middle years (1954–1958)

[edit]If the Yankees don't win the pennant, the owners should discharge me.

The Yankees started the defense of their title in 1954 with an opening day loss to the Washington Senators in the presence of President Dwight D. Eisenhower.[113] Even though the Yankees won 103 games, the most regular season victories they would have under Stengel, they lost by eight games to the Indians, managed by Stengel's old friend Al Lopez. In spite of the defeat, Stengel was given a new two-year contract at $75,000 per year.[114][115]

By the mid-1950s, Stengel was becoming a national figure,[116] familiar from television broadcasts of the Yankees on NBC's Game of the Week, and from managing in most World Series and All-Star Games during his tenure.[117] National magazines such as Look and Sports Illustrated did feature stories about Stengel, and his turn of phrase became known as "Stengelese". The magazines not only told stories about the manager's one-liners and jokes, but recounted the pranks from his playing days, such as the grapefruit dropped from the plane and the sparrow under the cap.[118] According to Richard Bak in his biography of Stengel, "people across the country grew enamored of the grandfatherly fellow whose funny looks and fractured speech were so at odds with the Yankees' bloodless corporate image".[119]

The Yankees won the pennant again in 1955, breaking open a close pennant race in September to take the American League. They played the Dodgers again in the World Series, which the Dodgers won in seven games. The Dodgers won Game 7, 2–0, behind the pitching of Johnny Podres and Stengel, after losing his first World Series as a manager, blamed himself for not instructing his hitters to bat more aggressively against Podres. Billy Martin stated, "It's a shame for a great manager like that to have to lose".[120]

There was not much of a pennant race in the American League in 1956, with the Yankees leading from the second week of the season onwards. With little suspense as to the team's standing, much attention turned to Mantle's batting, as he made a serious run at Babe Ruth's record at the time of 60 home runs in a season, finishing with 52, and won the Triple Crown. On August 25, Old-Timers' Day, Stengel and Weiss met with the little-used Rizzuto, the last of the "McCarthy Yankees" and released him from the team so they could acquire Enos Slaughter. Never a Stengel fan, the process left Rizzuto bitter.[121][122]

The World Series opponent that year was again the Dodgers, who won the first two games at Ebbets Field. Stengel lectured the team before Game 3 at Yankee Stadium and the team responded with a victory then and in Game 4. For Game 5, Stengel pitched Don Larsen, who had been knocked out of Game 2, and who responded with a perfect game, the only one in major league postseason history. The Dodgers won Game 6 as the Series returned to Ebbets Field. Many expected Whitey Ford to start Game 7, but Stengel chose Johnny Kucks, an 18-game winner that season who had been used twice in relief in the Series. Kucks threw a three-hit shutout as the Yankees won the championship, 9–0, Stengel's sixth as their manager.[123][124]

New York got off to a slow start in the 1957 season, and by early June was six games out. By then, the team was making headlines off the field. Some of the Yankees were known for partying late into the night, something Stengel turned a blind eye to as long as the team performed well. The May 16 brawl at the Copacabana nightclub in New York involved Martin, Berra, Mantle, Ford, Hank Bauer and other Yankees, resulted in the arrest of Bauer (the charge of assault was later dropped) and exhausted Yankee management's patience with Martin. Stengel was close to Martin, who took great pride in being a Yankee, and Topping and Weiss did not involve the manager in the trade talks that ensued. On June 15, Martin was traded to the Kansas City Athletics. Martin wrote in his autobiography that Stengel could not look him in the eye as the manager told him of the trade. The two, once close friends, rarely spoke in the years to come.[125]

The Yankees recovered from their slow start, winning the American League pennant by eight games. They faced the Milwaukee Braves in the 1957 World Series.[1] The Braves (Stengel had managed them when they played in Boston) defeated the Yankees in seven games, with Lew Burdette, who had been a Yankee until traded in 1950, beating New York three times. Stengel stated in an interview, "We're going to have Burditis on our minds next year".[126]

