No-ball

In cricket, a no-ball[a] (in the Laws and regulations: "No ball") is a type of illegal delivery to a batter (the other type being a wide). It is also a type of extra, being the run awarded to the batting team as a consequence of the illegal delivery. For most cricket games, especially amateur, the definition of all forms of no-ball is from the MCC Laws of Cricket.[1]

Originally "no Ball" was called when a bowler overstepped the bowling crease, requiring them to try again to bowl a fair ball.

As the game developed, "No ball" has also been called for an unfair ball delivered round-arm, over-arm or thrown, eventually resulting in today's over-arm bowling being the only legal style.

Technical infringements, and practices considered unfair or dangerous, have been added for bowling, field placement, fielder and wicket-keeper actions. "No-ball" has become a passage of play.

The delivery of a no-ball results in one run – two under some regulations – to be added to the batting team's overall score, and an additional ball must be bowled. In addition, the number of ways in which the batter can be given out is reduced to three. In shorter competition cricket, a batter receives a free hit on the ball after any kind of no-ball, which means the batter can freely hit that one ball with no danger of being out in most ways.

No-balls due to overstepping the crease are common, especially in short form cricket, and fast bowlers tend to bowl them more often than spin bowlers.

It is also a no-ball when the bowler's back foot lands touching or wide of the return crease.

Any of the many no-ball cases is at least 'unfair' to the extent that the batting team is given a fair ball and a penalty run in compensation. Some no-balls are given under Law 41[2] 'Unfair Play' and hence have further repercussions: a fast short pitched delivery (a "bouncer") may be judged to be a no-ball by the umpire (Law 41.6), and any high full-pitched delivery (a "beamer", Law 41.7), or any deliberate front-foot fault (deliberate overstepping, Law 41.8), is inherently dangerous or unfair.

Any beamer is unfair and therefore a no-ball, but the umpire may judge that a particular beamer is not also dangerous, and does not warrant a warning or suspension.[3]

For deliberate beamers and deliberate overstepping, the bowler may be suspended from bowling immediately, and the incident reported. For other dangerous and unfair no-balls, or for throwing, repetition will have additional consequences for the bowler and team. The bowler may be suspended from bowling in the game, reported, and required to undertake remedial work on their bowling action.

Causes

[edit]A no-ball may be called for several reasons,[1][2][4][5] most commonly because the bowler breaks the first rule below (a front foot no-ball), and also frequently as a result of dangerous or unfair bowling.

Note that if a ball qualifies as both a no-ball and a wide, it is a no-ball.[1]

The umpire will call a no-ball in any of the following situations:

Illegal action by the bowler

[edit]Position of feet

[edit]"Overstepping"

- If the bowler bowls without some part of the front foot behind the popping crease (either grounded or in the air) when it lands. If the front foot of a bowler lands behind the crease and slides beyond, then it is not a no-ball. If the foot lands beyond the crease, it is a no-ball. It is legal for a spin bowler, for example, to land with their toe spikes grounded wholly in front of the crease but to have their heel in the air behind that line. The bowler must satisfy the umpire that some part of the foot lands initially behind the line,[1] and in big games this question is now subject to minute examination by television replay. Recent practice has been to allow the bowler the benefit of any residual doubt in this judgement. Note: the crease refers to the inside edge of the painted line, not the line itself.

Wide of the Crease

- If the bowler bowls with any part of the back foot wide of - i.e. on or outside the line of - the return crease when it lands. Any part of the back foot can legally be in the air outside of the crease, and it can be even be grounded after landing. It is legal for a spin bowler, for example, to land with their toe spikes grounded wholly within the return crease but to have their heel in the air wide of that line. The bowler must satisfy the umpire that no part of the foot lands initially on or outside the line, and again if it ever (rarely) arises in big games this question may now be subject to minute examination. In one example New Zealand slow bowler Glenn Phillips was shown on Umpire Review replay to have grounded almost his entire back foot wide of the return crease in the act of bowling a wicket-taking ball to Jos Buttler, but was adjudged to have grounded only the toe in the act of landing, and this wholly within the return crease, thus the ball was adjudged legal by the third umpire, and the batter given out. [6]

One side of the Wicket

- If the bowler bowls without some part of the front foot landing either grounded or in the air on the same side of the wicket as the back foot lands.

Method of delivery

[edit]- If the bowler throws, rather than bowls, the ball. (See bowling, bowling action and especially throwing for an explanation.)