What was seen as a failure to keep discipline on the team hurt Stengel's standing with the Yankee owners, Topping, Weiss and Webb, as did the defeat in the 1957 Series. Stengel was by then aged 67 and had several times fallen asleep in the dugout, and players complained that he was growing more irritable with the years. Former Yankee catcher Ralph Houk, who had been successful as a minor league manager and was Stengel's first base coach, was seen by ownership as the next manager of the Yankees. Stengel's contract, his fifth two-year deal, was up after the 1958 season. As ownership debated whether to renew it, the Yankees led by as many as 17 games,[127] and won the pennant by 10.[1] The Braves were the opponent in the 1958 World Series. The Braves won three of the first four games, but the Yankees, backed by the pitching of Bob Turley (who got two wins and a save in the final three games) stormed back to win the Series. Firing Stengel under such circumstances was not possible, and ownership gave him another two-year contract, to expire after the 1960 season.[127]

Final years and firing (1959–1960)

[edit]The Yankees finished 79–75 in 1959, in third place, their worst record since 1925, as the White Sox, managed by Lopez, won the pennant. There was considerable criticism of Stengel, who was viewed as too old and out of touch with the players.[1][128]

After the 1959 season, Weiss made a trade with Kansas City to bring Roger Maris to the Yankees. Stengel was delighted with the acquisition and batted Maris third in the lineup, just in front of Mantle, and the new Yankee responded with an MVP season in 1960.[129] Stengel had health issues during the season, spending ten days in the hospital in late May and early June, with the illness variously reported as a bladder infection, a virus or influenza.[130] The Yankees were challenged by the Baltimore Orioles for most of the year but won the pennant by eight games, Stengel's tenth as manager, tying the major league record held by McGraw.[131][132]

The Yankees played the Pittsburgh Pirates, again a team Stengel had played for, in the 1960 World Series. Stengel picked Art Ditmar, who had won the most games, 15, for the Yankees, as the Game 1 starter rather than the established star, Whitey Ford. The Pirates knocked Ditmar out of the box in the first inning, and won Game 1.[131][132] Ditmar was also knocked out of Game 5; Ford won Games 3 and 6 of the seven-game series with shutouts, but could not pitch Game 7, as he might have if Stengel had used him in Games 1 and 5. The Pirates defeated the Yankees in Game 7, 10–9, on a ninth-inning home run by Bill Mazeroski.[133][134]

I'll never make the mistake of being seventy again.

Shortly after the Yankees returned to New York, Stengel was informed by the team owners that he would not be given a new contract. His request, that the termination be announced at a press conference, was granted and on October 18, 1960, Topping and Stengel appeared before the microphones. After Topping evaded questions from the press about whether Stengel had been fired, Stengel took the microphone, and when asked if he had been fired, stated, "Quit, fired, whatever you please, I don't care". Topping stated that Stengel was being terminated because of his age, 70, and alleged that this would have happened even had the Yankees won the World Series.[136]

The Amazins': Casey and the Mets (1962–1965)

[edit]Hiring and 1962 season

[edit]Two days after dismissing Stengel, the Yankees announced the hiring of Houk as his replacement—part of the reason for Stengel's firing was so that New York would not lose Houk to another team. Stengel returned to Glendale, and spent the 1961 season out of baseball for the first time since 1937. He turned down several job offers to manage, from the Tigers, San Francisco Giants and the expansion Los Angeles Angels.[137] He spent the summer of 1961 as vice president of the Glendale Valley National Bank, which was owned by members of Edna Stengel's family.[1]

As part of baseball's expansion in the early 1960s, a franchise was awarded to New York, to play in the National League beginning in 1962, and to be known as the New York Mets. It was hoped that the new team would be supported by the many former Giant and Dodger fans left without a team when the franchises moved to California after the 1957 season. There were rumors through the 1961 season that Stengel would be the manager, but he initially showed no interest in managing a team that, given the rules for the expansion draft, was unlikely to be competitive. George Weiss had been forced out as Yankee general manager and hired by the Mets. He wanted Stengel as manager, and after talks with the Mets principal owners, Joan Whitney Payson and M. Donald Grant, Stengel was introduced as Mets manager at a press conference on October 2, 1961.[138] Leonard Koppett of The New York Times suggested that Stengel took the job to give something back to the game that had been his life for half a century.[139]

Look at that guy. He can't hit, he can't run, and he can't throw. Of course, that's why they gave him to us.