- If the bowler breaks the non-striker's wicket during the act of delivery (unless attempting to run out the non-striker).

- If the bowler changes the arm with which they bowl without notifying the umpire.

- If the bowler changes the side of the wicket from which they bowl without notifying the umpire.

- If the bowler bowls underarm unless this style of delivery is agreed before the match.

- If the ball bounces more than once, or rolls along the ground, before reaching the popping crease at the striker's end.[1]

- If the ball bounces not wholly within the 10 foot width of a full pitch, or bounces wholly or partly on an artificial surface next to the pitch, or bounces not wholly on the artificial surface in use.

- If the ball comes to rest in front of the line of the striker's wicket.

- If the ball is so far from the pitch that the batter would be obliged to leave the pitch to play it

Unfair / dangerous bowling

[edit]- If the ball does not touch the ground in its flight between the wickets and reaches the batter on the full (this delivery is called a beamer) over waist height. 'Waist' means the top of the trousers when the batter is standing upright at the popping crease.[2]

- If the bowler bowls any fast short pitch ball (bouncer) that, taking into account its trajectory and the skill of the batter, is dangerous.[2]

- If the bowler bowls a ball that bounces and passes the batter above head height [1]

- If the bowler repeatedly bowls balls that bounce and pass the batter above head height, the bowling can also be judged unfair by the umpire under Law 41, even if not dangerous as above, and incurs the same sanctions.[2]

In professional cricket, the Laws of Cricket are often modified by a playing regulation that any ball over head height is a Wide ball, but a second fast ball above shoulder height in an over is a no-ball, e.g. in International T20 Cricket[7] and IPLT20.[8] But in International One-Day Cricket[9] and in Test Cricket,[10] two fast pitched short balls per over may pass over shoulder height before no-ball is called, and again any ball over head height is a Wide. Thus competition rules may both tone down the definition of 'dangerous and unfair' (a Wide is a lesser sanction than a no-ball, and cannot be applied if the batter hits, or is hit by, the delivery) and put definite limits on repetition, intended not only to protect the batter but also to maintain a fair contest between bat and ball, preventing such bowling being used to limit the batter's ability to score. There is presently some difference of opinion between the authorities that is evident in the differences between Law and regulation.

Illegal action by a fielder

[edit]- If the wicket keeper moves any part of their person in front of the line of the stumps before either a) the ball strikes the batter's person or bat; or b) the ball passes the line of the stumps.[4]

- If a fielder (not including bowler) has any part of their body grounded or in the air over the pitch.[5]

- If a fielder intercepts the ball before it has hit the striker or their bat or passed their wicket. The ball also becomes dead immediately.

- If there are more than two fielders that are on the leg side and behind the batter's crease.

- Under certain playing conditions, further restrictions apply to the placement of fielders. For example in One Day International cricket, there can be no more than five fielders a) on the on side; and b) outside the 30-yard circle. (The bowler is not a fielder when counting fielder placement).

Umpire making the call of no-ball

[edit]By default, it is the bowler's end umpire who calls and signals no-ball. When judgement of ball height is required (for beamers and short balls), their colleague (the striker's end umpire) will assist them with a signal.

In the event of a wicket, the umpire can signal a no-ball after the fall of that illegal wicket and call back the batter. Either umpire may call a bowler for throwing, although the striker's end umpire is naturally better-placed, and so has the primary responsibility.

The striker's end umpire calls no-ball for infringement by the wicket-keeper, and for position of the fielders, but the bowler's end umpire calls no-ball for fielder encroachment on the wicket.[11]

The bowler's end umpire initially signals a foot-fault no-ball by holding one arm out horizontally and calling "no-ball", which may give the batter some warning that the ball is an illegal delivery. Other reasons for a no-ball, e.g. illegal position of fielder, throwing the ball, or height of delivery, are initially judged by the striker's end umpire, who indicates their judgement to the bowler's end umpire.

When the ball is dead, the umpire will repeat the no-ball hand signal for the benefit of the scorers, and wait for their acknowledgement.

Effects

[edit]Dismissal

[edit]A batter may not be given out bowled, leg before wicket, caught, stumped or hit wicket off a no-ball. A batter may be given out run out, hit the ball twice or obstructing the field. Thus the call of no-ball protects the batter against losing their wicket in ways that are attributed to the bowler, but not in ways that are attributed to the batter's running or conduct.