Weiss was convinced his scouting staff would make the Mets a respectable team in five to six years, but in the interim New York would most likely do poorly. He hoped to overcome the challenge of attracting supporters to a losing team in the "City of Winners" by drafting well-known players who would draw fans to the Polo Grounds, where the Mets would initially play. Thus, the Mets selected a number of over-the-hill National Leaguers, some of whom had played for the Dodgers or Giants, including Gil Hodges, Roger Craig, Don Zimmer and Frank Thomas. Selected before them all was journeyman catcher Hobie Landrith; as Stengel explained, "You have to have a catcher or you'll have a lot of passed balls".[141]

The return of Casey Stengel to spring training received considerable publicity, and when the Mets played the Yankees in an exhibition game, Stengel played his best pitchers while the Yankees treated it as a meaningless game, and the Mets won, 4–3. The team won nearly as many games as it lost in spring training, but Stengel warned, "I ain't fooled. They play different when the other side is trying too".[142] The Mets lost their first nine games of the regular season; in the meantime the Pirates were 10–0, meaning the Mets were already 91⁄2 games out of first place. Some light appeared in May, when the Mets won 11 of 18 games to reach eighth place in the ten-team league. They then lost 17 in a row, returning to last place, where they would spend the remainder of the season.[143]

According to sportswriter Joseph Durso,

on days when [Stengel's] amazing Mets were, for some reason, amazing, he simply sat back and let the writers swarm over the heroes of the diamond. On days when the Mets were less than amazing—and there were many more days like that—he stepped into the vacuum and diverted the writers' attention, and typewriters, to his own flamboyance ... the perfect link with the public was formed, and it grew stronger as the team grew zanier.[144]

The Mets appealed to the younger generation of fans and became an alternative to the stuffy Yankees. As the losing continued, a particular fan favorite was "Marvelous" Marv Throneberry, who was a "lightning-rod for disaster" in the 1962 season, striking out to kill rallies, or dropping pop flies and routine throws to first base.[145] During one game, Throneberry hit a massive shot to right, winding up on third base, only to be called out for missing first. Stengel came from the dugout to argue, only to be told that Throneberry had missed second base as well.[146]

Can't anyone play this here game?

Stengel tried incessantly to promote the Mets, talking to reporters or anyone else who would listen. He often used the word "amazin'" (as he put it) and soon this became the "Amazin' Mets", a nickname that stuck. Stengel urged the fans, "Come out and see my amazin' Mets. I been in this game a hundred years but I see new ways to lose I never knew existed before".[148] Stengel was successful in selling the team to some extent, as the Mets drew 900,000 fans, half again as many as the Giants had prior to their departure, though the games against the Giants and Dodgers accounted for half of the total. The team was less successful on the field, finishing with a record of 40–120, the most losses of any 20th century major league team.[149] They finished 601⁄2 games behind the pennant-winning Giants, and 18 games behind ninth-place Chicago.[150]

Later seasons and retirement (1963–1965)

[edit]

The 1963 season unfolded for the Mets much like the previous year's, though they lost only eight games to begin the season, rather than nine, but they still finished 51–111, in last place. One highlight, though it did not count in the standings, was the Mayor's Trophy Game on June 20 at Yankee Stadium. Stengel played to win; the Yankees under Houk possibly less so, and the Mets beat the Yankees, 6–2.[151]

In 1964, the Mets moved into the new Shea Stadium; Stengel commented that "the park is lovelier than my team".[152] The Mets finished 53–109, again in last place. By this time, the fans were starting to be impatient with the losing, and a number of people, including sportscaster Howard Cosell and former Dodger Jackie Robinson, criticized Stengel as ineffective and prone to fall asleep on the bench. Stengel was given a contract for 1965, though Creamer suggested that Weiss, Grant and Payson would have preferred that the 74-year-old Stengel retire.[153]

And we have this fine young catcher named Goossen, who is only twenty years old, who in ten years, he has a chance to be thirty.