A batter may even be given out Run out not attempting a run, just as if the ball were legal, except for the case that would be stumped were it not a no-ball, i.e. it is not out if the batter is not attempting a run and the wicket keeper puts the wicket down without the intervention of another fielder. The keeper can still run out the batter if they move to attempt a run.

Runs

[edit]When a no-ball is bowled, runs are awarded to the batting team. In Test cricket, One Day International cricket and T20 International cricket, the award is one run; in some domestic competitions, particularly one-day cricket competitions, the award is two runs. All such runs are scored as extras and are added to the batting team's total, but are not credited to the batter. For scoring, no-balls are considered to be the fault of the bowler (even if the infringement was committed by a fielder), and are recorded against the bowler's record in their bowling analysis.

In addition, if the batter hits the ball they may also take runs as normal, which are credited to them. If they do not hit it, byes or leg byes may be scored. Depending on the reason for the umpire's call of 'no-ball' (and hence its timing), the speed of the call, the speed of the delivery and the batter's reactions, the batter may be able to play a more aggressive shot at the delivery, safe in the knowledge that they cannot be dismissed by most methods.

Additional delivery

[edit]A no-ball does not count as one of the (usually six) deliveries in an over, and so an additional delivery must be bowled.

Free hit

[edit]If this competition mandates a free hit for the type of no-ball adjudged, the umpire will then signal that the additional delivery is a free hit by making circular movements in the air by extending one raised hand.

The free hit may also be ruled a no-ball or Wide, in which case the next ball is also a free hit, and so on. Once the bowler has bowled one legitimate 'free hit' ball, one ball is deemed to have been bowled towards the (usually six) legal balls required for one over, which then continues as normal.

Other effects

[edit]Dangerous and unfair play

[edit]As stated above, the effects of no-balls may be cumulative, and may reach beyond the completion of the game. Law 41 deals with dangerous and unfair play, and no-balls, in common with most transgressions of Law 41, may cause the umpires to initiate further sanctions. The bowler may be prevented from bowling for the rest of the innings, may face disciplinary action by bodies governing the game, and may be required to change the way they bowl. This is also the case for a bowler called under Law 21 for throwing. Sanctions now also apply for the deliberate bowling of front foot no-balls. Law 41 gives the umpires specific duties to ensure the safe conduct of the game in the case of unfair bowling.

Throughout cricket history, there have been occasions when the fielding team has needed to encourage the batting team to score freely and quickly, usually when enticing them not to settle for a draw, but sometimes to satisfy some competition rule. In some such cases, especially when the end of the match requires the completion of a specified number of overs, the fielding captain has encouraged the bowler to bowl deliberate no-balls by overstepping. Sometimes it has proved to be an ill-judged idea that risked both bringing the game into disrepute and losing the match, e.g.[12] From Oct 2017, this specific resort is no longer available, as a side-effect of the fact that deliberate overstepping will immediately be ruled "dangerous and unfair" by the umpire, but no-balls that breach other parts of the Law might still be concocted deliberately without being ruled unfair.

Umpire Decision Review System

[edit]Special complications arise in the professional game when technology is used to assist the umpires, and overturn a decision made on the field. Video review by the third umpire may reveal that a no-ball should have been called (especially for overstepping or a beamer) when the batter has been given out. If so, the ball is deemed to be dead from the moment of the 'dismissal event,' and any runs scored after that point (runs, byes or leg byes) will not count, but the batting team do get the no-ball penalty.[10] It is now customary for a batter given out to stand at the edge of the playing area and wait to see if the video may discover a no-ball, in which case they are reinstated. If the batsmen have crossed in running, the batsmen do not return to their original ends. Video review may also reveal that a no-ball should NOT have been called, in which case the ball becomes dead at the time of the on-field call.

Further consequences can occur in cases when the on-field decision has been overturned. For example, the batter is given out LBW, but the ball runs away off the pads, for what would be 4 leg-byes that win the game. The bowling side is thought to have won. The review adjudges the bowler to have overstepped. The batting team are awarded only a 1 run penalty for the no-ball, and an extra ball or free hit, but fail to score off it, and the bowling side still win, even though the batting side would have won if the umpire's decision had matched the video evidence discovered, although perhaps the fielding side might have tried harder to save the 4 leg byes had they known the match depended on it.[original research?] For such complications and other reasons, including concern to control the amount of time used in review, the ICC is experimenting with 'no-ball instant notification,' under which the umpire is immediately given the additional information to call no-ball while the ball is still live.[13]

If a 'Player Review' requested by the fielding side upholds a decision of 'Not Out', but a no-ball is discovered by the review, that review does not count as unsuccessful, and does not expend the reviews allocated to them.