The early part of the 1965 season saw similar futility. On July 25, the Mets had a party at Toots Shor's for the invitees to the following day's Old-Timers' Game. Sometime during that evening, Stengel fell off a barstool and broke his hip. The circumstances of his fall are not known with certainty, as he did not realize he had been severely injured until the following day. Stengel spent his 75th birthday in the hospital. Recognizing that considerable rehabilitation would be required, he retired as manager of the Mets on August 30, replaced by Wes Westrum, one of his coaches. The Mets would again finish in last place.[155]

Later years and death

[edit]

The Mets retired Stengel's uniform number, 37, on September 2, 1965, after which he returned to his home in California. He was kept on the team payroll as a vice president, but for all intents and purposes he was out of baseball. His life settled into a routine of attending the World Series (especially when in California), the All-Star Game, Mets spring training, and the baseball writers' dinner in New York. The writers, who elect members of baseball's Hall of Fame, considered it unjust that Stengel should have to wait the usual five years after retirement for election, and waived that rule. On March 8, 1966, at a surprise ceremony at the Mets spring training site in St. Petersburg, Stengel was told of his election; he was inducted in July along with Ted Williams. Thereafter, he added the annual Hall of Fame induction ceremony to his schedule.[156] In 1969, the "Amazin' Mets" justified their nickname by unexpectedly winning the World Series over the favored Orioles. Stengel attended the Series, threw out the first ball for Game 3 at Shea, and visited the clubhouse after the Mets triumphed in Game 5 to win the Series.[157] The Mets presented him with a championship ring.[158]

Most people my age are dead at the present time.

Stengel also participated in Old-Timers' Day at a number of ballparks, including, regularly, Shea Stadium.[159] In 1970, the Yankees invited him to Old-Timers' Day, at which his number, 37, was to be retired. By this time, the Yankee ownership had changed, and the people responsible for his dismissal were no longer with the team. He accepted and attended, and Stengel became the fifth Yankee to have his number retired. He thereafter became a regular at the Yankees' Old-Timers' Day.[160]

By 1971, Edna Stengel was showing signs of Alzheimer's disease,[161] and in 1973, following a stroke, she was moved into a nursing home.[1] Casey Stengel continued to live in his Glendale home with the help of his housekeeper June Bowdin. Stengel himself showed signs of senility in his last years, and during the final year of his life, these increased.[162] In his last year, Stengel cut back on his travel schedule, and was too ill to attend the Yankees' Old-Timers Day game in August 1975, at which it was announced that Billy Martin would be the new team manager.[163] A diagnosis of cancer of the lymph glands had been made, and Stengel realized he was dying. In mid-September, he was admitted to Glendale Memorial Hospital, but the cancer was inoperable. He died there on September 29, 1975. Stengel was interred in the Forest Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Glendale.[164]

The tributes to Stengel upon his death were many. Maury Allen wrote, "He is gone and I am supposed to cry, but I laugh. Every time I saw the man, every time I heard his voice, every time his name was mentioned, the creases in my mouth would give way and a smile would come to my face".[165] Richie Ashburn, a member of the 1962 Mets, stated, "Don't shed any tears for Casey. He wouldn't want you to ... He was the happiest man I've ever seen".[165] Jim Murray of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "God is certainly getting an earful tonight".[166]