Relationship with Penalty Runs

[edit]Unlike some breaches of Law 41, a no-ball only attracts the no-ball penalty (e.g. one run), there are no provisions in the Law or in common regulations for five penalty runs to be awarded to the batting team, and there are no incidents when five penalty runs are awarded that would require a no-ball to be called, although scenarios exist in which five penalty runs might be awarded when the ball is in play and would count in the over, were it not a no-ball for the reasons given here, for example: repeated damage to the wicket by the fielding team during a no-ball, or the ball hits a helmet on the ground during a no-ball.

History

[edit]The 1774 Laws of Cricket state "The bowler must deliver the Ball with one foot behind the Crease even with the wicket ... If he delivers the Ball with his hinder foot over the Bowling crease the Umpire shall call no Ball (sic), though she be struck or the player is Bowled out; which he shall do without being asked, and no Person shall have any right to ask him."

In the 1788 MCC code this became "The Bowler Shall deliver the Ball with one foot behind the Bowling Crease, and within the Return Crease...if the Bowler's foot is not behind the Bowling Crease, and within the return Crease, when he delivers the Ball, [the Umpires] must, unasked, call No Ball."

The early Laws do not define any consequence of No Ball. It is implied that, when called No Ball, the ball was not in play,[14] probably regarded as 'dead,' and the batting team did not benefit. No 'notch' was scored.

At some point before 1811, the batter was allowed to score runs from the no-ball, and was protected from being out, except by being run out. By this change the no-ball became a passage of play, and was probably intended to restrain the development of roundarm bowling. Further complicated modifications were made before 1817, then simplifications between 1825 and 1828 that expressly forbade roundarm.[15]

In 1829 the one run penalty was introduced for a no-ball when no run was scored otherwise.

The 1835 code legitimised roundarm bowling, and prevented overarm bowling by penalty of no-ball (see also 1835 English cricket season). The previous Laws did not disbar either, but had been interpreted variously by umpires reflecting custom and practice, at some cost to the careers of the bowling innovators. Further changes were made in 1845, and in 1864 bowlers were finally free to bowl overarm, enshrined in the pithy phrase "The ball must be bowled."

In 1835 The Umpire was required to call no-ball immediately the ball was delivered.

Under the 1884 code, a no-ball was called under Law 10 "The ball must be bowled; if thrown or jerked the umpire shall call No ball." and Law 11 "The bowler shall deliver the ball with one foot on the ground behind the bowling crease, and within the return crease, otherwise the umpire shall call No ball." Law 16 provided that "if no run be made one run shall be added to that score." Other detail was codified by Laws 13 (not to count in over), 16 (scoring runs and protection from being out), 17 (scoring of extras), 35 (failed attempt at run out before delivery), 48A (umpire call of no-ball) and 48B (umpire to make call immediately) [16]

1900s

[edit]A 1912 revision ruled that the batter could not be stumped from a no-ball. This caused difficulty until 1947 when the distinction between 'run out' and 'stumped' was clarified.

The 1947 code removed the requirement for the bowler's back foot to be on the ground behind the bowling crease at the moment of delivery. The change codified general umpiring practice, as the judgement had proved difficult to make.

Until 1963, a no-ball was called when the bowler's back foot landed over the bowling crease (which is why the bowling crease was so called), exactly as in 1774. But it was felt that the tallest fast bowlers, able to bowl legally with their front foot well over the popping crease, were gaining too great an advantage. Bowlers also became skilled in dragging their back foot. The change in the Law led to an increase in no-balls: in the 1962–63 series between Australia and England there were 5 no-balls; in the series between the two teams three years later there were 25.

Until 1957, there was no limitation on fielders behind square on the leg side. The change is often attributed to the desire to thwart bodyline, but the Bodyline Controversy was in 1933. The conservative instincts of cricket, and the intervention of World War II, may have been factors in the delay, but as the bodyline article explains, there was more than one reason for the change. Initially a no-ball under "Experimental Note 3 to Law 44" was confined to first class cricket (including all international cricket) and became part of the Laws of Cricket as Law 41.2 in 1980.

In 1980, the main codification of no-ball Law became Law 24, with no-balls also called under Law 40 (the wicket-keeper), Law 41 (the fielder) and Law 42 (Unfair Play). The new code made encroachment onto the wicket by the wicket-keeper and fielders a no-ball. In old film footage, for example of Underwood's Test in 1968, close fielders can be seen in positions that would nowadays cause a no-ball to be called [2]. Previously the fielder could stand anywhere as long as they were still, did not distract the batter, nor interfere with their right to play the ball. Umpires would conventionally intervene if a player's shadow fell on the pitch, which is still widely treated as a distraction, but not inherently a no-ball.

Prior to 1980, if the wicket keeper took the ball in front of the stumps the umpire would turn down any appeal for a stumping, but would not have called no-ball.

Since the mid 1980s, no-balls have been accounted against the bowler in calculating their statistics [17]

The 1947 code explicitly provided, in Law 26 Note 4, that it was not a no-ball if the bowler broke the bowler's end wicket. No such explicit words appear in the 1980 code.

2000s

[edit]From 30 April 2013 (ICC playing regulation) and 1 Oct 2013 (Law) a no-ball results when the bowler breaks the non-striker's wicket during the act of delivery. For a short period prior to this, umpires had adopted the convention of calling 'dead ball' when this happened. See Steven Finn for origins of the change.[18][19]

The year 2000 Code was a major change, and added the no-ball sanction for waist-high fast beamers, balls bouncing over head height, and balls bouncing more than twice or coming to rest in front of the striker. It also removed the judgement of intent to intimidate on fast short pitched bowling.

Prior to 2000, one no-ball run penalty was only scored if no runs were scored otherwise.

From October 2007 all foot-fault no-balls bowled in One Day Internationals resulted in a free hit.[20]

From 5 July 2015 all no-balls bowled in either One Day Internationals or Twenty20 Internationals resulted in a free hit.[21]

From 2013 some competitions outlawed the double-bounce ball in order to thwart negative developments in bowling [22] [23] [24]

The change to a maximum of one single bounce became Law in all forms of cricket in the Oct 2017 Law code, which also outlawed a ball that bounced off the pitch even if it then became playable.

Between 2000 and 2017, a beamer was judged a no-ball under the Laws of Cricket if it passed the batter above waist height, when delivered by a fast bowler, or above the shoulder when delivered by a slow bowler. The professional regulations did not tolerate the slow shoulder-high beamer. The Oct 2017 changes set the limit for beamers in all cricket at waist height, regardless of delivery speed.

The Oct 2017 Law code changes also removed the need for repetition before calling a no-ball for dangerous short-pitched bowling (bouncers), introduced the judgement of repetition in head-high bouncers as unfair, and treated a deliberate front foot no-ball as 'dangerous or unfair,' with immediate sanctions as for a deliberate beamer. The new code reduced the warning for throwing to one first and final, instead of the two warnings that had existed since 2000. An explicit penalty for underarm bowling was stipulated, although such bowling was deemed a no-ball in 2000. Interception of the ball by a fielder before reaching the batter became an explicit no-ball.

Laws were also renumbered so that no-balls are now called under Law 21 (was 24), with no-balls also called under Law 27 - the Wicket-Keeper (was 40), Law 28 - the Fielder (was 41) and Law 41 - Unfair Play (was 42).

Prior to 2017 any byes and leg byes taken from a no-ball were scored as no-ball extras, but are now scored as bye and leg bye extras.

From April 2019 any beamer is unfair and therefore a no-ball, but the Umpire can now judge that a particular beamer is not also dangerous, and does not warrant a warning or suspension. The 2019 code defines what 'waist' means for the first time.[3]

From 2022, Law 25.8 asserts the striker's right to play the ball, but within limits to ensure they do not risk contact with the fielders. Thus any delivery that requires the striker to leave the pitch is immediately judged and called a dead ball, and a no-ball awarded in recompense. [25] The new no-ball case is grouped together with "ball coming to rest in front of striker's wicket" under existing no-ball Law 21.8.