Edna Stengel died in 1978,[167] and was interred next to her husband. In addition to the marker at their graves in Forest Lawn Cemetery, there is a plaque nearby in tribute to Casey Stengel, which besides biographical information contains a bit of Stengelese: "There comes a time in every man's life, and I've had plenty of them".[166]

Managerial record

[edit]| Team | Year | Regular season | Postseason[168] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Games | Won | Lost | Win % | Finish | Won | Lost | Win % | Result | ||

| BKN | 1934 | 152 | 71 | 81 | .467 | 6th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| BKN | 1935 | 153 | 70 | 83 | .458 | 5th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| BKN | 1936 | 154 | 67 | 87 | .435 | 7th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| BKN total | 459 | 208 | 251 | .453 | 0 | 0 | – | |||

| BOB | 1938 | 152 | 77 | 75 | .507 | 5th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| BOB | 1939 | 151 | 63 | 88 | .417 | 7th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| BOB | 1940 | 152 | 65 | 87 | .428 | 7th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| BOB | 1941 | 154 | 62 | 92 | .403 | 7th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| BOB | 1942 | 148 | 59 | 89 | .399 | 7th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| BOB | 1943 | 107 | 47 | 60 | .439 | 6th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| BOB total | 864 | 373 | 491 | .432 | 0 | 0 | – | |||

| NYY | 1949 | 154 | 97 | 57 | .630 | 1st in AL | 4 | 1 | .800 | Won World Series (BKN) |

| NYY | 1950 | 154 | 98 | 56 | .636 | 1st in AL | 4 | 0 | 1.000 | Won World Series (PHI) |

| NYY | 1951 | 154 | 98 | 56 | .636 | 1st in AL | 4 | 2 | .667 | Won World Series (NYG) |

| NYY | 1952 | 154 | 95 | 59 | .617 | 1st in AL | 4 | 3 | .571 | Won World Series (BKN) |

| NYY | 1953 | 151 | 99 | 52 | .656 | 1st in AL | 4 | 2 | .667 | Won World Series (BKN) |

| NYY | 1954 | 154 | 103 | 51 | .669 | 2nd in AL | – | – | – | – |

| NYY | 1955 | 154 | 96 | 58 | .623 | 1st in AL | 3 | 4 | .429 | Lost World Series (BKN) |

| NYY | 1956 | 154 | 97 | 57 | .630 | 1st in AL | 4 | 3 | .571 | Won World Series (BKN) |

| NYY | 1957 | 154 | 98 | 56 | .636 | 1st in AL | 3 | 4 | .429 | Lost World Series (MIL) |

| NYY | 1958 | 154 | 92 | 62 | .597 | 1st in AL | 4 | 3 | .571 | Won World Series (MIL) |

| NYY | 1959 | 154 | 79 | 75 | .513 | 3rd in AL | – | – | – | – |

| NYY | 1960 | 154 | 97 | 57 | .630 | 1st in AL | 3 | 4 | .429 | Lost World Series (PIT) |

| NYY total | 1845 | 1149 | 696 | .623 | 37 | 26 | .587 | |||

| NYM | 1962 | 160 | 40 | 120 | .250 | 10th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| NYM | 1963 | 162 | 51 | 111 | .315 | 10th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| NYM | 1964 | 162 | 53 | 109 | .327 | 10th in NL | – | – | – | – |

| NYM | 1965 | 95 | 31 | 64 | .326 | retired | – | – | – | – |

| NYM total | 579 | 175 | 404 | .302 | 0 | 0 | – | |||

| Total[168] | 3747 | 1905 | 1842 | .508 | 37 | 26 | .587 | |||

Awards and honors

[edit]You could look it up.