Also from 2022 the rarely-exercised provision for the bowler throwing ball towards striker's wicket before entering the "delivery stride" in an attempt to run out a striker is no longer a no-ball: if it is attempted the umpire should now just call dead ball. The old Law was said to be a source of confusion.[25]

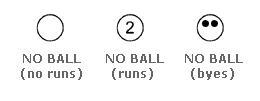

Scoring notation

[edit]The conventional notation for a no-ball is a circle, and it can be abbreviated "nb". If the batter hits the ball and takes runs, a boundary 4 or boundary 6 off the delivery, then the runs are marked inside the circle. In practice it is easier to write down the number then encircle it.

If the batsmen run byes following a no-ball, or the ball runs to the boundary for 4 byes, each bye taken is marked with a dot inside the circle. Again it is easier to encircle the dots.

Capitalisation convention and grammar

[edit]Both the MCC Laws of Cricket [26] and the ICC Playing Conditions [27] use the capitalisation convention "No ball" throughout, though most major news sources prefer "no-ball", which is standard English usage.[28]

The grammar is significant in the history and development of the game as outlined above: initially a no Ball is a non-event: when the Umpire calls "no Ball" they mean nothing has happened - there has been no Ball. It would have been inexplicable to hyphenate the phrase, or capitalise the "No" rather than the "Ball," since there is initially no event called "No ball," simply the absence of any Ball.

"No ball" evolved as a concept and sanction in the Law to prevent disruptive late Georgian innovation. A "No ball" is no longer just the absence of a "Ball," it is the occurrence of an unacceptable practice for which legislation and consequence is provided. Eventually a "No ball" became an active passage of play in which runs are scored and batsmen can even be out.[15]

The modern usage, "no-ball" as a compound phrase arises in part because finally a no-ball is a commonplace event in its own right, one that leads occasionally even to international diplomatic flurries or even imprisonment. It is used both as a noun-phrase and a verb-phrase, "The Umpire will no-ball you ..."

See also

[edit]- Pakistan cricket spot-fixing scandal, in which no-balls were deliberately bowled as part of a betting scam.

- Balk, similar concept in baseball.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Throughout this page, the common usage "no-ball" is preferred to the convention "No ball" used in the Laws of Cricket. See the section "Capitalisation convention and grammar" for further explanation

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "Law 21 – No ball". MCC. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Law 41 – Unfair play". MCC. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ a b "2017 code 2nd Edition" (PDF). MCC. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Law 27 – The wicket-keeper". MCC. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Law 28 – The fielder". MCC. Retrieved 29 September 2017.

- ^ "3rd ODI (D/N), The Oval, September 13, 2023, New Zealand tour of England". CricInfo.

- ^ "ICC Men's Twenty20 International Playing Conditions" (PDF). International Cricket Council.

- ^ "IPLT20 match playing conditions 42 Law 42 Fair and Unfair Play". BCCI. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013.

- ^ "ICC Men's One Day International Playing Conditions" (PDF). International Cricket Council.

- ^ a b "ICC Men's Test Match Playing Conditions" (PDF). International Cricket Council.

- ^ Marylebone Cricket Club, Tom Smith's Cricket Umpiring and Scoring, Marylebone Cricket Club, 2019

- ^ .[1]

- ^ "Association of Cricket Officials, p.33 Association of Cricket Officials Magazine, ACO, Issue 27 Winter 2016"

- ^ Trevor Bailey, A History of Cricket, George Allen & Unwin, 1979

- ^ a b R.S. Rait Kerr, The Laws of Cricket Their History and Growth, Longmans, 1950

- ^ "Laws of Cricket 1884 Code". ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Influence of wides and no balls on Test bowler averages". ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "MCC Introduces New No Ball Law". Marylebone Cricket Club.

- ^ "ICC adopts no-ball Law after Finn problem". CricInfo.

- ^ "Clarification to free-hit regulation in ODIs". ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "Bowlers benefit from ODI rule changes". ESPN Cricinfo. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ ""IPLT20 Match Playing Conditions Law 24"". IPL, BCCI. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- ^ "2013 Regulations and Playing Conditions – first-class County The LV= County Championship, Other first-class Matches and Non-first-class MCC University Matches against Counties" (PDF). England and Wales Cricket Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ "ECB outlaws Warwickshire's idea to start bowling double-bouncing deliveries". Telegraph Media Group Limited.

- ^ a b "Law Changes 2022" (PDF). MCC. Retrieved 12 December 2022.

- ^ "MCC Law". Marylebone Cricket Club.

- ^ "ICC Men's Test Match Playing Conditions" (PDF). icc-cricket.com. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- ^ "Oxford English Dictionary". Oxford University Press.