As part of professional baseball's centennial celebrations in 1969, Stengel was voted its "Greatest Living Manager".[170] He had his uniform number, 37, retired by both the Yankees and the Mets. He is the first man in MLB history to have had his number retired by more than one team based solely upon his managerial accomplishments, and was joined in that feat in 2011 by the late Sparky Anderson, who had called Stengel "the greatest man" in the history of baseball.[171][172] The Yankees dedicated a plaque in Yankee Stadium's Monument Park in Stengel's memory on July 30, 1976, reading: "Brightened baseball for over 50 years; with spirit of eternal youth; Yankee manager 1949–1960 winning 10 pennants and 7 world championships including a record 5 consecutive, 1949–1953".[167] He was inducted into the New York Mets Hall of Fame in 1981.[173]

Stengel is the only man to have worn the uniform (as player or manager) of all four Major League Baseball teams in New York City in the 20th century: the Dodgers, Giants, Yankees and Mets.[174] He is the only person to have played or managed for the home team in five New York City major league venues: Washington Park, Ebbets Field, the Polo Grounds, Shea Stadium and the original Yankee Stadium.[175] In 2009, in an awards segment on the MLB Network titled "The Prime 9", he was named "The Greatest Character of The Game", beating out Yogi Berra.[176]

Managerial techniques

[edit]Stengel re-invigorated platooning in baseball. Most of Stengel's playing days were after offensive platooning, choosing left-handed batters against a right-handed pitcher and the converse, was used successfully by the World Series champion 1914 Boston "Miracle" Braves. This set off widespread use of platooning: Stengel himself was several times during his playing career platooned against right-handers, but the practice fell into disuse around 1930. Stengel reintroduced it to the Yankees, and its prominent use amid the team's success caused it to be imitated by other teams.[177][178][179] Bill James deemed Stengel and Earl Weaver the most successful platoon managers.[180]

This strategic selection also applied to the pitchers, as Stengel leveraged his staff, starting his best pitchers against the best opponents. Although Stengel is best known for doing this with the Yankees, he also did it in his days managing Brooklyn and Boston, and to a very limited extent with the Mets.[181] Rather than have a regular pitching rotation to maximize the number of starts a pitcher will have, Stengel often rested pitchers longer to take advantage of situational advantages which he perceived. For example, Stengel started Eddie Lopat against Cleveland whenever possible, because he regularly beat them. Stengel's 1954 Yankees had the highest sabermetrics measurement of Leverage Points Average of any 20th century baseball team. Leveraging became unpopular after choices of starting pitchers based on it backfired on Lopez in the 1959 World Series and on Stengel in the following year's—he waited until Game 3 to start Whitey Ford because he felt Ford would be more effective at Yankee Stadium rather than at the small Forbes Field. Ford pitched two shutouts, including Game 6 at Forbes Field, but could not pitch in the Yankees' Game 7 loss. Stengel's philosophy took another blow in 1961 when Houk used Ford in a regular rotation and the pitcher went 25–4 and won the Cy Young Award—he had never won 20 games under Stengel. Today, teams prefer, for the most part, a regular rotation.[182]

James noted that Stengel was not only the most successful manager of the 1950s, he was the most dominant manager of any single decade in baseball history.[183] Stengel used his entire squad as Yankee manager, in contrast to other teams when he began his tenure, on which substitutes tended to get little playing time. Stengel's use of platooning meant more players saw more use, and he was generally more prone to put in a pinch hitter or replace his pitcher than other managers. Although only once in Stengel's time (1954) did the Yankees lead the league in number of pinch hitters, Stengel was known for using them in odd situations, once pinch-hitting for Moose Skowron in the first inning after a change of pitcher. Additionally, according to James, Stengel "rotated lineups with mad abandon, using perhaps 70 to 100 different lineups in a 154 game season".[184] Although Stengel was not the first Yankee manager to use a regular relief pitcher—Harris had seen success with Joe Page in 1947—his adoption of the concept did much to promote it.[185]

Stengel often rotated infielders between positions, with the Yankees having no real regular second baseman or shortstop between 1954 and 1958. Despite this, the Yankees had a strong defensive infield throughout. Stengel gave great attention to the double play, both defensively and in planning his lineup, and the Yankees responded by being first in the league in double plays as a defense six times in his twelve-year tenure, and the batters hit into the fewest double plays as a team eight times in that era.[186] Having had few players he could rely upon while managing Brooklyn and Boston, Stengel treated his Yankee roster with little sentimentality, trading players quickly when their performance seemed to decline, regardless of past accomplishments. Assured of quality replacements secured by the Yankee front office, the technique worked well, but was not a success with the Mets, where no quality replacements were available, and the technique caused confusion and apathy among the players.[187]

Appraisal

[edit]The secret of managing is to keep the five guys who hate you away from the guys who are undecided.

Marty Appel wrote of Stengel, "He was not a man for all seasons; he was a man for baseball seasons".[189] Stengel remains the only manager to lead his club to victory in five consecutive World Series.[190] How much credit he is due for that accomplishment is controversial, due to the talent on the Yankee teams he managed—Total Baseball deemed that the Yankees won only six games more than expected during the Stengel years, given the number of runs scored and allowed.[1] According to Bak, "the argument—even among some Yankees—was that the team was so good anybody could manage it to a title".[191] Rizzuto stated, "You or I could have managed and gone away for the summer and still won those pennants".[192] Appel noted, "There was no doubt, by taking on the Mets job, he hurt his reputation as a manager. Once again, it was clear that with good players he was a good manager, and with bad players, not. Still, his Yankee years had put him so high on the list of games won, championships won, etc., that he will always be included in conversations about the greatest managers".[193]

Bill Veeck said of Stengel in 1966, soon after the manager's retirement, "He was never necessarily the greatest of managers, but any time he had a ball club that had a chance to win, he'd win".[194] Stengel's American League rival, Al Lopez, once said of him "I swear I don't understand some of the things he does when he manages".[195] Though platooning survives, Stengel's intuitive approach to managing is no longer current in baseball, replaced by the use of statistics, and the advent of instant replay makes obsolete Stengel's tendency to charge from the dugout to confront an umpire over a disputed call.[196]

Stengel has been praised for his role in successfully launching the Mets. Appel deemed the Mets' beginnings unique, as later expansion teams have been given better players to begin with, "few expansion teams in any sport have tried the formula—a quotable, fan-popular man who would charm the press and deflect attention away from ineptness on the field".[158] Arthur Daley of The New York Times wrote, "he gave the Mets the momentum they needed when they needed it most. He was the booster that got them off the ground and on their journey. The smoke screen he generated to accompany the blast-off obscured the flaws and gave the Mets an acceptance and a following they could not have obtained without him".[197] James wrote, "Stengel became such a giant character that you really can't talk about him in the past. He became an enduring part of the game".[198] Commissioner William Eckert said of Stengel, "he's probably done more for baseball than anyone".[197]

A child of the Jim Crow era, and from a border state (Missouri) with southern characteristics, Stengel has sometimes been accused of being a racist, for example by Roy Campanella Jr., who stated that Stengel made racist remarks from the dugout during the World Series towards his father Roy Campanella, Jackie Robinson and other black stars of the Dodgers. Bak noted, though, that Stengel was a "vicious and inventive" bench jockey, hazing the other team with whatever might throw off their performance.[199] Stengel had poor relations with Robinson; each disliked the other and was a vocal critic.[200] One widely quoted Stengel comment was about catcher Elston Howard, who became the first black Yankee in 1955, eight years after Robinson had broken the color barrier, "they finally get me a nigger, I get the only one who can't run".[201] Howard, though, denied that Stengel had shouted racial epithets at the Dodgers, and said "I never felt any prejudice around Casey".[202] Al Jackson, a black pitcher with the Mets under Stengel, concurred, "He never treated me with anything but respect".[203] According to Bill Bishop in his account of Stengel, "Casey did use language that would certainly be considered offensive today, but was quite common vernacular in the fifties. He was effusive in his praise of black players like Satchel Paige, Larry Doby and Howard".[1] Conscious of changing times, Stengel was more careful in his choice of words while with the Mets.[204]